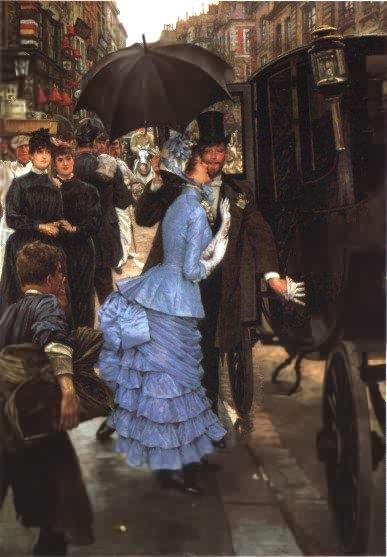

Baudelaire searched the dark back streets of 19th-Century Paris for harlots whose

painted faces, whose company and whose smiles offered him a glimpse into the abyss, exciting because it was profound. There was more than a commercial or sexual transaction going on between the poet and his flowers of evil — there was a bargaining between lost souls, a danse macabre beyond the pale of bourgeois stasis and despair.

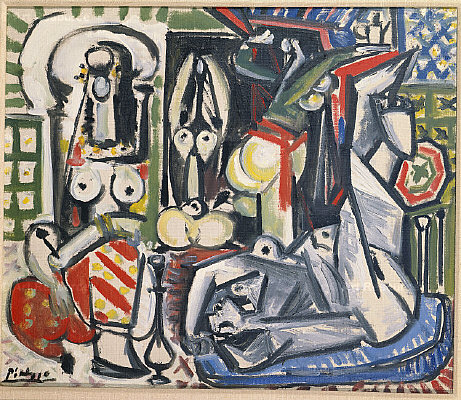

Of the painting by Delacroix above, Women Of Algiers, Baudelaire wrote, “This little poem of an interior . . . seems somehow to exhale the heady scent of a house of ill repute, which quickly enough guides our thoughts toward the fathomless limbo of sadness.” Quoting this in his Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin chose to emphasize the word fathomless.

When Baudelaire visited whores he was engaging in genuine depravity, knowing that he was violating something sacred and thus committing a profound act. He did this out of a kind of rage at what the world was becoming, a place where the sacred and the profane had no meaning, in which all values and all faiths were trivialized. He saw the birth of the world we now inhabit, the province of bourgeois superficiality, meaninglessness. He believed that this world had obliterated heaven and the possibility of heaven, but he also believed that in violating its hypocritical code of decorum, by embracing hell, he could still feel the grandeur of the profound.

Alas, even this desperate but oddly heroic depravity is denied to modern man.

What would M. Baudelaire have made of the harlots of modern-day Las Vegas, sitting at the elegant casino bars playing video poker, indistinguishable by sight from the non-working girls passing through those same bars? What would he have made of the billboards and taxicab ads, in plain view in the bright desert sun, featuring exotic “dancers” from the “gentlemen’s clubs”?

In the commercialized sexual transactions of modern-day Las Vegas, souls do

not figure. The terror of damnation is reduced to a haggling over access to body parts and the means by which a bodily emission is induced. Whatever intercourse results is undoubtedly difficult to distinguish from congress with a rubber sex doll.

Prostitution in Las Vegas has entered the realm of bourgeois commercial trafficking — honest, innocent, drained of life. Today we speak unselfconsciously of “sex workers” and the “sex industry”. In the Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin remarks that “Prostitution can lay claim to being considered ‘work’ the moment work becomes prostitution.”

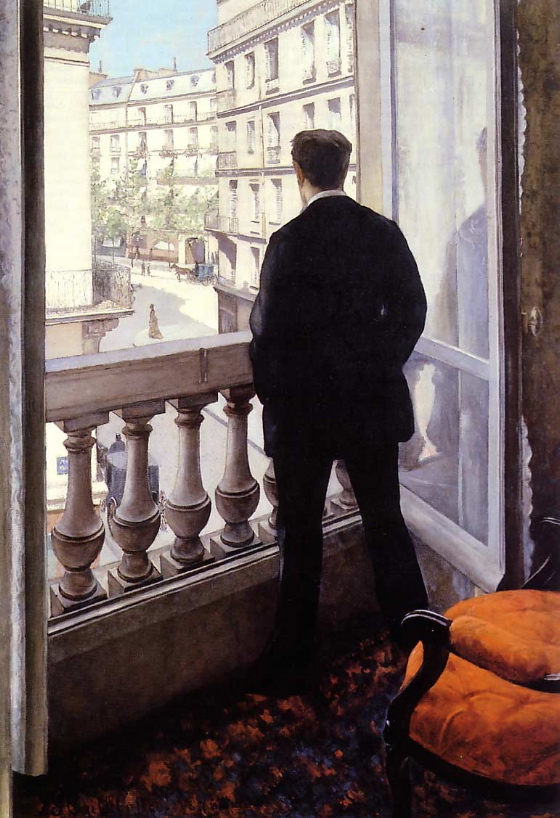

Today, it’s not just the proletariat which is alienated from its labor, but the bourgeois, too, even the haute bourgeois — the moneyed class that patronizes the “respectable” whores who work the classy casino bars.

There are undoubtedly more desperate sisters of the night working the dark

back streets of Vegas’ shabbier neighborhoods who more closely evoke the lost ladies of Baudelaire’s world, but the distinction today is more apt to seem one of style and economic status than of existential depravity. The only time you can readily distinguish a working girl from a female tourist in a casino bar is when the former opens her mouth to speak and reveals a kind of slow-witted banality of mind. (“Nobody gets into my pants for less than, like, $500,” I once heard one say — the “like” being an inelegant indication of her willingness to bargain.) She is simply less educated than her non-commercial sister, with a less developed sense of irony and play.

We’re all in hell now but we have no perspective from which to deduce that fact, and consequently there is no more glamor in damnation.

In the painting above, Picasso goofs on the Delacroix painting at the head of this post, deconstructing it. It’s not just an aesthetic exercise. It seems to me that Picasso is appropriating the bourgeois male’s hatred and fear of the female and using it to dissect the female into lifeless, if vivid and lurid, component parts. It’s possible to see cubism in general as an attempt to render three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional surface. It’s also possible to see it as an attempt to reduce three-dimensional reality to a two-dimensional object, to make it superficial, and thus conformable to the sterile bourgeois psyche.

Study the two pictures and come to your own conclusions about Picasso’s aims. Consider the use of body doubles in movie sex scenes, where disassociated, anonymous parts of the naked female body are made to stand in for the whole woman. Consider the question of whether Delacroix’s willingness to confront fathomless sadness is not more courageous than Picasso’s hysterical attempt to master it, to bring its contents up to the surface and lay them out on a butcher’s table. It may lead you to conclude that one goal of modern artists ought to be restoring the image of the whole woman to art, whatever the psychic consequences for men.