There are some cinematographers, like Greg Toland and Vitorio Storaro, who are

auteurs in their own right — it’s worth watching anything they shoot,

whether the film is good, bad or indifferent, for the superior art and

craft they bring to each assignment.

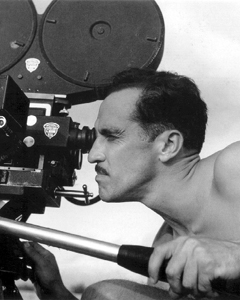

Gabriel Figueroa, the great Mexican cinematographer, is in their

class. He studied with Toland and his style is reminiscent of

Toland’s — with a concentration on stereometric lighting and deep

focus that gives his images a sculptural quality. (I’m speaking

here entirely about his black-and-white work — I’ve never seen a

Figueroa film shot in color.)

Figueroa worked for the top directors in Mexico’s fabled golden age of cinema, in the 1940s and 1950s. He shot Macario for Roberto Gavaldón, in 1959, which was the first Mexican movie ever nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar. Macario is a fascinating fable based on a novella by B. Traven (who wrote The Treasure Of the Sierra Madre.) Set in colonial Mexico, the film is sort of an existential morality play about a poor man who meets a supernatural figure in the forest

(the Devil . . . Death?) who gives him a jug of healing water. The consequences of the gift are not quite what the poor man, or we the audience, quite foresees. The film is filled with ravishing images of daily life in old Mexico, including some great footage of a Day Of the Dead celebration. A

lot of the footage is reminiscent of Tisse’s photography on Eisenstein’s aborted epic ¡Que Viva Mexico!

Figueroa shot most of the important films directed by Emilio Fernandez,

the celebrated master of the Mexican golden age — one of the most notable

being Victims Of Sin, a noirish vision in a peculiar Mexican genre, the cabaret dancer

film. These films concentrated on the heroic efforts of lower-class women to rise above the exploitation and misery of street life, mainly by working in cabarets run by sleazy underworld

thugs. There is almost nothing like these films in American cinema, though some of their themes are echoed in the films noirs starring Joan Crawford in the 40s. They have a frankness about sexuality and a brutality that still startle.

Even more startling, perhaps, is the fact that many of the greatest Latin singers

and musicians of the time make appearances in the cabarets around which

the stories of these films revolve — creating an almost surreal

contrast with the sleazy ambiance. The films are strange but

wildly entertaining.

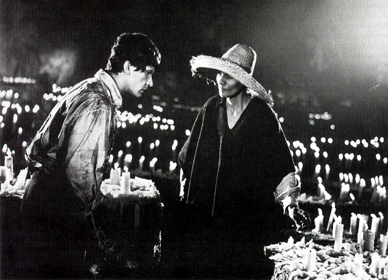

Figueroa sometimes worked for American directors making films in Mexico — John Ford on The Fugitive and John Huston on The Night Of the Iguana (below) for example.

It’s hard to find films from the Mexican golden age on DVD in this country, harder still to find ones that are subtitled — but they’re well worth tracking down. (The two mentioned above, Macario and Victims Of Sin [Victimas del Pecado] are available here in subtitled versions.) Any one of them shot by Gabriel Figueroa repays the closest attention.