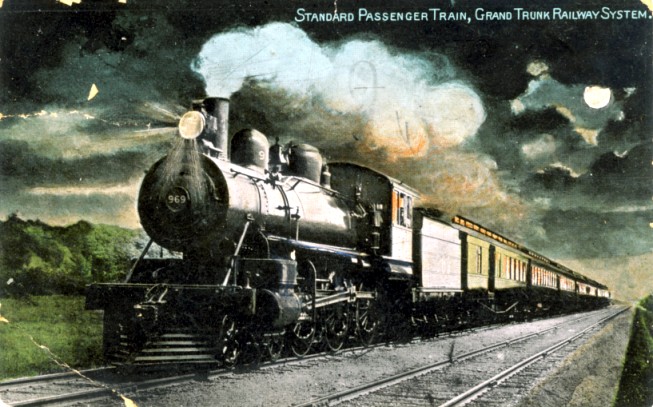

The Duquesne Line was a train service between Pittsburgh and New York City. Absorbed by Amtrak in 1971 and renamed, it is now a kind of ghost line, so when Dylan sings “Listen to that Duquesne whistle blowing” he’s asking us to listen to a train moving through the American past.

The driving beat of the song makes it clear, however, that the ghost train is still operational and running at full steam — in Dylan’s world, where the past and the present intermingle, it can still get you where you’re going, or bring your lady to town.

It approaches slowly, from a distance, in the instrumental opening to the song — a jaunty vamp with a quaint old-timey feel — then suddenly it’s right on top of you as it kicks into a hard-driving rock arrangement with an insistent pulse. The momentum of the arrangement never falters — the feel of it is exhilarating, inspiring.

The train takes you back to a sweeter time, a time of youthful simplicity. “You’re smiling through the fence at me,” Dylan sings, “just like you always smiled before.” And, “I wonder if that old oak tree’s still standing, the old oak tree, the one we used to climb.” If it’s still there, the Duquesne train will take you to it.

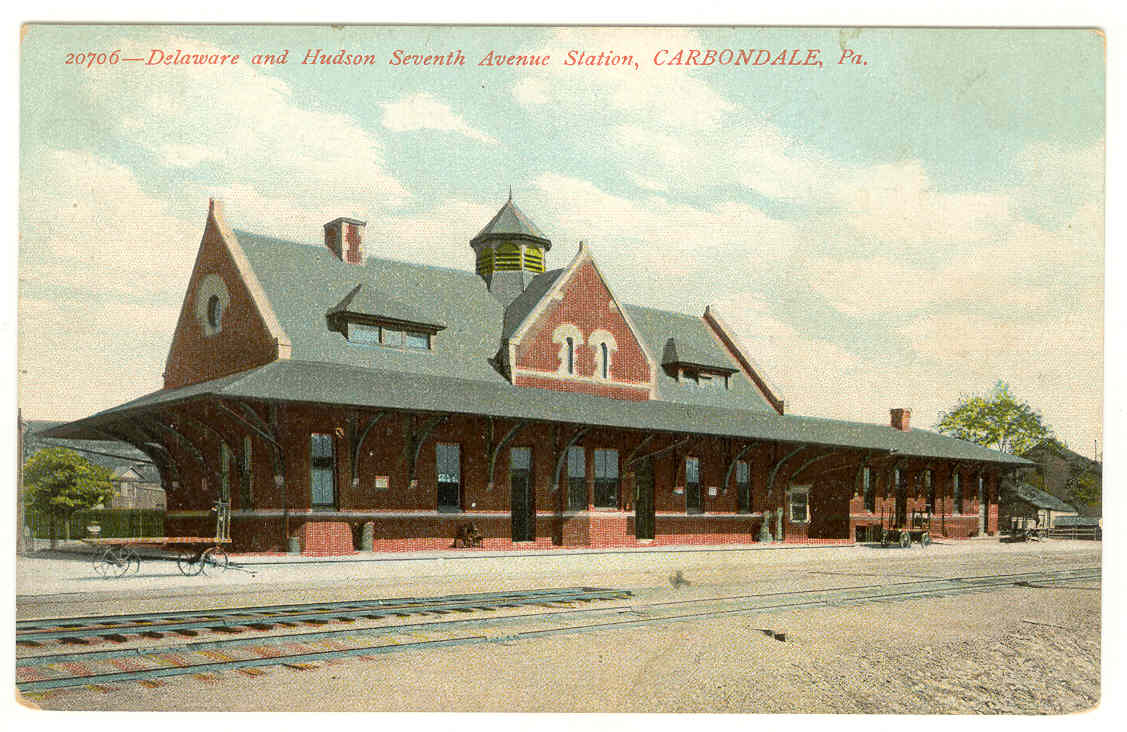

The line “I’m going to stop in Carbondale, and keep on going” makes me laugh for some reason. It’s like the singer is saying, “Yeah, Carbondale, man — but not for too long. Because, you know, there’s not a lot to do in Carbondale.”

This train will take you back to a time of faith as well. “I hear a sweet voice gently calling — must be the Mother Of Our Lord.” Must be — on this line. The whistle of the train sounds as though it’s going to “sweep my world away”, but also as though it’s going to “blow my blues away”. It sounds as though “it’s on its final run” — “blowing like she ain’t gonna blow no more” — but it’s also “blowing like it never blowed before” and “blowing like my woman’s on board.” Finally it sounds as though “it’s blowing right on time.”

“The lights of my native land are glowing,” Dylan sings. “I wonder if they’ll know me next time round.” It’s easy to fall in love with particular phases of Dylan’s art, and never want him to change. The folkies did this and were appalled when he went electric. Fans of the great Sixties albums (myself included) had a hard time coping with his explicit Christian songs. He has no patience for this insistence on stylistic or conceptual stasis.

Tempest is a new departure, too, with lyrics that are denser, more disturbing than any Dylan has written before. The tone of a song can shift from line to line, the lines themselves embody multiple and contradictory meanings simultaneously. It’s an unstable work of art, as though it’s composed of fissionable material. It has the power to unleash uncontrollable chain reactions of association and emotion without fair warning.

The Duquesne whistle identifies a mystery train, all right. It calls us cheerfully into new territory, but warns us that things will be odd there, that nothing will be quite what it seems, that the past will be alive there but not always comforting, that the end of days might be just around the next bend.

Still, it’s hard to resist the promise of that whistle, the driving beat of those ghost-train wheels . . .

Back to the Tempest track list page.