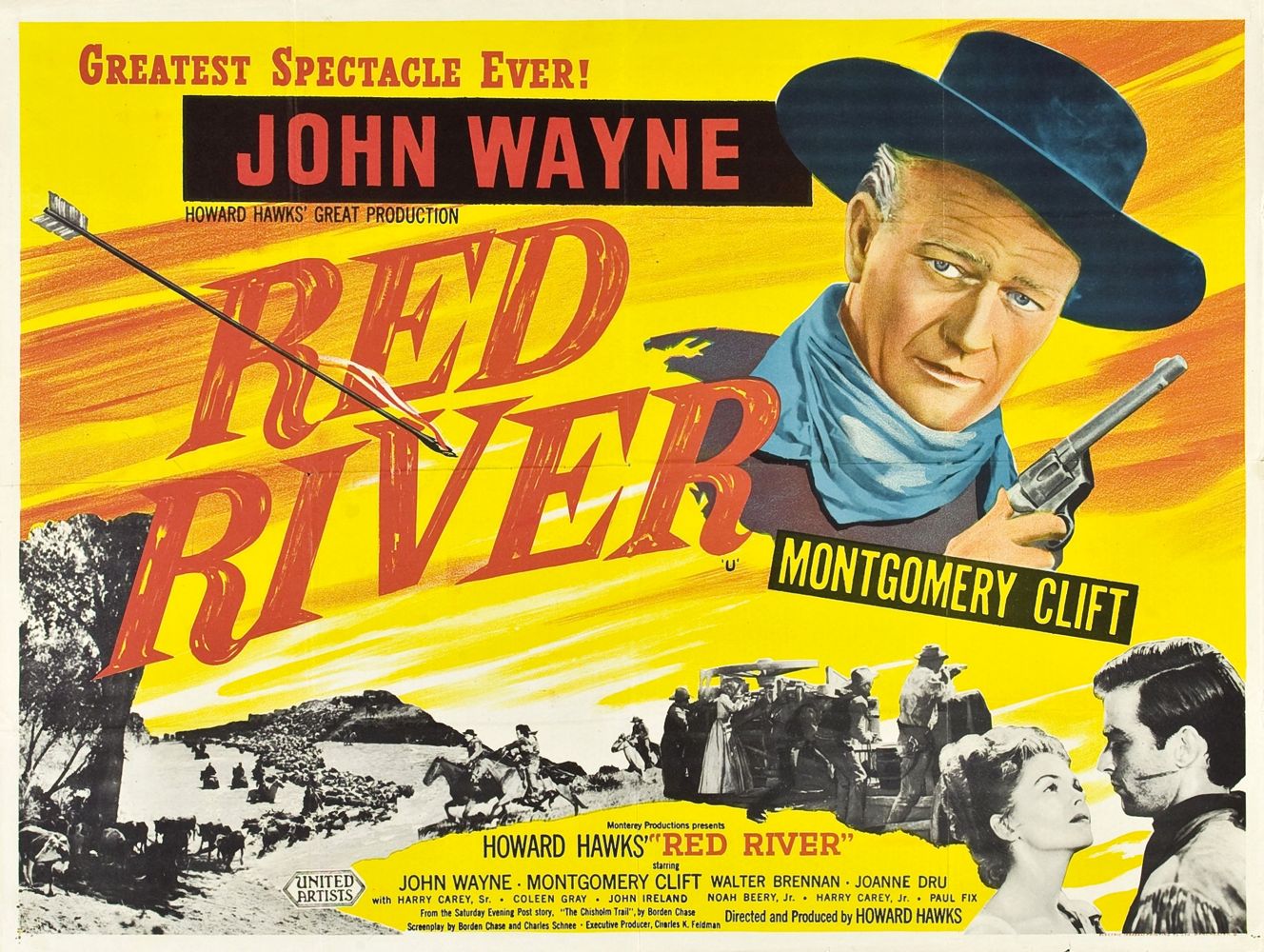

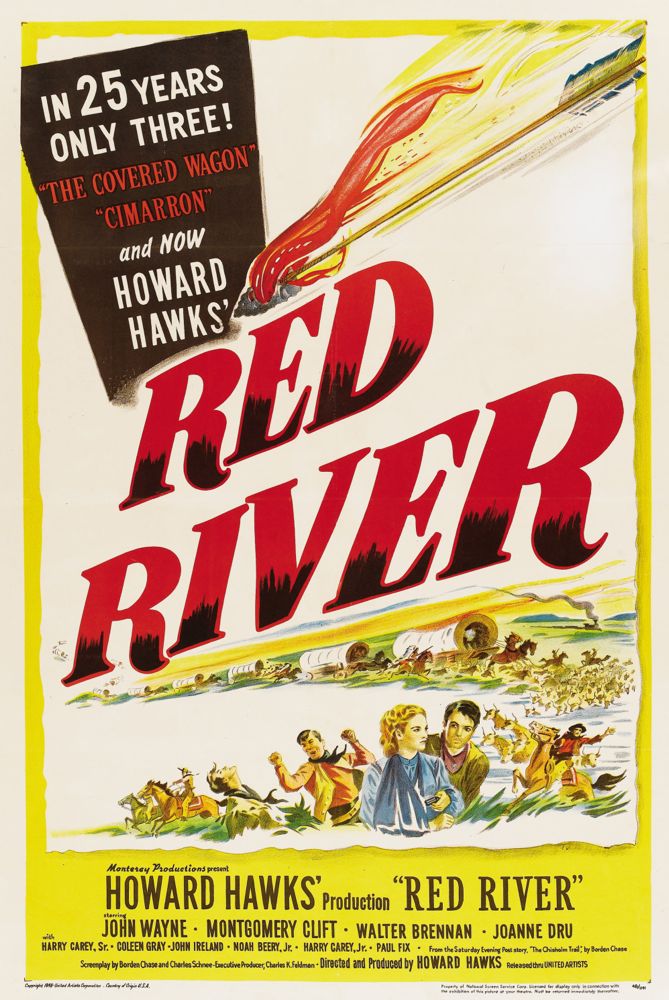

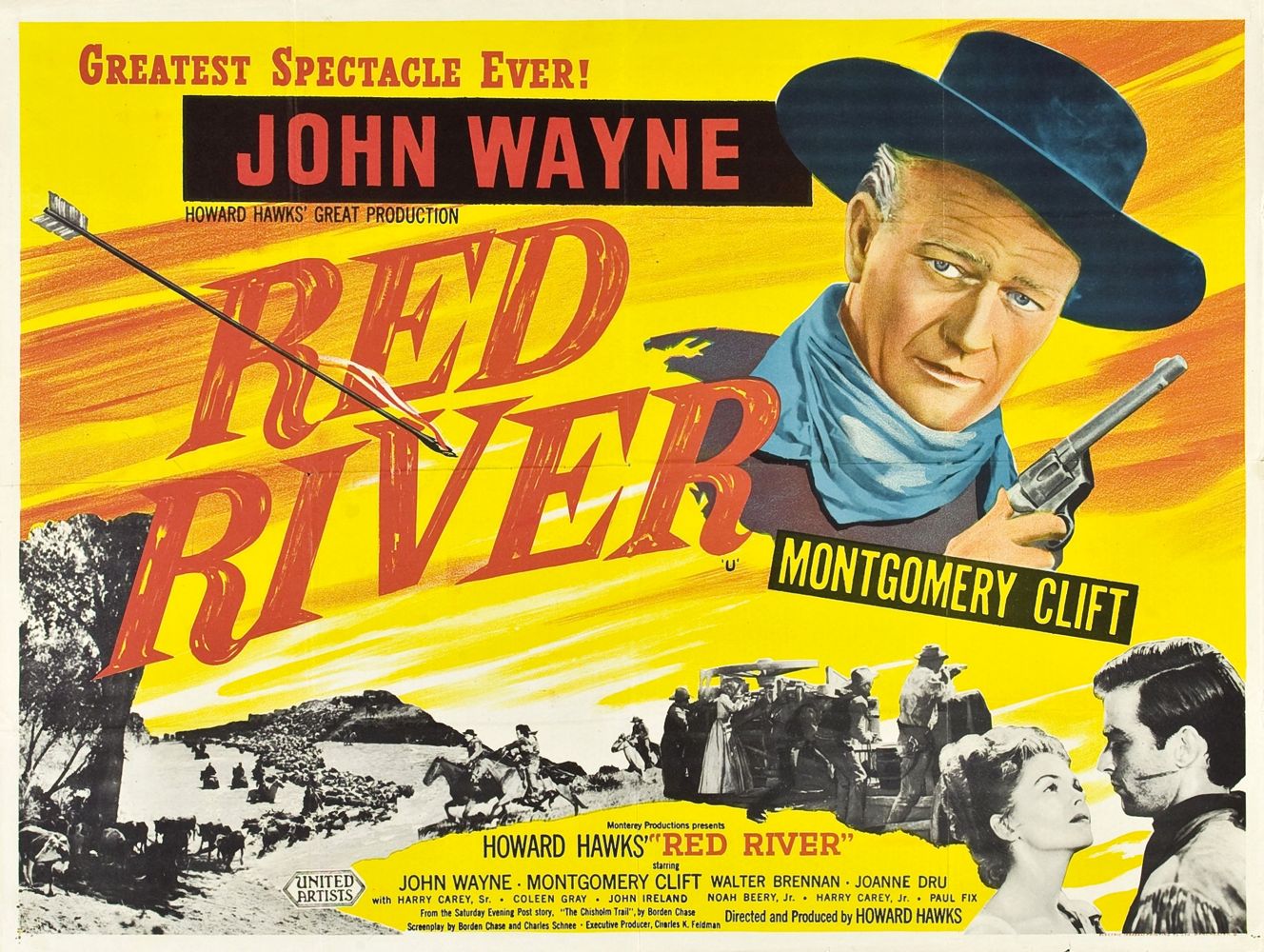

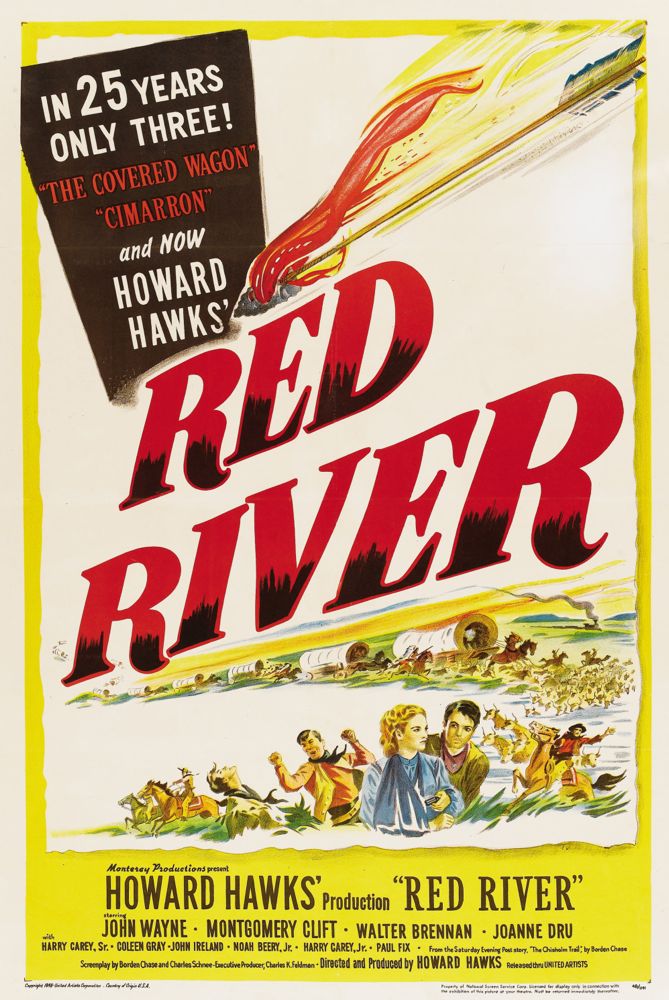

A lot of folks reckon Red River to be one of the greatest Westerns ever made but I myself don’t see it that way. It’s a damn good Western, and a fine entertainment, but to me there’s something just a little off about it.

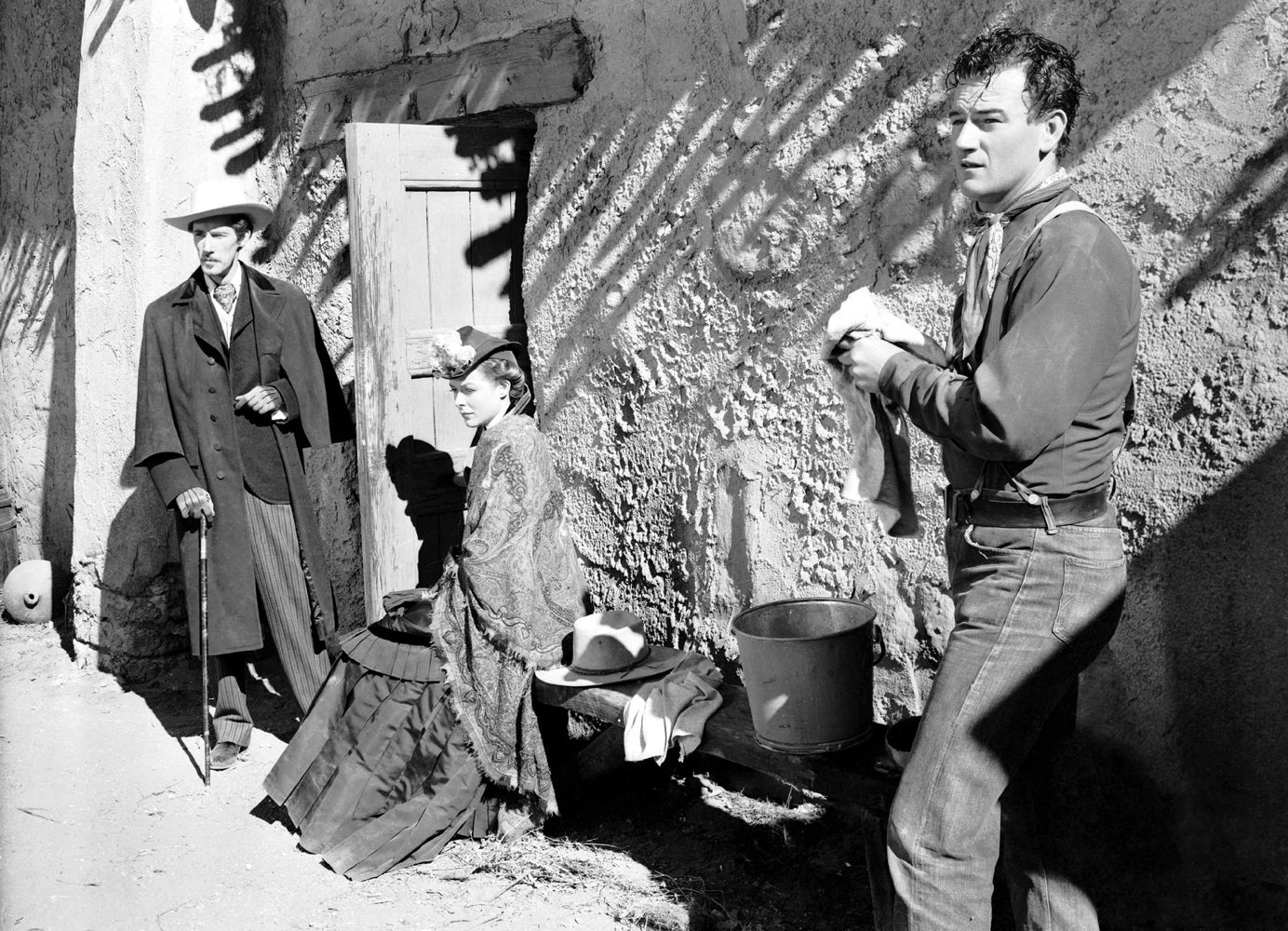

The outdoor scenes were all shot in southern Arizona and are spectacularly good. The crossing of the cattle over the Red River is as impressive as any river crossing in any Western. Throughout the film John Wayne gives one of his very best performances, ably supported by Montgomery Clift, Walter Brennan and Joanne Dru.

Its first 45 minutes are as good as the first 45 minutes of any Western, but the film seems to wander off the trail a bit after that, starting with the sequence of the night stampede.

[Spoilers below]

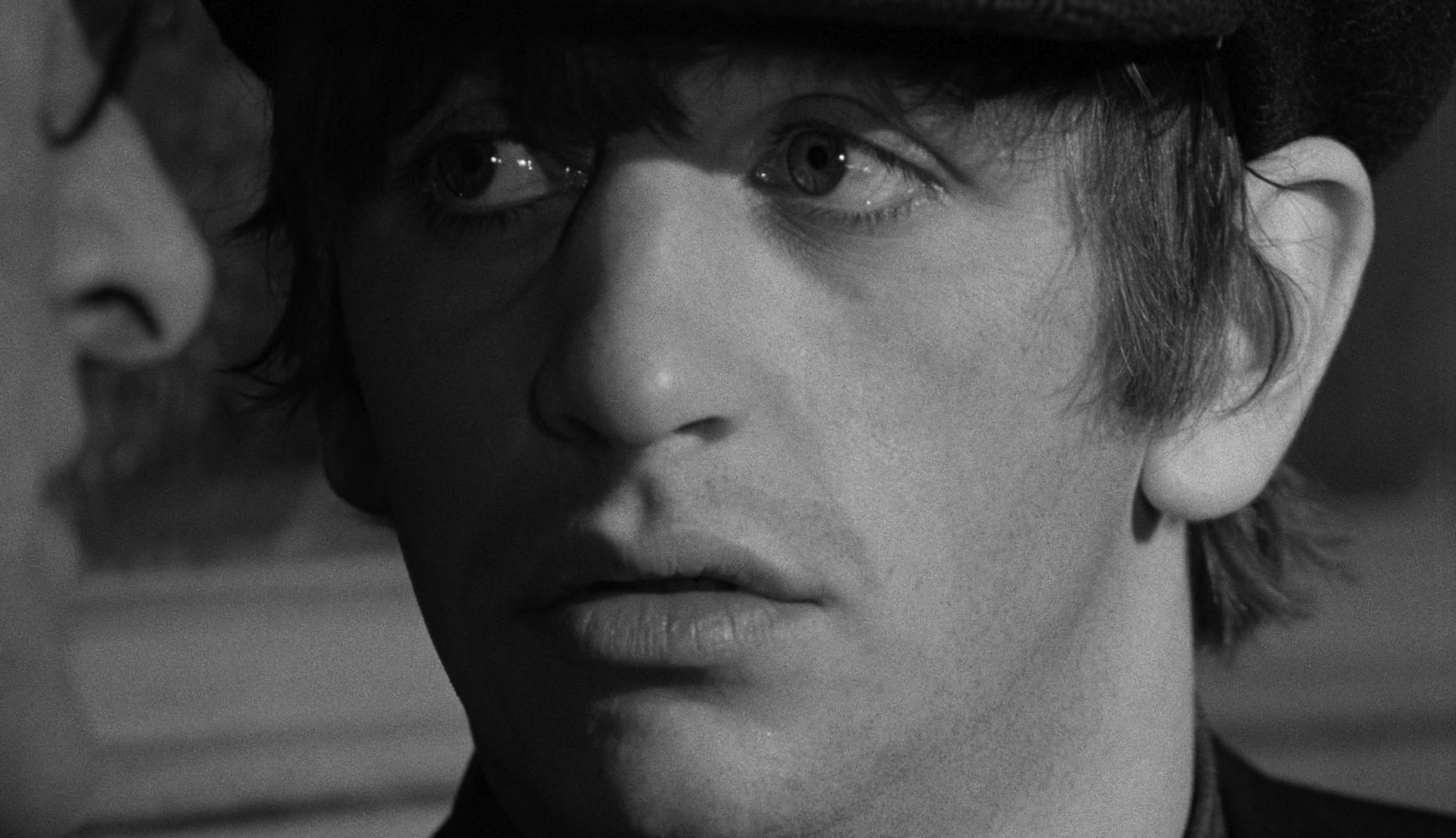

Having Latimer, well played by Harry Carey, Jr. (above), talk about his wife and his hopes and his dreams moments before getting killed in the stampede comes across as artificial. The stampede itself, though it incorporates some stunning location footage of rampaging longhorns, is interrupted once too often by inserts shot back at the studio on a sound stage.

The sequence has emotional power but it feels like an interpolation and too obviously manipulative. Hawks generally got at sentimental effects in less direct ways. More importantly, it feels like a departure from the easy and natural way the film establishes its characters and their conflicts in the first 45 minutes, with crackling dialogue and inventive exposition that never plays as exposition.

Hawks being Hawks, a master storyteller, the stampede has a legitimate function in the overall structure of the tale, motivating John Wayne’s character, Tom Dunson, in an understandable way, to commit his first suspect act as the boss of the trail drive, coming very close to killing the hapless cowboy who caused the catastrophe.

This line of development gets more and more intense after the stampede, Dunson more and more unreasonable and unhinged. We proceed to the triumphal and visually masterful crossing of the cattle over the Red — a superb piece of filmmaking — only to find that it hasn’t settled Dunson down at all.

A final confrontation with his adopted son Matthew Garth, played by Clift, causes Garth to mutiny and take control of the drive, exiling Dunson, who promises to come back and kill him. This is the core of the movie — revealed now to be a version of Mutiny On the Bounty on horseback.

At this point, it ran into the same problem Mutiny On the Bountry ran into dramatically. The tension between Christian and Bligh, having reached its climax in the mutiny, essentially ends and the tale bifurcates. We see what happens to Christian, we see what happens to Bligh, but the personal face-to-face conflict between the two men, the engine of the drama, is over.

Hawks was wise enough to bring his Christian and Bligh together at the end for a final showdown, but the narrative mechanism he used to arrange this was clumsy. Basically it involved the late introduction of a new character, Tess Millay, played by Joanne Dru. Garth rescues her from a wagon train under attack by Indians, then leaves her, whereupon she falls in with Dunson and becomes a kind of mediator between the two men, finally stopping their duel to the death at the end of the film.

It makes for some interesting interactions between the characters, but feels a little jury-rigged as a plot development. The film was based on a Saturday Evening Post story by Borden Chase, who wrote the first draft of the screenplay. Chase thought the heart of the tale lay in the triangle between Dunson, Garth and Millay. Hawks wanted it to lie in the spectacle and historical consequence of the first major cattle drive to a rail-head in Kansas, so he hired Charles Schnee to rewrite the script with that in mind.

He and Schnee never really solved the problem of how to integrate the two parts of the movie into a whole. Two thirds of it is the epic tale of a cattle drive with a Mutiny On the Bounty structure, the last third concentrates on an intriguing emotional triangle between three characters. Hawks acknowledged this in later years, saying he was never happy with the ending of the film, but he blamed it on Schnee and on Dru, a last-minute replacement for another actress — he said Dru simply didn’t know how to play the role correctly.

In fact, Dru (above) is wonderful in the film, and no actor giving any kind of a performance could have resolved the split nature of the narrative. The ending is satisfying enough, if a little perfunctory — Millay simply tells Dunson and Garth to stop fighting because they love each other, so they stop fighting.

The film remains a fine entertainment, because each section of it is involving and well executed, but it doesn’t have the driving through-line, the structural cohesion, of a first-rate film, a first-rate Western. Surely some way could have been found to introduce Millay earlier and more naturally into the narrative — Hawks and his writers simply didn’t take the trouble to do it.

Audiences didn’t seem to mind — the film was a huge hit and is now considered a classic, though I myself don’t think it measures up to Hawks’s other important Western, Rio Bravo, a less ambitious film in some ways but in my opinion a flat-out masterpiece.

Click on the images to enlarge.