The Coen brothers' version of True Grit opens with a slow track in on a man lying dead on a street in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in the 1870s. In a voice-over, an older woman recounts the details of the man's death. He was her father, and was shot down in cold blood by his hired hand, who then fled into the Choctaw Nation, beyond the reach of Arkansas law. She, at the age of fourteen, decided to go after the man and bring him to justice. Snow falls over the body, and snow will be a recurring visual motif in the film that follows. It will become a quiet emblem of grace in a tale of violence and revenge.

The slow tracking shot and the narration and the gentle snowfall ask us to settle back and concentrate . . . on a story that will take its time in the telling, as most good stories do. Joel and Ethan Coen are asserting that they have a real story to tell, a story worth hearing, and this assertion comes as shock in the context of most movies of our time, which assault us furiously with fast cutting and loud sounds, trying to get our attention by crude means, usually to hide the fact that that there will be no story on offer — just a series of sensations.

Everything about this film asks the audience to step forward towards it, to pay attention, to look for a personal reaction instead of a reaction prefabricated by the filmmakers. Those whose perceptions have been dulled by the sensory assaults of modern films, or whose imaginations have been crippled by stories which are not really stories but just a collection of incidents, may find themselves a bit put out. The rest will find themselves embarked on a great adventure — not just as spectators but as participants.

Visually, the film is structured around shots — beautiful images of deep spaces that we can enter into imaginatively. This is extremely rare in modern films, which are generally structured around rapid sequences of shots, none of which is interesting or seductive in itself — it's only the fake excitement of the cutting that we're meant to respond to. This works the way the spiel of a three-card monte dealer works — to distract us from the flim-flam he's trying to put over on us with his sleight-of-hand.

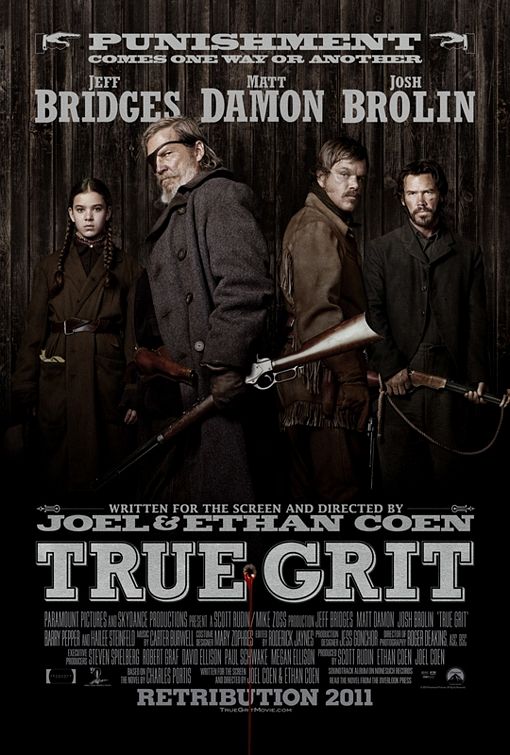

The performances of the actors make no explicit appeals to our judgment or affections. Jeff Bridges, as Rooster Cogburn, snarls and mumbles his lines as though he doesn't much care if he's understood — but it's Cogburn who doesn't care, not Bridges. Bridges is simply thoroughly absorbed in Cogburn.

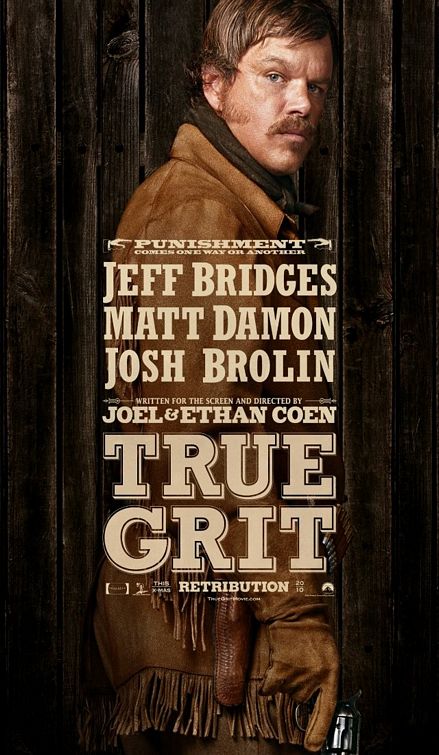

Matt Damon, playing a Texas Ranger named La Boeuf who's a bit of a dolt, never puts quotes around his bombast or his insecurity, to let us know that he, Damon, is not that sort of fellow. He puts the fellow before us as he is, with absolute conviction, and this makes for a spectacular pay-off when La Boeuf proves his mettle at the film's climax. Having allowed us to take his faults seriously, Damon also allows us to take his redemption seriously.

Hailee Steinfeld as Mattie also makes no direct appeal to our goodwill. Mattie is a pill in many ways, a plucky but very cold and judgmental little girl. Her need and fear are never emphasized, her love for Cogburn is never articulated or sentimentalized in any way. We are given the space to feel her emotional odyssey because we haven't been prompted to read it as such, haven't had our noses rubbed in it.

Almost every moment in the film that might have been milked for an obvious audience response — like Cogburn's heroic ride against the four bad men — is all but thrown away, in the sense that we aren't provided with that extra note of emphasis reminding us of the import of what we're watching, that little pause in which we're meant to cheer. The tale proceeds as if it were happening without us, and that, by the paradox of storytelling, draws us deeper into it. It's a tale that blossoms and clobbers us over the head only at the end of it, perhaps only after we've left the theater, resonating like a real experience of real things.

If you find, after seeing the film, that you love Mattie Ross and Reuben Cogburn and Ranger La Boeuf, it's not the result of a story committee in Hollywood telling you that they're lovable — it's the result of something that has happened in your own heart.

It takes a lot of skill to tell a story this way. In the modern age, it takes even more courage. Hollywood hates and despises its audience — believes it brings nothing to a film, except perhaps a recognition of the name of the property that's been adapted to the screen, and certainly not a human heart.

The Coen brothers, in True Grit, imagined an audience made up of real people, with real emotions, real moral and spiritual concerns — an audience that would bring as much to the table as their film brought, ready for a conversation about serious and wonderful things.

As it turns out, there was such an audience out there, ready for such a conversation — which is why True Grit became a surprise hit over the recent holidays. That audience is still there. It is still ready. You can be sure, too, that Hollywood still hates and despises it, which is why, increasingly, audiences hate and despise most of what Hollywood has to offer. Movie attendance in 2010 was the lowest it's been in fifteen years.

It's easy to see where this trail is heading — and it's not Hollywood's way. The major studios still have a practical veto power over what films audiences will see — but only in the short term. In the long term, audiences will have an even more efficient veto power over Hollywood, and everything that Hollywood represents.