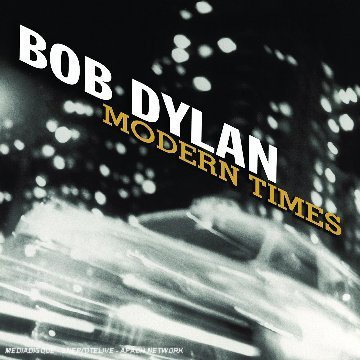

Bob Dylan’s new album “Modern Times” sounds as though it was made by people playing musical instruments, by a man singing with his voice, all in

some sort of space that might actually be encountered in the real

world. This is very unusual in modern popular music, and you might call

it revolutionary, even though it harks back to the sound of recorded

blues, rhythm & blues and rock & roll well into the 70s. (A

sign that the album’s title might be ironic is that its cover sports a

black-and-white photograph from the Forties.)

Beginning in the 70s, popular music began to take on what Theodor Adorno would have called a “phantasmagorical” quality — a process which he

explained in terms of the modern commodity culture, which tends to

produce objects which do not easily reveal how exactly they were made.

The commodity seller benefits from this because it obscures the fact

that he himself has not made the object he’s selling but appropriated

the labor of others to make it (perhaps unfairly.)

Adorno saw the same process at work in the music of Wagner, where a great wash of sound enchants us away from an appreciation of the fact that the

music is produced by individual musicians playing individual

instruments. (Stravinsky, who hated Wagner’s music, once wrote

passionately against the practice of listening to live music with one’s

eyes closed — he felt that one should never forget the physical

process of making music.)

R & b and rock sounded revolutionary in the Fifties quite apart from

their raucous beats and suggestive lyrics — they sounded revolutionary

because they sounded as though they were made by individual musicians,

not by workers in corporatized music factories. But with the rise of

disco and synthesizers and multi-track recording in the 70s, all fine

things in themselves, the recording industry had tools for resubmerging

individual performance into a corporatized “sound”. It commodified rock

and roll — made it phantasmagorical, in Adorno’s sense.

For some reason hard to fathom, “Modern Times” debuted at #1 on Billboard’s

charts and has been one of Dylan’s most successful albums ever. Perhaps

it’s attributable to the nostalgia of baby-boomers, hearing music that

takes them back to the golden age — perhaps it’s attributable to

younger listeners having their ears and minds opened up by something

that sounds different, new.

Most likely it’s a combination of the two — part of the old rascal Dylan’s strange alchemy whereby old forms and old language are somehow deconstructed and recombined to reflect the peculiar aura of the present moment.