Faced with the invention of photography, academic painters of the Victorian era (like James Tissot above and Jules Lefebvre below) at first tried to compete with the new technology on its own terms — by creating super-realistic images that had the advantage

of being in color and could convey a more convincing suggestion of narrative or of the flux of ordinary life. Posed photographs tended to look posed, largely because long exposure times required subjects to stay frozen in fixed positions for many seconds at a time. The

academic painter could achieve effects with his figures that seemed in some ways, paradoxically, more naturalistic, more lifelike than anything the 19th-Century camera could capture. These effects constituted the realist painter’s only areas of advantage over the

“scientific” authority of the photographic record.

The Victorian academic painters concentrated on producing an illusion of depth in the image (again competing in this with the photograph and especially the stereoscopic photograph) and located their expressiveness in the drama of space itself, drawing the eye into the painting as a prelude to seducing the mind into the emotional content of the scene depicted, as in the painting below by John William Waterhouse:

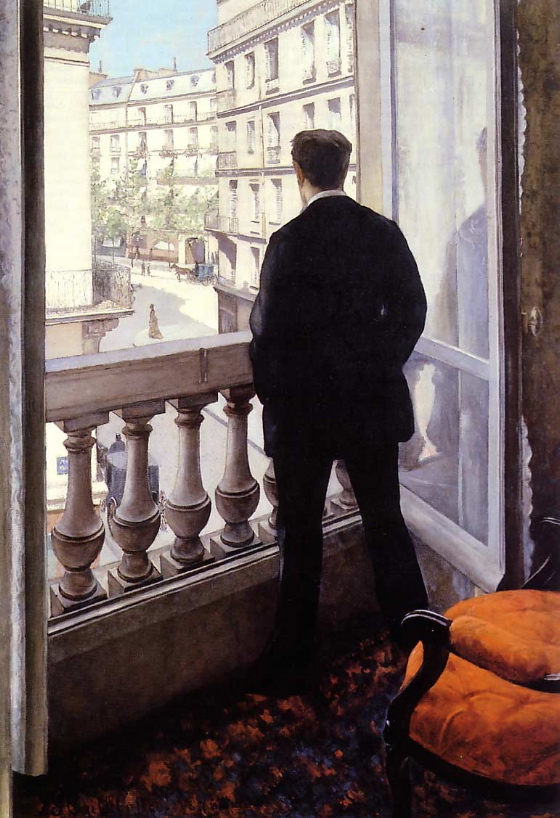

They were enormously successful in this, across a wide range of genres — from historical tableaux to contemporary social observations. The Impressionist school which challenged the academic style tended to downplay spatial drama and bring the surface texture of the painting itself, and the sheer drama of color, into prominence. The Impressionists generally abandoned historical subjects and concentrated on contemporary scenes. There were some painters who almost straddled the two schools, like John Singer Sargent and Gustave Caillebotte — but to me these two painters remained primarily in the academic camp, because a precise, stereometric modeling of forms and an insistence on the drama of space tended to loom larger in their work than either the free treatment of paint on canvas or the pure celebration of color as an end in itself.

Caillebotte hung out (and hung his work) with the Impressionists but his best paintings, like the scene below, are almost categorically academic:

Sargent, though he made his living primarily by painting portraits of the sort of people who favored academic art, was enchanted by the Impressionists’ free use of paint, but even at his most unruly in this regard he remained at heart captivated by the drama of space and solid forms, which can be seen in this exquisite interior whose subtly dramatic framing draws our eye past the surface of the canvas into the room depicted:

The invention of movies almost instantly obliterated the academic approach as a popular style, just as the radical freshness of the Impressionist school had discredited it among the intellectual

elite. Movies could render the illusion of space far more eloquently and convincingly than any painting, and were also capable of theatrical effects and a narrative complexity beyond the range of the easel painter.

A vital school of art thus virtually disappeared overnight — surviving

only in magazine and book illustration as practiced by artists like N.

C. Wyeth and Norman Rockwell. But the influence of the school

endured, because filmmakers drew on it for basic strategies of

composition in cinematography, basic notions of how to charge space

with emotion. Indeed, Victorian academic painting had far more to

do with the development of movies as an art form than Victorian

stagecraft, which is usually the arena from which movies are presumed

to have sprung.

Victorian academic painting is now thoroughly discredited

intellectually and appreciated only as kitsch, but it’s far more than

that. It was an exciting and entertaining form which deserves to

be taken seriously and studied far more carefully than it ever has been

in its relationship to the development of cinematic style. Some

of it, like the painting by Sargent below, was very fine stuff indeed.

Pingback: Listing Books: Anti-Modernism | Uncouth Reflections