I

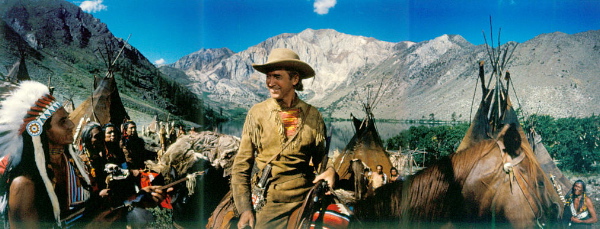

saw Lawrence Of Arabia when it came out in 1962, in the sort of grand

roadshow presentation big movies used to get back then — reserved

seating, an overture and intermission and an expensive souvenir program

on sale in the lobby (I still have mine.) My dad used to take me to

these big roadshow presentations of big films — it was one of the

great rituals of my childhood.

Lawrence blew me away back then, at the age of twelve. I saw it a few times

later and was less impressed. As an adult (and apprentice screenwriter)

I found the dialogue excessively literary and aphoristic — every line

was a bon mot, a philosophical nugget, an intellectual construction.

Real people, I thought, in real wars, don’t talk like that — even if

they’re Oxford-educated British officers or wise old Bedouin

chieftains.

Then I saw the restored version back in the Eighties, on a big screen, and

realized how wrong my second thoughts were. What I’d lost touch with

was the power of the images — the extent to which the images are the

story of this film, its narrative and its subtext, its spectacle and

its subtlety. The moment of revelation came watching the shot where

Lawrence walks along the top of the captured train. His Bedouin

followers run along the ground below him. In the shot, we only see

Lawrence’s shadow on the sand — his followers chase his shadow.

This is the whole film in a single image — the essence of the filmmaker’s

view that Lawrence both invented himself in Arabia and lost himself . .

. created an image that had no substance beyond the events it inspired,

yet cast a real shadow into the future. In the last shot, as Lawrence

is driven away from the scene of his betrayed triumph, we see his face

through the windshield of an open car. A reflection on the windshield

suddenly obliterates his face, and the film is over.

This is a mode of filmmaking — in which a film’s deepest truths are conveyed

by images alone — that characterized the silent era of cinema and which is

rarely seen today except in the theoretical film experiments of

Jean-Luc Godard. I began to see the dialogue of Lawrence in a

different light — as the functional equivalent of title cards, which

offered a kind of running literary commentary on or clarification of

the images but did not drive the narrative or the drama.

In short, I realized that Lawrence is essentially a silent film — in

the same sense that Titanic is essentially a silent film, a film

whose dialogue is virtually irrelevant to the actual meaning of the

work. Relatively unsophisticated twelve year-old boys and girls, for

whom the experience of a film is primarily visual and visceral, who

feel no intellectual need to translate a film into literary terms

before being able to appreciate it, have easier access to such

sound-era “silents”. They are, in this, sometimes wiser than their

elders.

Monthly Archives: January 2007

AMY CREHORE

Check out the art of Amy Crehore, who makes delicious images that combine the sang-froid of Magritte with the innocence of antique vernacular icons and the insinuating eroticism of a high-class Parisian strip show from the Twenties:

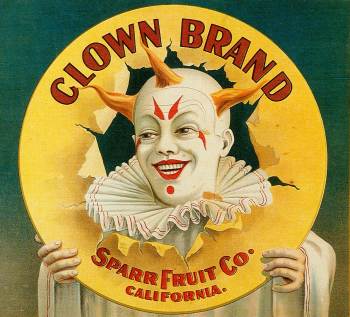

She also has a blog filled with curious images and objects that clearly nourish her strange imagination, like the wondrous fruit crate label below:

Her blog:

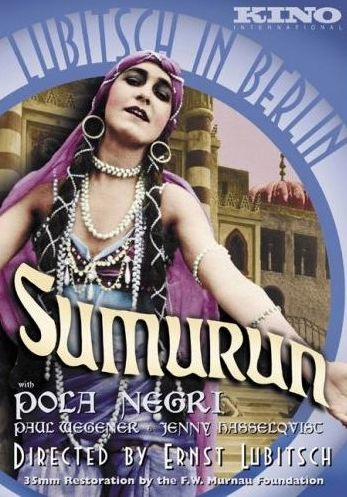

SUMURUN

In

Ernst Lubitsch's Sumurun, from 1920, Diaghilev's Ballets Russes meets

the Keystone Kops, and the result is an inspired piece of lunacy,

slight but very entertaining.

It's yet

another variation on the mood of silliness that seemed to grip Lubitsch

in the late Teens and early Twenties — a silliness that feels quite

un-Germanic. Edgar Ulmer said of Lubitsch that “he really should

have been a Frenchman,” but Lubitsch's silliness is not quite French,

either. When a Frenchman is being silly he'll always take care to

let you know how elegant his silliness is, how artful and

respectable. Lubitsch could certainly be elegant and artful, but

he was not above using vulgarity when it took his fancy. In the

early films at least he never seems to stand on his dignity, or his

genius — he strews his effects about like flower petals, or cow pies.

In this film,

we can see the two sources of Lubitsch's early style — the broad

comedy he specialized in as a cabaret performer and the more elegant

spectacle of the theater of Max Reinhardt, for whom Lubitsch did small

character roles. Sumurun is based on a Reinhardt pantomime, and

it's full of stylish (though silly) choreography and charming scenic

effects. Lubitsch himself plays the role of a grotesque clown in

love with a dancing girl in his troupe, and offers a few examples of

his eccentric dancing along with a bigger dose of his highly stylized

acting. His performance has been criticized for its exaggeration,

but I see a lot of art in it, and the theatricality doesn't seem out of

place amidst all the artificiality of the film as a whole.

Lubitsch doesn't seem to be taking himself too seriously, even when his

character is.

The narrative

feels disjointed and is hard to follow at times, probably because the

version that survives is missing about four reels cut by its American

distributor. It hardly matters, though, because the story is not

all that important — it's just an excuse for some pleasant diversion

in an Arabian Nights vein.

Pola Negri

plays the dancing girl mentioned above, and she's a real

revelation. I guess she's technically playing a vamp here, a

dancer who drives men mad, but she plays her with all the freshness and

spunk of a Kansas farm girl or Broadway hoofer. (She seduces the

Mighty Sheik with what look like cheerleading routines.) She

seems more like a flapper than an exotic femme fatale and she gives the

film a cheerful tone that matches Lubitsch's blithe approach to the

material. She must have been a breath of fresh air to film-goers

used to the ponderous dignity, and dignified poundage, of traditional

European divas.

CAULIFLOWER AND GRUYERE

How often do we take a moment from our busy lives to think about Gruyere? Not very often, I suspect. And yet it is a cheese of deep philosophical interest, simple, distinctive and useful.

There was a time when I thought of it only in connection with French onion soup, for without the Gruyere that’s melted on the piece of thick toast that floats on top of the soup, it is not French onion soup at all. It’s just brown stuff made out of onions.

I began thinking about Gruyere seriously and appropriately due to a chance remark by Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher, speaking of dining alone. She observed that it’s just as easy to eat a piece of Gruyere with a loaf of crusty sourdough bread as to down some fast-food alternative, and more nourishing to the soul, more respecting of one’s dining companion — you.

By a simple taste test, I discovered that she was right. Rarely has a philosophical observation been so easy to prove.

I began reading other gastronomical observations by Fisher with a keener interest. I could not test all of them practically, since my kitchen facilities at the time were limited — no oven, just two electric burners and a toaster oven.

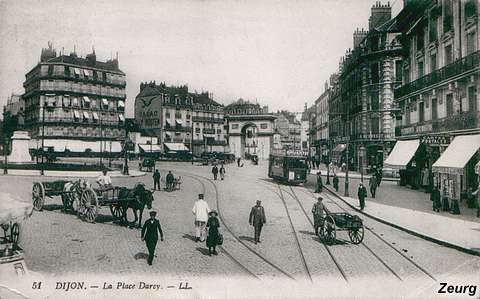

But then I read about the first kitchen Fisher presided over, in Dijon in 1931. It had no running water (which had to be carried in from the landing) or ice box . . . and its stove consisted of two gas burners with a tiny cover that could be fitted over them by way of an oven. My excuse vanished, and I decided to make one of her specialities from that time, for which she gives no rule, just a vague description. But it was enough.

You take a head of cauliflower and split the fleurs apart, in clusters that

are not too small or too large — enough of them to cover the bottom of

a baking pan. Boil them for about three minutes, no longer, drain them

and lay them in the pan. Pour heavy cream over each of the fleurs, enough so

that the cream covers the bottom of the pan to a depth at least halfway

up the sides of the fleurs, and then perhaps a little more if you feel

reckless.

Put a lot of fresh grated Gruyere on top of the fleurs and the cream, enough

to make a somewhat less than solid layer of cheese over the whole

thing, part of it floating, part of it on the fleurs. Then grind fresh

pepper over it all.

Bake it in an oven at maybe 350° (Fisher doesn’t say, because her little oven probably didn’t have a thermostat.) Certainly no lower.

When the top of the thing is toasty brown, take it out. (Fisher wasn’t quite

sure why her little oven browned the top of the dish. It must have been

because enough of the Gruyere stayed on top of the bubbling sauce to

get toasted, and it worked the same way in my toaster oven. In a

real oven you need to place the pan on a high rack to get the same effect.)

Eat it immediately, with some full-bodied red wine of whatever

simplicity. A Cahors would be cool, if you could find it.

Have some good bread to dunk in the strange, rich sauce in which the Gruyere has and has not quite merged with the cream.

This is the meal — barring some salad or desert afterwards, if you care about those things.

When you eat this meal, the word elegant will not spring to mind. The words perfection, miraculous and inspiring will.

First of all you will have a connection with certain evenings in Fisher’s long-vanished life in Dijon — a connection which can only be described as complex. It makes you feel sad and hopeful, all at once.

Second, you will never think about cauliflower again in quite the same way — and I say this as someone who almost never thinks about cauliflower at all.

Third, you will discover a new aspect to the complicated personality of

Gruyere. As with French onion soup, its flavor will make you feel like

a virtuous old peasant. In this dish, it will make you feel like a

virtuous old peasant whose kindness has touched the lives of heroes and

saints. (This is the inspiring part.)

I am perhaps diluting the absolute virtue of the experience by sharing it here, but really, how can I keep quiet about a thing like this? Any more than Fisher could?

THE BELLBOY

It’s impossible to categorize Jerry Lewis’s movies, and that’s why it’s

always been hard for critics to appreciate him — or even to see his

work for what it is. It has roots in vaudeville and silent film and

circus clowning, and owes much to the antic, animation-inspired cinema of Frank

Tashlin, who directed some of Lewis’s early films, but the influences

are all mixed up in an eccentric blend that has no obvious continuity with any cinematic tradition. He was a genuine radical whose popularity kept his films free from the

controls of corporate Hollywood and gave him the opportunity to follow

his instincts wherever they happened to lead him. There’s a

resulting lack of discipline in his movies that makes them disconcerting on an

intellectual, aesthetic level — unless, like the French, you find

their conceptual incoherence intellectually and aesthetically

satisfying.

The Bellboy, the first film he directed, remains

unsettling a quarter century after it was made. It embodies a unique

sensibility unmodulated by the cinematic conventions of its day, or

ours. It’s best viewed and enjoyed as a critique of those conventions,

spiced with moments of hilarious visual and verbal comedy — and as the

debut of the most original provocateur ever to function within the nominal

boundaries of the Hollywood mainstream.

WALT AND SKEEZIX

It’s an exciting time for fans of the classic American comic strip. A few small, quality-minded publishing houses are issuing handsome new reprints of some of the glories of the genre — including, from Drawn and Quarterly Press, the start of a complete run of Frank King’s masterpiece Gasoline Alley. Volume two has just appeared, continuing the adventures of Walt, a genial car nut, and bachelor, who one days finds an infant on his doorstep and decides to keep and raise him.

King began his domestic epic in the 1920s (the strip premiered in 1918 but the kid didn’t appear at Walt’s door for a couple of years) and kept it going into the 1950s (when he turned it over to other artists), allowing us to watch the child, named Skeezix, grow up in real time. The strips of the early years constitute a sweet, sharply-observed paean to single parenthood and, more importantly, a deeply-felt celebration of the joys of fatherhood without equal in American art.

The strips have been unavailable for years, and never presented in complete form — check them out and cherish a rare treasure from our culture’s not-so-distant past.

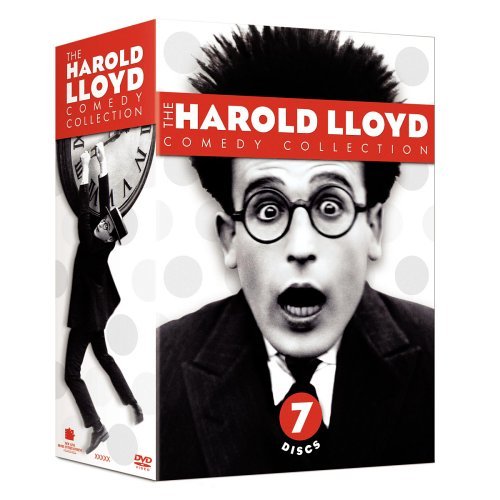

HAROLD LLOYD

The recent Harold Lloyd box set is both a miraculous treasure and a

daunting challenge.

Like most people of a certain age I got to know the work of Chaplin and

Keaton slowly, in bits and pieces, over the course of many years,

starting with the 8mm Blackhawk versions of the Chaplin Mutuals my

friends and I collected in high school, continuing through occasional

college campus screenings and the theatrical reissues of the 60s and

70s.

This gave one time to absorb the bewildering genius of these two great

artists.

Lloyd’s most important films were much harder, in many cases

impossible, to find. Before the release of the Lloyd box set I think

I’d only seen Haunted Spooks and Safety Last — enough to know that

Lloyd was a force to be reckoned with but hardly enough to appreciate

the full measure of his achievement.

Now, getting so much of Lloyd’s work all at once, in the fine transfers

on the new set, I find myself a bit overwhelmed — it’s really too much

to react to in detail — but my first impressions of it go something

like this . . .

Having watched each film in the set at least

once, it’s clear to me that Lloyd was not only a filmmaker of equal rank with

Chaplin and Keaton, but of equal rank with any filmmaker in the history

of movies. With such an artist, it makes almost no sense to

compare and contrast him point for point with his peers — one loves

him for his unique genius.

The center of that genius was Lloyd’s instinctive love for and

understanding of the film medium. He didn’t comment on it as part of

his method, the way Keaton did, but he used it with unabashed joy and

energy, and with a supreme mastery that’s still dazzling.

There is hardly any film in the new set that doesn’t have its

exhilarating moments, though this is not to say that all the films

succeed equally as unified works. What distinguishes one from the

other is a central problem Lloyd seemed to wrestle with creatively

throughout his career — the nature of the character he’s playing and

its place in the particular story he’s telling.

The “glasses character” is an everyman in the sense that he presents

himself, whether rich or poor, urban or rural, as a fellow of ordinary

capacities who is impelled at some point to do extraordinary things.

These “extraordinary things” were clearly what inspired Lloyd the

filmmaker most centrally. He usually thought up the final chase or

thrill climax for his films first, and then worked backwards to create

a narrative rationale for the action in that last reel.

Lloyd’s last reels are almost always brilliant — the narrative rationales vary greatly in kind and quality and determine the success or failure of the films as stories, as whole works.

As a general rule I would say that the films in which the glass

character is motivated primarily by a desire for success, financial or

social, are the least satisfying, even when that desire for success is

linked to the character’s desire to win the approval of a girl. These

films of course reflected the values of a different time, the Roaring

Twenties, in which unbridled material ambition was seen as a primary

American virtue, but the attitude struck even some observers of the

time as shallow and disturbing, and it hasn’t aged well.

The “romantic” premise of both Safety Last and Girl Shy is that the

glass character must achieve financial success in order to win the hand

of his beloved. This tends to undercut the “romance” angle

considerably — can’t true love rise above a concern for cold hard

cash? — and turns the “hero’s journey” into the hustler’s

progress. (In these films we see the genesis of James Agee’s brilliant

observation about Lloyd — he “wore glasses, smiled a great deal, and

looked like the sort of eager young man who might have quit divinity

school to hustle brushes.”) The last reels of both these films are so

exciting cinematically that we hardly remember what got us to them, but

the excitement is curiously unemotional, like a ride on a

roller-coaster.

Similarly, the desire of the freshman in the film of that name to be

liked by people who are frankly presented as jerks strikes an odd

note. Lloyd knew that social embarrassment, and even social

humiliation, are good material for gags, but how can one be seriously

embarrassed or humiliated by jerks unless one is a bit of a jerk

oneself? At best this tends to undercut our sympathy for the freshman

— at worst it puts us squarely in the camp of the jerks who are laughing at him,

too. The emotional set-up is off-kilter in The Freshman, as is the

emotional pay-off. We’re told that the protagonist needs to be

himself, stop trying to gain his self-esteem from the opinions of

others — but then he impersonates a football player and achieves

spectacular success on the field as thousands cheer. The episode is

wonderful, hilarious, magical even — but it doesn’t jibe emotionally

or thematically with the rest of the film.

I would argue that Lloyd’s greatest films, his masterpieces, are the

ones in which the glass character has something more interior to do

than gain wealth or status — who has some inner weakness or

selfishness to overcome before he can win the day and be worthy of his

girl.

These masterpieces would include Why Worry? and For Heaven’s Sake,

in both of which Lloyd plays a character who’s already rich but lacks

inner grit and empathy until spurred on to them by the leading lady.

They would include The Kid Brother, in which the protagonist needs to

grow up and establish his own identity in the face of obstacles both

domestic and foreign. None of these films has a last reel as awesome

as the ones mentioned above, but they’re awesome enough, and to me more

satisfying, because they reflect deeper emotional transformations in

the film’s central characters.

Because the glasses character isn’t a clown, doesn’t have a clown persona

that migrates more or less intact from film to film, Lloyd always had

to ask who his protagonist was, what he wanted, this time out. The

nature of the answers he came up with ultimately determined the overall

quality of the films as satisfying stories, as unified works of art.

Watching the business on the building in Safety Last or the

race-to-the-rescue to end all races-to-the-rescue in Girl Shy, you won’t be troubled with

such reflections — they become, for the moment, quite irrelevant. But the

next time you come back to the films — and Lloyd’s films are films

that can be watched with profit over and over again, if only for their

sublime cinematic inventiveness — you may feel differently, and long

for the more modest but more moving pleasures of Why Worry?, For

Heaven’s Sake and The Kid Brother.

THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO

The great historians of the 19th Century established

the practice of history as a science, one which had to be founded on a

massive, exhaustive research into primary sources. The industry they

displayed in this pursuit, given the difficulties of travel and

communication in their time (not to mention the lack of photocopying

machines), is almost incredible.

But their devotion to documented facts did not divert

them from their duties as storytellers and moral guides. They felt

perfectly free to interpolate fanciful speculations into their texts,

often in the guise of exposing them as such, and to share their

personal opinions about any subject that came under their eyes —

revealing nationalistic, religious and racial prejudices which later

generations of historians would shudder to confess.

And they always kept in mind their duty to literature

as well, their obligation to write in learned but entertaining prose

that could be comprehended with ease, as well as with pleasure, by any

educated person.

The general result is that these 19th-Century

historians are a hoot to read — and none is more of a hoot than

William H. Prescott, of Boston, whose History Of the Conquest Of

Mexico, from 1843, while still accepted, with reservations, as a

pioneering work of history, is almost universally admired as a work of art.

The voice of the writer is confidential but assured,

as he mocks his less rigorous peers, pronounces moral judgments on

whole civilizations, damns the scoundrels and praises the heroes who

people his epic, and parades his learning with circumspect but

unmistakable pride. He allows himself to be known.

Modern historical practice finds this sort of personal

interjection deplorable, but it might be argued that it has its own

corrective built into it. A frank confession of prejudice on the part

of a historian makes it easier to form our own judgment of his or her

conclusions than a pretense of absolute objectivity which we know is

quite beyond human achievement.

Be that as it may, William Prescott is good company,

and his great history of Cortes and the subjugation of the Aztecs fires

the imagination in such a way as to impress the results of its vast

erudition on the mind indelibly. We can correct his bias by consulting

later, more “disinterested” historians of the events in question — but

they will never make us care about them the way Prescott does.

VITORIO STORARO

When Bernardo Bertolucci and his cinematographer

Vitorio Storaro began preparing The Conformist, Storaro suggested a

visual style that would emphasize bold contrasts between light and

shadow, to reflect the conflicted nature of the film’s protagonist. He

said he thought immediately of the painting above by Caravaggio, with

its strange, not quite naturalistic lighting scheme, and tried whenever

possible to introduce similar hard edges between the dark and light

areas of his images in The Conformist.

In general, Bertolucci’s films draw on effects from painting, especially

from painting that has marked stereometric qualities. Many of the

beautiful compositions involving the urban spaces of Paris in The

Conformist seem to reference the urban landscapes of Caillebotte, an

Impressionist who incorporated the spatial dramatics of academic

painting into his work to a far greater degree than his peers in the

Impressionist movement.

Much of 1900 seems to reference the treatment of pastoral scenes in

19th-Century academic painting.

It’s hard to know how conscious the references to

19th-Century academic painting were for Bertolucci and Storaro, since

this influence had already been absorbed in the visual styles of the

great silent filmmakers like Griffith and Vidor and Murnau, who in turn

clearly influenced Bertolucci. Bertolucci

and Storaro might have tapped into the tradition at any point along the

line of its transmission. But Storaro has made clear his

indebtedness to Caravaggio, and that should lead us logically into an

investigation of other painterly influences on his work, especially his

work for Bertolucci.

I’m not sure how much such an investigation contributes to the experience

of the films, since these sorts of visual strategies and references must

work first on a subliminal level if they are to be genuinely effective,

but it’s certainly fascinating . . . and perhaps of use to other

filmmakers.

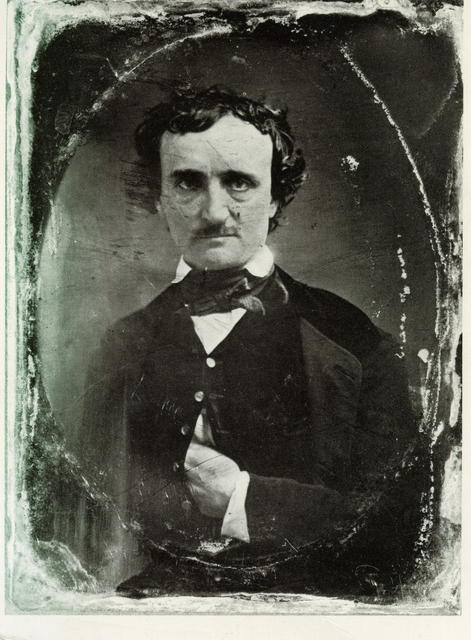

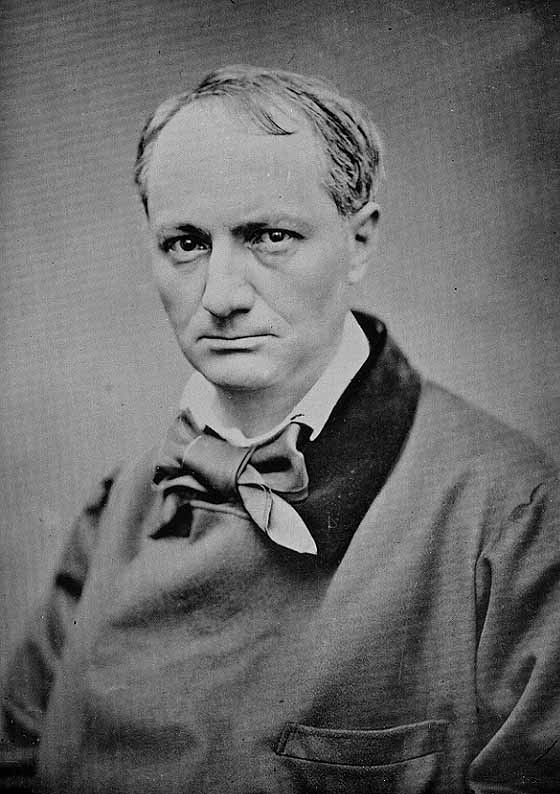

FROM POE TO BAUDELAIRE TO CHAPLIN

Here’s Walter Benjamin on Poe’s description of “the crowd” — an image

of great importance to Baudelaire:

“We may assume that the crowd as it appears in Poe, with its abrupt and

intermittent movements, is described quite realistically. In itself,

the description has a higher truth. These are less the movements of

people going about their business than the movements of the machines

they operate. With uncanny foresight, Poe seems to have modeled the

gestures and reactions of the crowd on the rhythm of these machines.

The flaneur, at any rate, has no part in such behavior. Instead, he

forms an obstacle in its path. His nonchalance would therefore be

nothing other than an unconscious protest against the tempo of the

production process.”

The Parisian flaneur was a type of 19th-Century dandy whose pleasure it

was to wander, and to be seen to wander, the boulevards with no

apparent purpose. This pose was a conscious endorsement of pure

sensibility over practical endeavor and, as Benjamin suggests, perhaps

an unconscious protest against an increasingly mechanized and

regimented industrial society.

Chaplin’s Little Fellow is a flaneur. His dandyism has become a bit

shabby but abides in his fastidiousness about his dress and its

pretension to style — well-exemplified in the Tramp’s delicacy in

removing and replacing the detached finger of his glove in one of the

opening sequences of City Lights. The pretension involved is not

about class, but about dignity. Like a true flaneur, the Tramp wanders

through the world in a state of detachment from it, observing,

sometimes mocking, sometimes hustling what he wants from it, but never

seeking its endorsement. Another remark by Benjamin on Baudelaire is

relevant here:

“Baudelaire was obliged to lay claim to the dignity of the poet in a

society that had no more dignity of any kind to confer. Hence the

bouffonnerie of his public appearances.”

Chaplin’s flaneur, like Baudelaire’s scandalous poet, had to be a comic

figure in the context of his time — his insistence on dignity in an

undignified world had to be ironical. But it is still sincere, and

heroic. The buffoonery of Baudelaire and the Tramp becomes an

accusation, and the dignity they insist on is real, if absurd in the

context of their times.

In Modern Times the flaneur is diverted from his strolling about and,

inside the factory, his movements become subsumed by the movements of

the machines, which eventually overpower and consume him. Contrast

this with Buster Keaton’s battle against a mechanized universe. Keaton

becomes a kind of uber-machine — a machine with soul and purpose and

courage, more intricate and ingenious and lyrical than the machines

he’s fighting. He bests the machines on their own terms and in that

way restores the primacy and the dignity of the human being.

But the flaneur doesn’t have this capacity, or this option. His

triumph is just to wander on, dusting the dirt off his tattered finery,

setting his hat at a rakish angle, flexing his cane, untouched by the

more profound shabbiness of the world around him — a hero not of deeds

but of example.

THE WIDESCREEN MUSEUM

This is one of the great film websites — informative and entertaining, devoted to all varieties of widescreen movie formats:

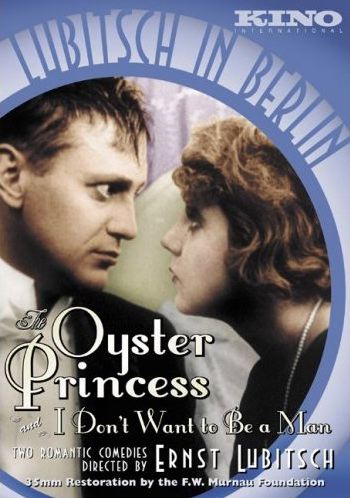

THE OYSTER PRINCESS

The first thing to be said about The Oyster Princess, from 1919, one

of the films recently released in Kino's “Lubitsch In Berlin” series, is

that there's little evidence in it of “the Lubitsch touch” — that

gossamer comedy of suggestion and indirection that came to characterize

the director's mature style.

The Oyster Princess is very broad farce, verging on slapstick at

times. That said, though, the film, for all its aggressive silliness,

has remarkable stylistic assurance and consistency — it's witty,

charming and often very funny. What it resembles most closely are the

operettas of Offenbach, or rather of his librettists Henri Meilhac and

Ludovic Halevy, which manage to combine delirious frivolity with an edgy

satire of aristocratic pretensions. The style is frothy and subversive

at the same time.

The Oyster Princess has a preposterous plot, involving a marriage

under false pretenses, and equally preposterous depictions of

aristocratic dementia that often veer into the realms of the surreal.

(In some ways they are lighter-hearted versions of Von Stroheim's dark

and grotesque portrayals of these same aristocratic circles.) But

there's more to it than that, just as there's more to Offenbach than his

farcical plots — there's Lubitsch's extraordinary cinematic

imagination, which at times causes the film to soar into the same

ethereal realms that Offenbach's music inhabits.

The wedding scene, for example, involves the sublime choreography of an

army of servants in action, and an even more delirious set-piece in

which the guests, and even the servants, break out in an hysterical

episode of fox-trotting — travesties of actual behavior organized with

exhilarating plastic grace. The film transcends itself in these

moments, just as Offenbach's melodies transcend their dramatic vehicles.

So if “the Lubitsch touch” isn't on display here, except in a few stray

scenes, the Lubitsch genius explodes often enough to make us realize we

are in the company of a master of the medium, even if he's a master

still in search of a distinctive personal style.

BEYOND COOL

Some toys just are. Above is the Sideshow 12-inch action figure of Lon Chaney in his Masque Of the Red Death costume from The Phantom Of the Opera. I still can’t quite believe that somebody made this extraordinary thing, and that I own one.

BABY FACE

In the days before its Production Code got really strict (around 1934)

Hollywood had extraordinary latitude in the subjects and attitudes it

could address. Turner Classic Movies has just released a set of three

pre-code films, under the title Forbidden Hollywood, that gives some

startling examples of the freedom that was lost.

Baby Face, starring Barbara Stanwyck, presents a world-view of

jaw-dropping cynicism — a case study of bimbo feminism that would be

shocking even in a Hollywood film of today. Stanwyck plays Lily, a

girl who’s been hooking since she was 14, pimped out by her own

father. She meets an eccentric Nieztsche fan who tells her to use her

power over men ruthlessly, without sentiment or conscience, to get what

she wants. And this she does — fucking her way to the big city, and

up the ladder of success, until she’s the filthy rich mistress of a

pathetic old banker.

The passion and jealousy Lily arouses in the men she uses eventually erupt in violence, and set up a nifty blackmail opportunity for her, but also throw her into the orbit of a different sort of man than she’s used to, a man who knows all about her past but loves her anyway . . . and she finds a kind of redemption in his arms.

All the men Lily encounters, except for the last one, are slimeballs

and pushovers, and Lily never shows even a flicker of remorse about

exploiting them and destroying them. The really shocking thing is

that the film doesn’t condemn her for this, any more than her last lover

does — she’s been dealt a bad hand in life, as a woman, and she’s

played it the best way she could.

This is all dizzyingly surreal. Seeing Hollywood stars and Hollywood

production values deployed in the service of a story like this makes

one feel one has entered an alternate universe — except of course that

it’s closer to the universe we actually inhabit than to the post-code

Hollywood version of reality.

Baby Face is lurid pulp melodrama at its most entertaining, and it’s

something more, too — a vision of what movies might have been if

corporate hypocrisy and totalitarian concepts of social hygiene hadn’t

put them in an artistic straightjacket.

Rush out and get this set, and prepare to be seriously discombobulated.