A look back at Lloyd in 2012, and Thanksgiving with Jae. On the town.

Dark Harbor, Wilmington, 2am

“Dark Harbor” was written in the house that the Fonvielles owned in the village of Dark Harbor, Maine, on the island of Islesboro in upper Penobscot Bay. Originally built as the guest house of Ruth Draper, a famous performing artist, a monologuist, in the 1920s, the house, a classic “summer cottage,” had a long lawn running down to a small dock. It was a lovely setting.

Hugh writes: “I was upstairs in a bedroom fooling around with my guitar and a strange melody and chords emerged. I refined them and went downstairs to show Lloyd. Meanwhile, he had been sitting in the living room writing a poem. Astoundingly, the music and the words fit together and the song was born. I¹m almost positive the year was 1970, summertime.”

This version was recorded in the deserted lobby of Hilton Garden Inn about 2am, after the day’s service and the evening’s gathering with its eating and drinking and talking and singing.

Hugh and I were the last to retire.

But, Lloyd, as would please him, had the last words.

— Cotty Chubb

©1973, Lloyd Fonvielle & Hugh McCarten

(If you can’t get the song to play in this post, you can find it here.)

Remarks at the service by Rev. Paul F. M. Zahl

What is the meaning of an individual human life? What counts, or lasts, or is enduring about it?

Out of the complete originality of Lloyd Fonvielle, what “stands”?

His aspiration to love and be loved. This is probably the bottom line of any person’s life..

Lloyd’s aspirations concerning love – his ruminations on the nature, or possibility, of love – animated his work, and all in a unique, ever-changing but also continuous-with-itself package.

Lloyd’s writings on photography, especially concerning William Eggleston; his writings on ballet and George Balanchine – and remembering especially Lloyd’s remarkable friendship with Lincoln Kirstein; Lloyd’s script for The Bride; elements in Lords of Discipline; Gotham (!); Circus, for sure; many of Lloyd’s Western short stories, his “noirs”, right through to the last one, Black Pearl..

Many if not most of these are ruminations on love and its sometime impossibility, and its devoutly to-be-hoped-for possibility.

Lloyd was extremely interested in the mercurial and at times hopefully enduring relations between men and women.

Lloyd also loved his family very much, and they were always a very large part of his life. Mary and I often wished that Lloyd had been able to have children. As it was, Lloyd had a special heart for his nephews and nieces, each one of them!

I think everyone here would agree that Lloyd was lost to us too soon.

Here is the second of two points in this short memorial sermon:

Where is Lloyd now?

That’s a big one. To me, it is the biggest one.

Whatever you think about the answer – I mean, whatever you think the answer to that question might be – every person has to engage the question somehow, simply because we all die. As Lloyd has died.

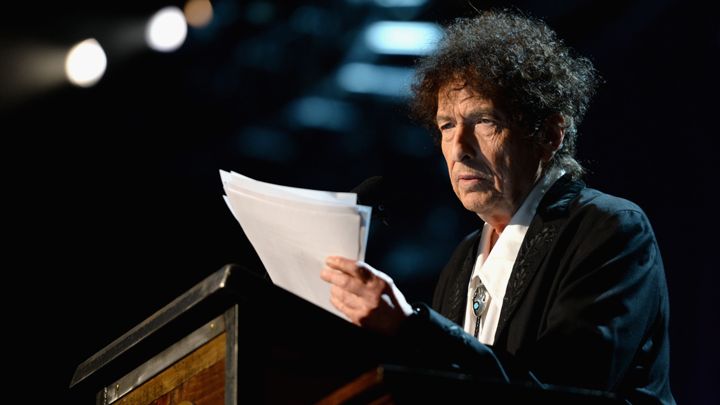

Lloyd has pre-deceased every one of us who is here. (I was always sure that Bob Dylan would pre-decease Lloyd, by the way, but it didn’t turn out that way.) Lloyd now knows something, or has found out something, that none of us here today can answer with certainty. Lloyd now knows, or has found out, something that Bob Dylan doesn’t know.

Here is my simple answer to the question of where Lloyd is:

Lloyd is with the God of Love and Mercy.

Lloyd remained a Christian throughout his life, right up to the very end of it. He and I talked on the phone about faith and God and the person he called ‘Rabbi Jeshua bar Joseph’ only three days before he died. Why did Lloyd remain religious? (He detested most human representations of Christianity.) For one basic reason: Bob Dylan! Just kidding.

No, but really:

Lloyd was drawn to Christianity because of the human life and actings-out-of-compassion that Lloyd saw in that person with the long Hebrew name. That’s just a fact, about Lloyd.

So where is Lloyd today?

He is with that kind of God, within that kind of Reality.

LWF Memorial Service — September 19th, 2015

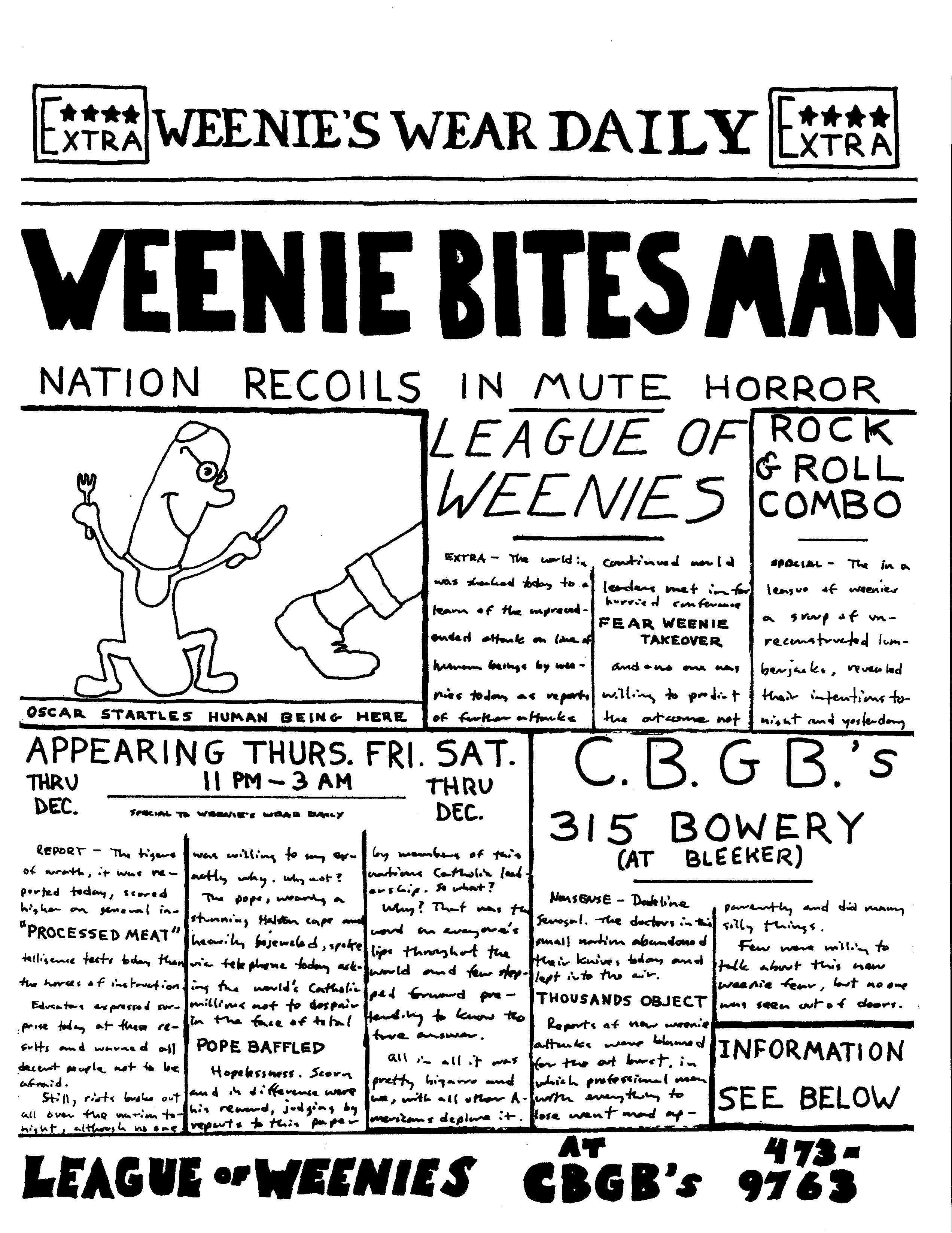

Weenie’s Wear Daily

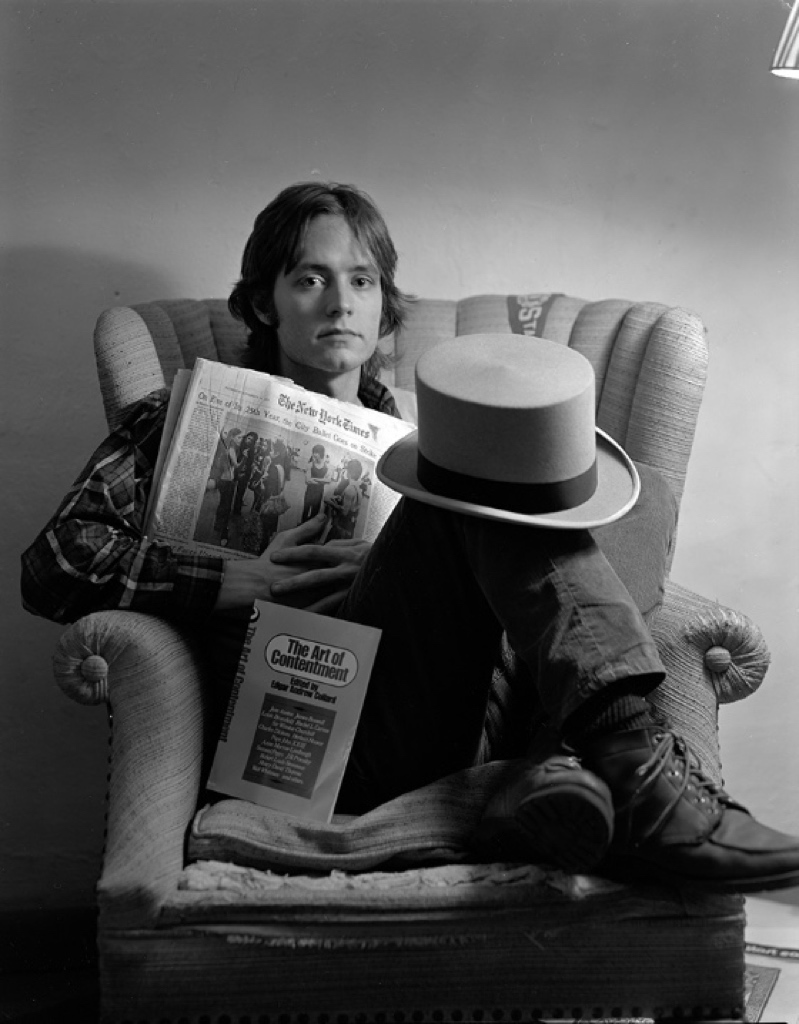

New York in the early 70s. Hugh McCarten, one of Lloyd’s best friends since they met at boarding school in 8th grade, was the piano player and de facto band leader of The League of Weenies.

Lloyd created this flyer to celebrate their gig at the not yet celebrated club on the Bowery, CBGB & OMFUG, usually known as CBGB’s. Talking Heads wouldn’t play there for another two years.

And, just because, here are a couple of Weenies tunes.

“Malibu Moon” (Fruchtman/Allen) — recorded live at The Ballroom (1975)

“What The Funk” (Fruchtman) — recorded at 55 West 19th St., NYC, 1974.

The League of Weenies (Oscar Fruchtman, rhythm guitar & lead vocals; Ed “Woody” Allen, guitar & vocals; Hugh McCarten, piano & vocals; David Drucker, bass; Dave Pentecost, drums) were nearly the last signing of the legendary John Hammond at Columbia Records, but that’s a story for another day.

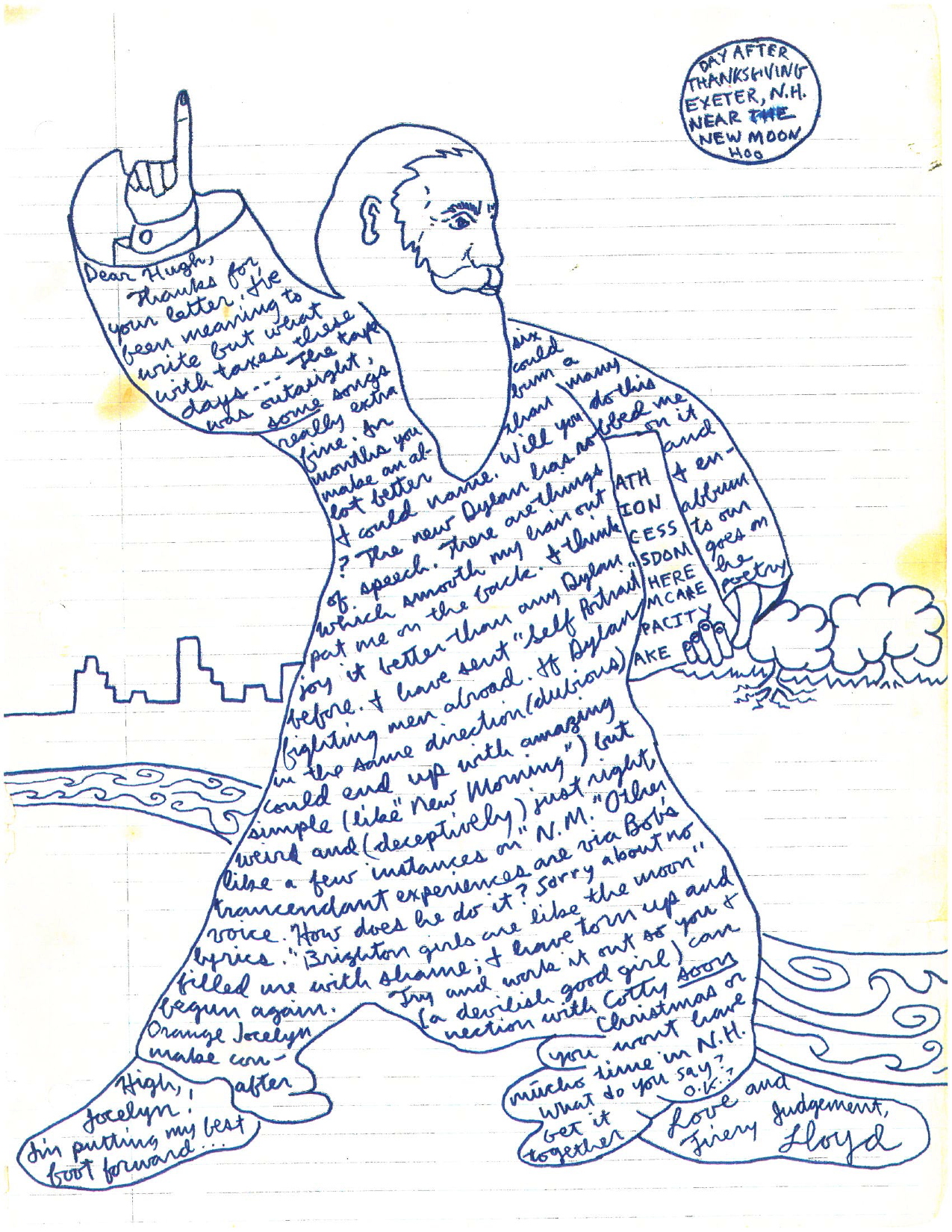

Some Thoughts on New Morning (1970)

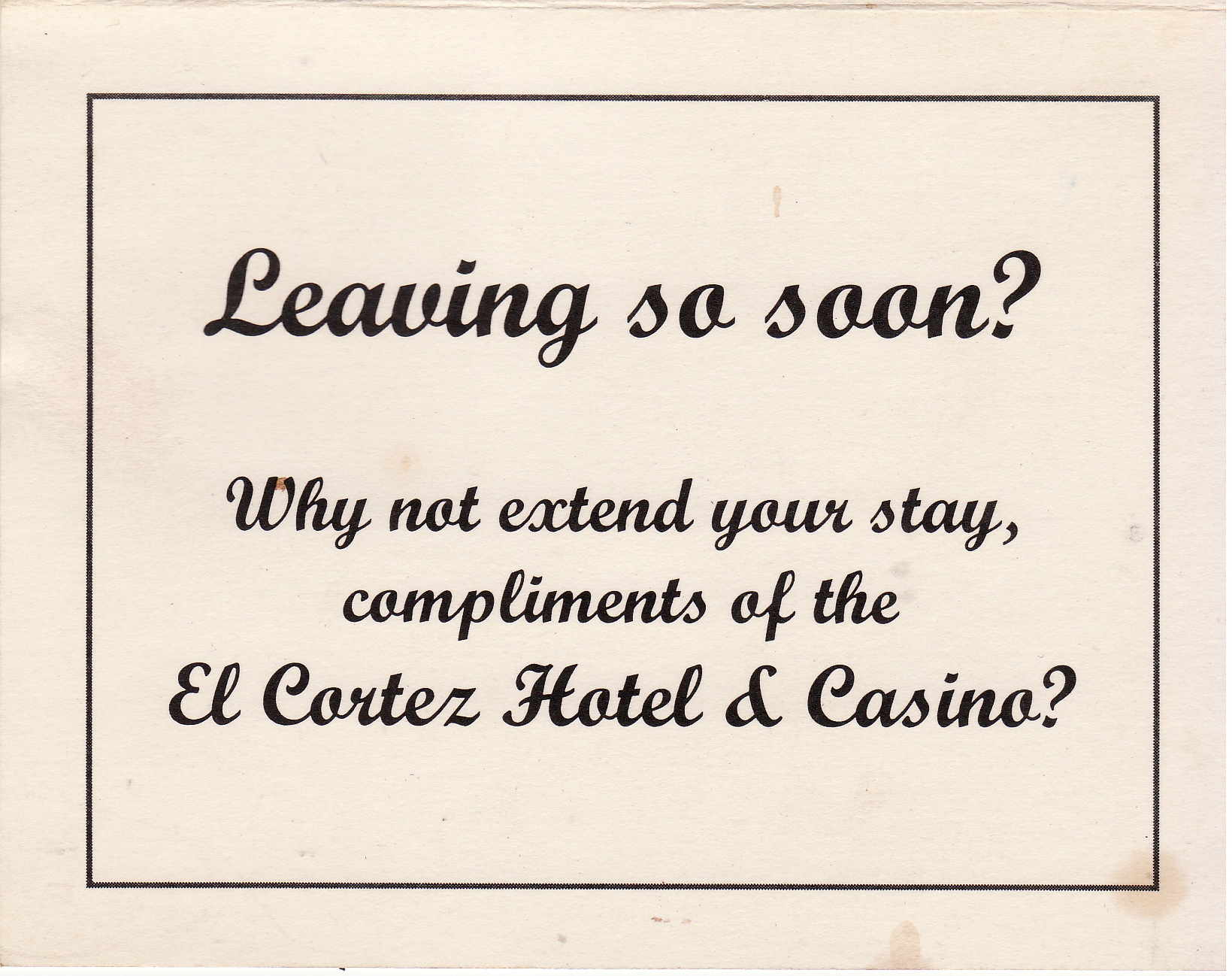

Leaving so soon?

This card, found in Lloyd’s apartment — along with a staggeringly diverse collection of books, manuscripts, DVDs, BluRays, laserdiscs, vinyl, paper ephemera, action figures, his Western saddle and the bust of Elvis, among much, much more — is a nice reminder that when Lloyd first moved to Las Vegas, he stayed for a considerable time in the El Cortez. He loved that it was the oldest casino still operating in Las Vegas, in all its dingy glamour, its façade unchanged, the first casino Bugsy Siegel owned.

The card of course also reminds us that Lloyd did leave too soon. Perhaps we can extend his stay here on mardecortesbaja. Please feel free to suggest in the comments how best we could try to do that.

For starters, here’s a link to the precursor set of his on-line writings, Nowhere Confidential, dating from his 2004 arrival in Fabulous Nowhere into 2006, as he was about to start mardecortesbaja, and containing links to even earlier collections of posts, among them the Report from Gotham and the Report from the Beach, when he was living in Ventura, California.

LLOYD WILLIAM FONVIELLE, JR.

March 22nd, 1950 — February 19th, 2015

Lloyd Fonvielle, a writer whose prolific career encompassed erudite essays on photography, screenplays for Hollywood and freewheeling short stories about the American West, died on Feb. 19, 2015 at his apartment in Las Vegas, Nevada. He was 64 years old. The cause of death was hypertension and COPD, according to the Las Vegas coroner’s office.

Mr. Fonvielle was a working writer in Hollywood for more than twenty years. His produced screenplays included The Lords of Discipline (1983), The Bride (1985) and Gotham (1988), starring Tommy Lee Jones and Virginia Madsen, which Mr. Fonvielle also directed. In 1996 he wrote Little Surprises, a 36-minute comedy directed by Jeff Goldblum that earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Live Action Short. He was accorded story credit on the 1999 blockbuster The Mummy, and on Cherry 2000 (1985), which he also executive produced.

Among his writings on photography were the introduction to a book on the iconic photographer Walker Evans, published by Aperture, and the preface to Election Eve, a book of photographs by William Eggleston, published by Cotty Chubb. Essays on ballet and diverse other subjects also appeared in The New York Times, Salon and Slate.

Mr. Fonvielle was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, on March 22, 1950. His father was an Episcopal minister and his mother a grammar school teacher. He grew up in North Carolina and Washington, D.C., where an obsession with movies began at an early age. He attended prep school at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, and spent a year at Stanford University before dropping out to pursue his writing. In 1983 he married Toni Bentley, a dancer with the New York City Ballet and a writer. They separated in 1992.

For thirty years Mr. Fonvielle lived in New York City and Southern California before relocating to Las Vegas in 2004. There he reinvented himself as a blogger and author of Western fiction. His blog, Mardecortesbaja.com: A Journal of Visual Culture was a platform for his literate, highly opinionated, often irreverent views on popular culture, art, history and religion (with the occasional vintage pin-up thrown in), attracting hundreds of thousands of page views.

Mr. Fonvielle was an early adaptor of Amazon as a vehicle for publishing his noir novellas and Western short stories, which found an enthusiastic audience among discerning readers. He passed away at his writing desk – in other words, he died with his boots on.

Mr. Fonvielle is survived by his mother, Laura Roe Fonvielle, sisters Libba Marrian, Lee Rossi, Anna Gratale and Roe Goch, as well as numerous nephews and nieces. At this time, funeral arrangements have not been made.

Text by Hugh McCarten; photograph by Langdon Clay (ca.1978)

♠ ♣ ♥ ♦

At the moment, plans for this site are undetermined. The family intends to keep it open for the foreseeable future. Perhaps it can be used to publish some of Lloyd’s writing, letters, ephemera, and images.

[The post was edited on March 8th, 2015, to include the fact that Mr. Fonvielle married.]

A TITIAN FOR TODAY

A VALENTINE’S DAY GIFT TO YOU

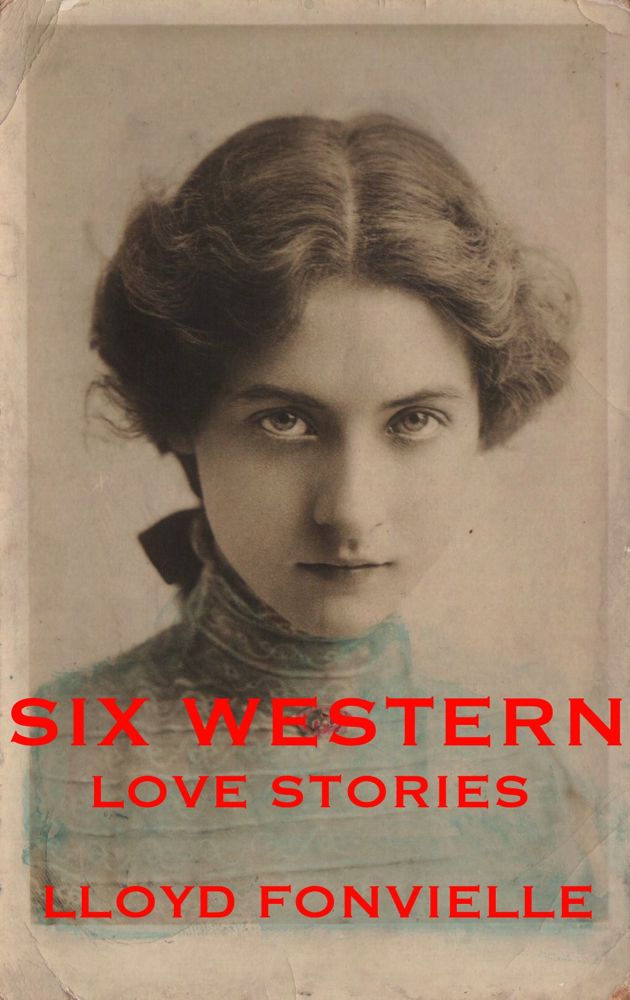

This book is a Valentine to the American West — a little raunchy at times, a little violent at times, but so was the American West. There’s a kind of romance at the heart of every story, though, and you can experience the whole collection as a free download from Amazon for five days starting on Valentine’s Day.

Go here tomorrow and enjoy — for free:

THAT LUCKY OLD SUN

This is a kind of synthetic folk song, like “Old Man River” — a Tin Pan Alley evocation of the existential laments found in the black musical repertoire. “Synthetic” doesn’t mean phoney — it’s more like a paean to the sublime vernacular expressiveness of the spiritual and blues traditions. You might see it as a form of minstrelsy, in which a white artist wants to say something he or she can’t say in his or her own persona but can say in blackface.

Blackface wasn’t always patronizing — sometimes it facilitated a profound and humble and loving tribute to black style, black culture. The performance history of “That Lucky Old Sun” has transcended racial boundaries. The best versions of the song have been done by black artists — Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin — just as the best versions of “Old Man River” have been done by black artists.

Sinatra’s version above is way too white — it’s like an academic commentary on an African-American song. It doesn’t enter into the black idiom the way the song’s (white) composers entered into it. Bob Dylan, a white singer who has always had a special feel for the blues idiom, has performed the song a number of times over the years.

Above Dylan sings it back in 1985, when his voice was stronger and sweeter than it is today. It’s a lovely performance but it’s got nothing on the version that closes Dylan’s new album Shadows In the Night, which is moving beyond my ability to convey, except to say that I’ve listened to it twice and it’s made me cry twice.

Black blues singers regularly performed, but rarely recorded, Tin Pan Alley songs written by white composers. (Ray Charles, whose musical taste acknowledged no boundaries, offered his version of “That Lucky Old Sun” on an album that also included “Old Man River” and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”.) White artists have often been moved to try and sing the blues — with mixed results. This is all part of the complex conversation of American musical culture.

Dylan’s version of “That Lucky Old Sun” on his new album is one of the most eloquent contributions to that conversation in the whole history of American recorded music.

Thanks to reader Ken for bringing the 1985 performance to my attention!

AN LP COVER FOR TODAY

WHAT’LL I DO?

This is one of Irving Berlin’s most brilliant songs — a lovely melody with deceptively simple lyrics. The iterated question “what’ll I do?” has a casual feel, but becomes an existential cry of hopelessness, particularly with this line — “When I’m alone with only dreams of you . . . that won’t come true . . . what’ll I do?” That first ellipsis requires a subtle but perceptible pause to achieve the full impact of the line, suggesting a sudden realization or final acceptance of the unthinkable — this love affair is over forever.

When Sinatra first recorded the song in 1947 he didn’t make use of that pause — he was more concerned with delivering a mellifluous vocal performance than with plumbing the song’s emotional depths. By the time of the 1962 recording above he’d grown as a dramatic artist and sang the line about as well as it can be sung. Gordon Jenkins’s arrangement for the 1962 recording isn’t ideal, though — it’s a little overblown, going for emotional effects he should have left to Sinatra.

Dylan delivers a superb rendition of the song on Shadows In the Night. He knows as well as the 1962 Sinatra how dark the song is and his aged voice gives it an edge that makes it even darker. He doesn’t go for the pathos in the lyric in any obvious way — his phrasing, like Sinatra’s in 1962, is casual and straightforward, allowing Berlin’s words to take the song where it’s going . . . straight into a terrifying emotional abyss.

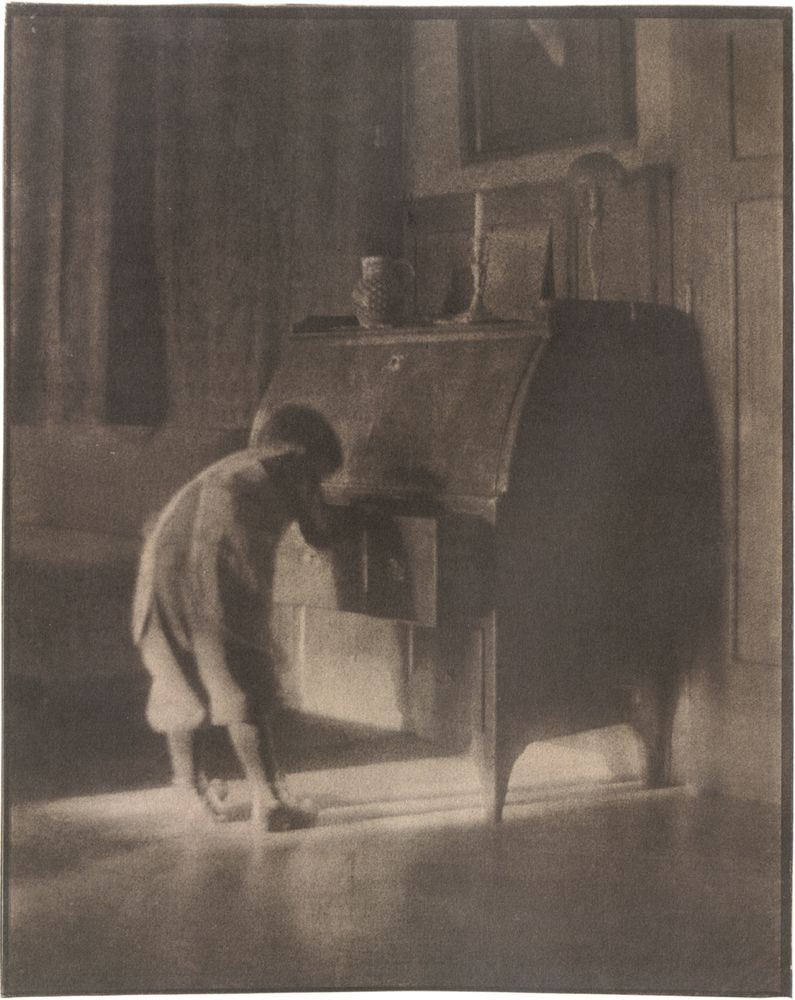

A HEINRICH KÜHN FOR TODAY

WHERE ARE YOU?

A brilliant performance of a magical song — one of the highlights of Sinatra’s years at Capitol, which were pretty much a non-stop parade of highlights.

Dylan sings it on Shadows In the Night with the same emotional commitment Sinatra brought to the song, though Dylan’s vocal doesn’t have the subtle perfection of Sinatra’s, with its mix of masterful musical calculation and dramatic intimacy. This is the one song on Dylan’s album to which Dylan doesn’t bring anything new. His is just an excellent rendition of an excellent song.