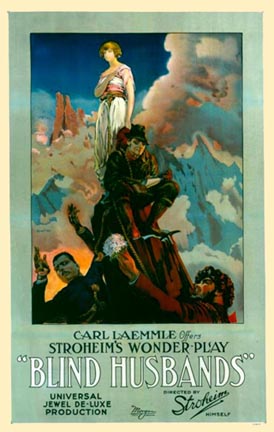

Blind

Husbands (from 1919) remains the most astonishing directorial debut in

the history of American movies. The film has been compared to Citizen

Kane in that regard, but it has also been pointed out that Welles's

startling debut was preceded by a significant body of work in theater

and radio which brought him serious critical acclaim as well as

national prominence, and made the phenomenon of Kane less surprising.

Erich

Von Stroheim had worked as an assistant in various capacities on the

Griffith lot and for director John Emerson, and he'd made a name for

himself as a character actor doing variations on his trademark wicked

Hun impersonation. He had, in fact, more practical experience of

filmmaking than Welles did before he made Kane — but there was

nothing in his resume which could have prepared anyone for the mastery

of the medium, the creative brilliance, on display in Blind Husbands.

In this

film he managed to refine the documentary power of Griffith at his best

and combine it with an expressionistic visual poetry worthy of Murnau.

It has the feel of a work conceived for its medium alone, with no

echoes of stage practice — not surprising since Von Stroheim had no

significant stage experience himself. (He had written one unproduced

play.)

In his

biography of the director, Richard Koszarski points out that Von

Stroheim saw the importance of Griffith's obsessive concern with detail

and authenticity in costumes and settings — this was a key way of

enthralling an audience and trumping stage practice, no matter how

elaborate. Yet because Griffith usually looked to the melodramatic stage

for his narratives and only occasionally explored interiors in purely

cinematic ways, an aesthetic tension remained in his work — he always

seemed to have a foot in both worlds, that of the stage and that of the

cinema.

The tension is dissolved in Blind Husbands. There is no sense, in either interiors or exteriors, of the theatrical

“set”. The camera seems to be exploring real places — however idealized or fantastical.

Much

has been made of Von Stroheim's obsession with seemingly insignificant

details, as though it represented some kind of pathology, but this was

crucial to his method — to get actors to behave as though they were

inhabiting real places, to convince audiences that they were watching

(and vicariously inhabiting) real places.

Audiences

and critics of the time recognized the power of this approach, even if

they didn't always appreciate how it was achieved — how it moved

cinema one step further from the Victorian stage. Griffith could throw

Lillian Gish out onto a real piece of ice on a frozen river, and in the

same film shoot and stage an interior as though it were being enacted

within a proscenium arch. It was the totality and integrity of Von

Stroheim's realized vision of a cinematic universe that made Blind

Husbands an immediate sensation.

The

film cost a bit more than $100,000, and Universal spent slightly

more than that promoting it — but it brought in over $300,000

during its first year of release, at a time when the average Universal

film was bringing in just over $50,000.

Making

a film like Blind Husbands was obviously riskier than churning out

programmers, but it represented a formula for commercial success all

the same — and one curiously similar to the blockbuster event-film

formula currently followed in Hollywood. Today the money is most often spent on

special effects — but in Von Stroheim's day, his obsessive recreations

and presentations of reality must have struck audiences as very special

effects indeed, and every bit as thrilling, as cutting-edge, as

exploding Death Stars.

It should be added that Von Stroheim's method is still thrilling, some 85 years on, in a way the startling digital effects

of our time may not be in a few generations.

The

film tries for a greater psychological complexity than conventional

melodrama, and presents adulterous temptation with an erotic frankness

unusual in its time, but it is still a rather ordinary love triangle at

heart. It's the organic integration of the physical world into its

drama and the power and beauty of its images which make it magical and

memorable — a purely cinematic masterpiece.

(All

versions of the film available today derive from a cut-down re-release

from 1924. About twenty minutes were removed, and the clumsy pacing and

hurried feel of so many sequences in this version suggest that much of

the cutting simply involved the trimming of individual shots. One can

only imagine the power of the film if its images could be relished at a

more leisurely pace.)