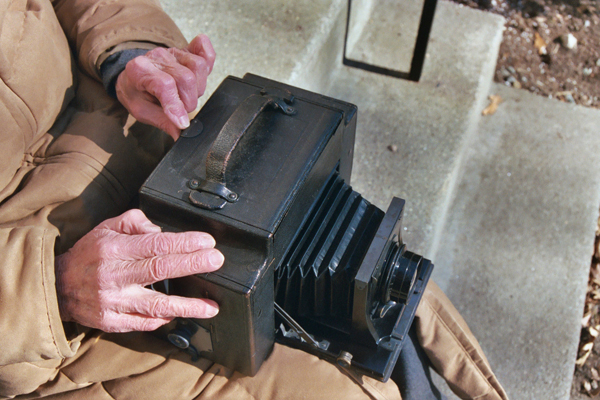

Above is a picture of Paul Zahl, the dean of a prominent

Episcopalian divinity school. He's my oldest friend. We met

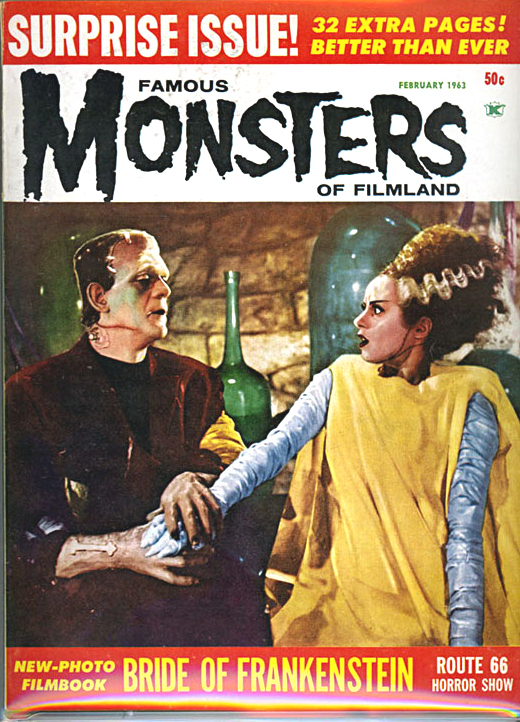

when we were 12 years-old and he introduced me to Famous Monsters Of Filmland

— and the rest is history. We were both somewhat nerdy bookworms

who shared a (for me anyway) life-changing realization — that we could

apply our intellectual powers to the stuff we really loved, like movies

and monster movies in particular . . . that we could take them

seriously. That gave me, among other things, a vocation in life

— filmmaking — as well as a source of never-ending intellectual

joy. It meant, for example, reversing the dynamic, that I could

find as much fun in Shakespeare as I did in The Bride Of Frankenstein —

that I didn't have to make the sort of value judgments between forms

that official high culture uses to diminish the prestige (and disguise

the power) of the popular arts and to turn the classics into dust.

Paul and I quickly discovered another classmate, Bill Bowman, who

shared our love of horror films, and like so many other children of Famous Monsters

in our generation we immediately started making our own versions of the

classics in 8mm, and these little epics survive as testaments to our

passion.

Paul and I

hadn't seen each other for more than two decades but when he showed up

for a visit last weekend we started jabbering away at each other with

all the excitement we shared as teenagers — talking about The Searchers, The Bride

(as we always called the mother of all Universal horror films), Blake, Dylan and theology in a continuum of appreciation that

crackled with the action of genuine intellectual adventure.

The eclectic

craziness of Las Vegas helps encourage this way of thinking about

things, in which disparate visions illuminate and deepen each

other. We sat on the terrace of Mon Ami Gabi at the edge of a

recreation of Paris, within sight of a recreation of ancient Rome and

an evocation of Lake Como and discussed the plastic eloquence of John

Ford, the precise relationship of incarnation and atonement in the

Gospels, the sly wisdom of Bob Dylan and the best images in The Creature From the Black Lagoon . . . as though all in the same breath.

It was the sort

of thing we had given each other permission to do in our youth and I

realized again what a blessing that permission truly was.

Paul brought with him a gift — the February 1963 issue of Famous Monsters, the legendary double issue on The Bride Of Frankenstein

with the stunning cover by Basil Gogos. When we saw this cover

for the first time at a newsstand, when we were 13 years-old, our pulses quickened. Looking at

it now, my blood still runs high. It's just cool. Always

was, always will be.