Certain Hollywood comedies from the 60s seem to have been designed to work as sedatives. Nothing much happens in them, the plot complications are so trivial that one never really worries about their resolution, and everyone involved in the production seems to be half-awake.

There’s something pleasant about the phenomenon, in a mindless sort of way — like watching golf on television while under the influence of a mild pain-killer.

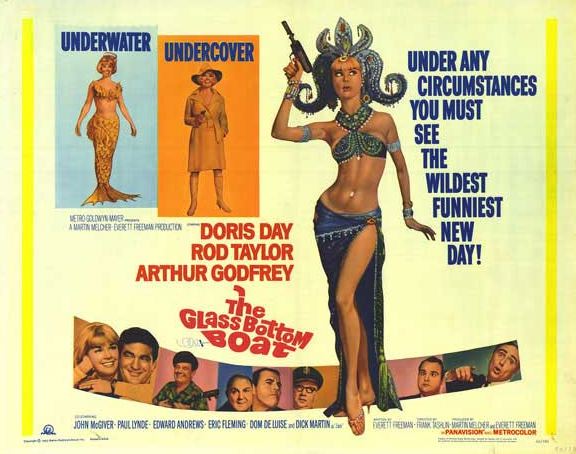

The Glass Bottom Boat is such a film. Doris Day and Rod Taylor have some minor misunderstandings on the road to romance. A crowd of fine character actors involve themselves in the proceedings to one degree or another, with nothing much to do except display their amusing personae in the absence of any scripted wit.

The film was directed by Frank Tashlin, who had one of the wackiest imaginations in Hollywood at the time — but he confines his energy to a few tepid bits of slapstick. Dom DeLuise puts his foot in a pie, then gets it stuck in a trashcan — then Doris gets her foot stuck in it, too, trying to help him out of the jam. When they both jerk free, Dom falls into a fish pond.

Everyone seems to be going through the motions, waiting for lunch, or recovering from it. Yet the tone of distance is so consistent, so assured, that you have to think it was deliberate — offering an anesthetic for anxiety duly indicated and professionally administered. Arthur Godfey, the personification of the entertainer as somnambulist, makes his film debut here — his practiced nullity anchors the film in its odd nether world, its sleepiness.

I don’t know why it’s all so delightful, so soothing — but I don’t really know how codeine works, either.

Perhaps these films did for audiences of the 60s what Jared Hess’s films do for us today — tell us not to worry so much, tell us that everything, as improbable as it might sound, is going to be o. k.

Vote for Pedro.