One of the artist’s popular desert scenes. It’s hard to imagine that David Lean, or his cinematographer Freddie Young, didn’t study these when preparing to shoot Lawrence Of Arabia, which is like a series of Gérômes come to life.

One of the artist’s popular desert scenes. It’s hard to imagine that David Lean, or his cinematographer Freddie Young, didn’t study these when preparing to shoot Lawrence Of Arabia, which is like a series of Gérômes come to life.

![]()

Alfred Hitchcock was raised a Catholic and educated by

the Jesuits. The influence of his Catholic upbringing is evident in

his films, sometimes in surprising ways.

On a purely psychological level, Hitchcock was

attracted to stories in which someone is judged unfairly,

mistaken for someone else and asked to pay for that other person’s

sins. This is a common enough response to the harsh and demanding educational

system of the Jesuits — a sense of living under perpetual (and

seemingly unjust) accusation. In many Hitchcock movies the unfairly

accused protagonist redeems himself by heroic actions — which in

theological terms might be related to the doctrine of justification by

works, the idea that a man can, with a little help from God, save

himself by his own actions.

But there’s deeper and more complex theology at work in certain of

Hitchcock’s films — most notably in I Confess and The Wrong Man.

Interestingly enough, these are two of the director’s most naturalistic

films, shot in great part on location and in black and white. It’s odd

that when he wanted to delve most deeply into religious themes he

should have chosen to present them in a quasi-documentary form.

In I Confess a priest, played by Montgomery Clift, is unjustly accused of a

murder. The real killer has confessed to him, but he can’t, as a

matter of religious conviction, tell anybody about it. In this film,

the protagonist does not redeem himself except by passive sacrifice.

His heroism is simply to accept his fate humbly, stick to his faith.

![]()

His convictions here are church-related — he must

sacrifice himself to the principle of the sanctity of the confessional,

to ecclesiastical procedure. He’s saved from paying the ultimate

penalty by the witness of another character, who sacrifices herself to

reveal his innocence. Presumably his own sacrificial posture has

inspired her to this act.

So far we are well within the Catholic tradition, which sees the church, personified in the figure of the priest, as a divine agent in the world — adherence to its doctrine and ritual leads to salvation.

But something very different is going on in The Wrong Man. Here an innocent man, played by Henry Fonda, is accused of a crime and his whole life is

shattered. He’s a religious man, and carries his rosary beads with him

through his ordeal — but it doesn’t seem to help. The wheels of

justice, the oppression of the legal system, operating quite reasonably

on the face of it, crush him like an insect.

Finally his mother asks him to pray — and he does,

not with the rosary beads, not in a church, but directly to an image of

Jesus. Instantly, the real criminal appears and is caught — the

accused man is redeemed.

This is a long way from Catholic theology in that the

church plays no mediating role. It’s just between “the wrong man” and

Jesus. He’s saved by no action of his own, not even by the humble

acceptance of his fate. He’s saved by a simple cry for help.

We’re now, oddly enough, in Protestant theological territory, closer

to the doctrine of justification by faith, in which neither the church

nor the suffering man play any role whatsoever in the man’s salvation,

which is a gift of Grace from God, pure and simple.

It’s clear that in these two films Hitchcock was not just expressing resentment over the terrors and the residual guilt inculcated by a Catholic

education. He was articulating complex themes in Christian

thought, trying to dramatize them in an entertaining way but also to

situate them in the real world, in a plausible evocation of modern-day

Quebec, where I Confess is set, and New York, where The Wrong Man

is set.

“Film is not a slice of life,” Hitchcock famously

said, “it’s a slice of cake”. But there’s very little cake on display

in either of these films — and in the mean streets of The Wrong Man,

in the suffocating rooms and cells and hallways of police stations and

prisons and courthouses, there is only wormwood and gall.

The two films stand out as great and profound works of

Christian art, explicit meditations on Christian theology in a century

(and an industry) not noted for such concerns. Like all good parables

they can be enjoyed simply as stories, but Hitchcock makes it very

clear (see the image from I Confess at the beginning of this post) that he had heaven on his mind when he made them, that he was

asking deep questions about the nature and the mechanism of salvation.

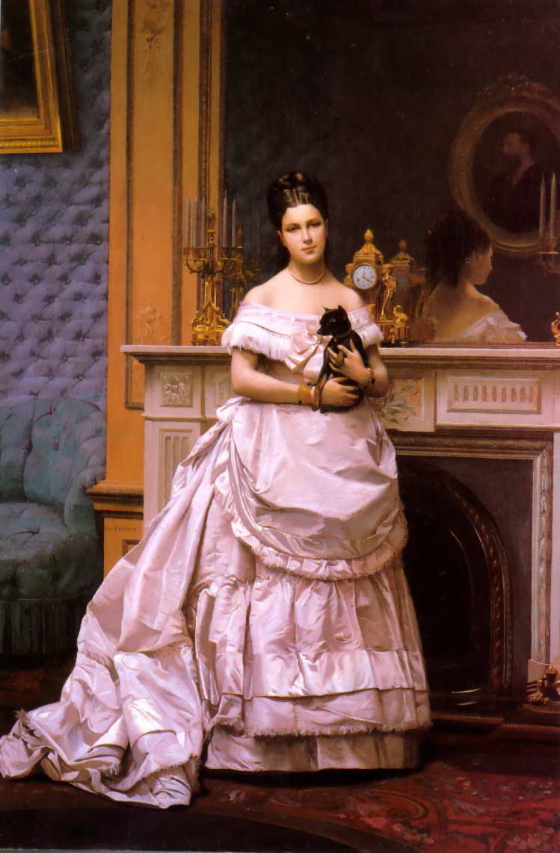

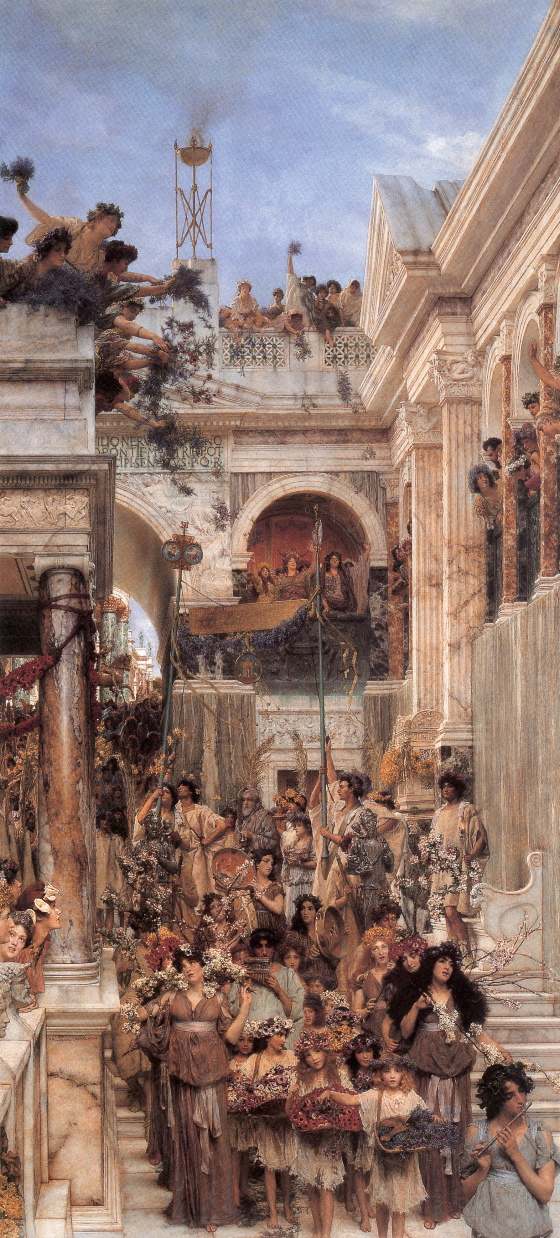

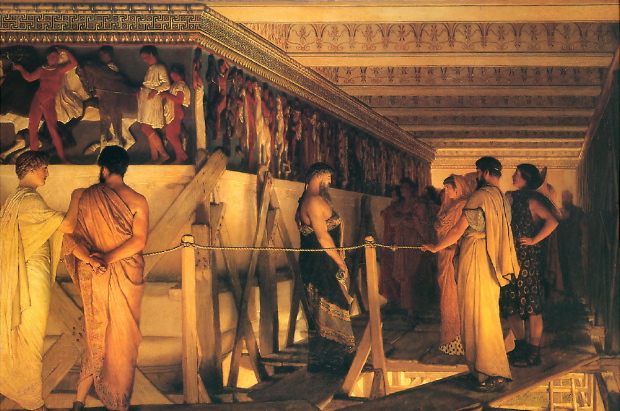

In the mythology of modern art history the realist painters of the

Victorian era fought a losing battle with the photograph and eventually

capitulated to the dominant aesthetic of 20th-Century art, with its

irresistible (and progressive) trend towards a greater and greater

abstraction, abandoning both pictorial realism and almost all narrative

ambitions.

In fact, however, realist painters of the Victoria era conducted an

exciting and productive dialogue with the photograph, incorporating its

apparent authority but also, at the same time, extending its range of

representation beyond the technical limits of the 19th-Century camera.

Academic art surrendered not to the abstractions of the 20th-Century

painter but to the great artists of the early cinema, who assumed the

narrative and representational ambitions of academic art in a medium

which had, at least as far a popular taste went, better resources for

realizing those ambitions. You could almost say that the academic art

of the 19th-Century was born again, gloriously, in a new medium, which

it deeply influenced.

Academic art taught movies how to orchestrate photo-realistic elements

into theatrical forms, using lighting, framing and the placement of

figures in space to create a hyper-realistic illusion that had the

coherence of actual visual experience even when departing from it in

fabulous ways. Because film could capture motion, and thus emphasize

the plasticity of space far more expressively than the easel-painter,

it rendered the academic easel-painter’s art passé. It was motion and

the greater illusion of spatial depth it allowed which lost academic

art its popular following.

But much more than that was lost, especially in the realm of color. Up

until very recent times, color film stocks couldn’t begin to reproduce

the range of lighting conditions which the Victorian realist painters

gloried in. By marrying, through draftsmanship, an almost photographic

realism with an über-photographic sensitivity to color and light, the

Victorian painters anticipated cinematic effects which remain difficult

to achieve even today.

The attempt to devalue the work of Victorian painters, seeing them as

obstinate blocks to the steady progress of art, was a strategic ploy on

the part of 20th-Century modernist painters and their apologists in the

academy and the marketplace. Engaged in a project which would divorce

art from popular taste and arrive at an aesthetic dead end before the

end of the 20th century, they posited a straw man in the person of the

reactionary academic practitioner which lent their own schools an

undeserved glamor and prestige — even as the academic practitioner was

informing and inspiring the great new popular art form of the movies.

But the intellectual disgrace of the Victorian painters also helped

impoverish cinema, because, after the first glorious blossoming of the

art in the silent era, filmmakers forgot academic painting. To get

back in touch with its lessons, they had to get back in touch with the

masters of the silent era, like Griffith, Vidor, Murnau and Ford, for

whom Victorian academic painting was a living form and a direct

inspiration of their techniques. The filmmakers who followed them had

to engage Victorian academic art at one remove, and thus lost touch

with the very forms which had inspired and instructed the original

pioneers of cinema.

The propaganda of the modernist painters, understandable from their

point of view, resulted in a great loss to the visual culture of the

20th-Century. It couldn’t obliterate the glories of Victorian academic

painting, which survived, transformed, in movies and in popular

illustration (through the work of artists like N. C. Wyeth and Norman

Rockwell.) But it distorted the intellectual appreciation of a visual

tradition which might have been of great use to artists, film artists

especially, if they hadn’t been shamed into despising it on principle.

I would argue that a new appreciation of Victorian realist painting has

the power to recharge the art of cinema in our time — quite apart from

the pleasures to be gained by directly encountering a vital and

ravishing visual tradition.

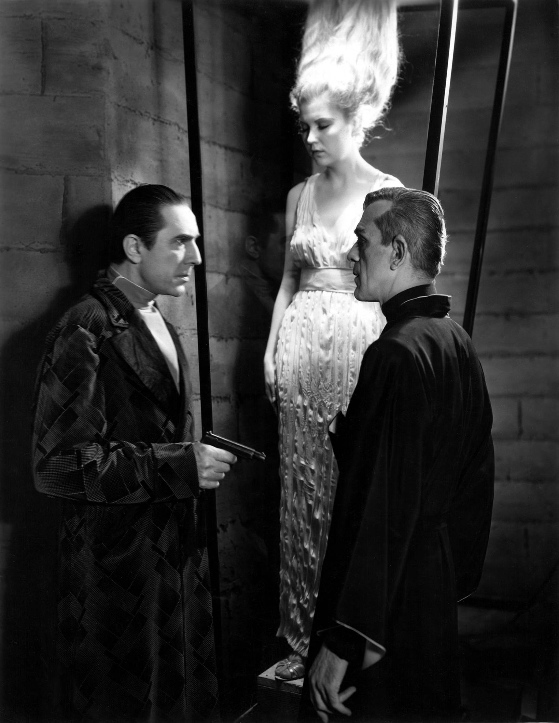

One of the most delightful sites on the Web is Dr. Macro's High-Quality Movie Scans.

Wandering through its galleries of movie stills, star portraits and

promotional graphics is a ravishing experience. Check it out.

[Above is the lovely and always vexing Jobyna Ralston, who co-starred

with Harold Lloyd in many of his best silent films. Below, a seminal

image from The Black Cat.]

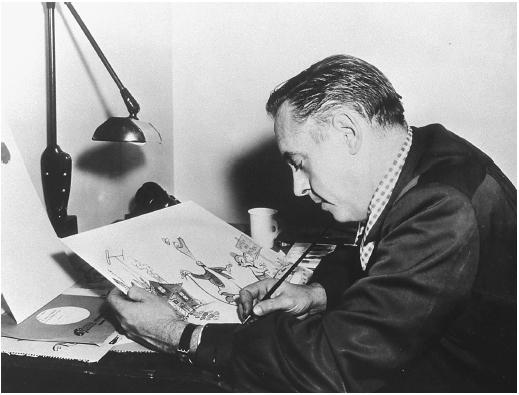

Frank Tashlin was the nut-case genius who unleashed

the nut-case genius of Jerry Lewis as a filmmaker. Before Lewis became

a director, Tashlin directed him in some important movies that helped

set the tone and strategy for Lewis' later work.

Tashlin basically showed Lewis that if in a film you

deconstructed the process of making movies and let the audience in on

the deconstruction in a lighthearted, complicitous way, you could

vastly expand the range of comic eccentricity possible in a mainstream

film. As long as the audience knew you were violating convention

deliberately and “just for laffs” it would then allow you to do and say

almost anything.

Tashlin started out in animation, so he had a good

idea of how much surrealism and aesthetic self-reflexiveness a

mainstream audience would accept. It was his genius to show how this

receptivity could be appealed to in live-action comedy.

The Girl Can't Help It, Tashlin's masterpiece,

starts out in black and white and in Academy ratio. Tom Ewell, the

male star of the film, steps forward towards the camera and announces

directly to the audience that the film they're about to see is in

Cinemascope. He waves his hands and the sides of the image expand to a

Cinemascope ratio. He also announces that the film will be in color —

more prestidigitation and the image becomes saturated with color.

“Sometimes,” he confides to the audience, “you wonder who's minding the

shop.”

Instantly Tashlin establishes a bond with the audience

based on the suggestion that the powers that be in Hollywood would give their customers

less than they wanted if they could get away with it — but Ewell, acting

on the audience's behalf, won't let the industry get away with it. The

implications of this are profound. Hollywood is the establishment,

part of the cultural compact of the nation. Once you're seduced into

suspecting Hollywood, you're ready to suspect everything.

But Tashlin doesn't leave it at that. As Ewell

chatters on, telling us that this movie is going to be about rock and

roll, Tashlin tracks in on a jukebox playing the title song, sung by

the highly suspect cultural icon Little Richard, and the song drowns

out the end of Ewell's monologue. Don't even trust the star, Tashlin

seems to be saying — don't even trust me.

I think it's probably a mistake to parse this film, and

Tashlin's work in general, looking for a programmatic critique of

movies or of American culture. Tashlin, like Nietzsche, is offering a

perspective from which a critique is possible, but he leaves the

conclusions to the viewer. Tashlin was interested in creating a

transgressive frame of mind, a frame of mind in which anything and

everything could be questioned — he wasn't interested in formulating

answers to the questions themselves. He liked, I think, the giddiness

of abandoning, of shattering received forms, the license it gave him to

free-associate — and that's what he does in this film.

The center of The Girl Can't Help It is the

iconic, cartoon-like image of Jayne Mansfield. Somehow Tashlin sensed

that the psychic chaos that could be induced by her sheer carnality was

somehow connected to the energy of rock and roll — that there was a

cultural matrix that generated both. There are times in the film when

he seems to be mocking this matrix, times when he seems to be

celebrating it. In fact he was just observing it in wonder — and

asking the audience to wonder about it, too.

There's a famous scene in which Mansfield bursts into

Ewell's apartment carrying two bottles of milk she's picked up from his

doorstep on her way in. She holds them up to her breasts like

extensions of those already preposterous attributes. On one level it's

a dirty joke. On another level it's a symbol of Mansfield's

innocence. On a deeper level it can be read as an acute analysis of

the male breast-fixation in post-WWII America — not a sexual thing at

all, at bottom, but an infantile regression, a lust for the alma

mater.

There are any number of such suggestive images in The Girl Can't Help It.

The complex ways African-Americans are presented in the film deserve an

essay of their own. One image can serve as an example — the

gorgeous African-American singer Abby Lincoln, dressed in a spectacular

sparkling evening gown, sexy and elegant, is shown on a cabaret stage lit in lurid colors . . .

singing a Gospel song. This is beyond satire, beyond surrealism

— it's an image as strange as American culture itself.

The lines of thought are never clear in Tashlin's best

work — and that's its value. In the

social currents he observed colliding and redirecting each other, echoed in the wildly clashing colors of his cinematography, Tashlin uncovered

perplexing contradictions in America culture and threw them in our

faces like so many custard pies. All we can do in response is wipe the

custard out of our eyes and wait for the next one.

His work in the Fifties was excellent spiritual

preparation for the Sixties — a cultural slapstick routine that still

challenges complacency in any form.

Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection,

a 15-disc DVD box set, might be the best bargain in the entire history

of entertainment. It includes 14 films plus a bonus disc of

extras, and can be had from Amazon for $84.99, possibly less from other sources

— about $5.70 per disc or about $6 per film. Four of these films

are indeed masterpieces of world cinema, two are minor masterpieces,

two are interesting misfires, and the rest are just superior

entertainment with bravura passages of pure, breathtaking cinema.

Each of the films has, among other extras, a short documentary about the making of it,

including some fascinating interviews with Hitchcock collaborators, and

the bonus disc has longer documentaries about the making of Psycho and The Birds. The Vertigo

disc, which offers the best DVD transfer of the film currently

available, has an excellent commentary by one of the film's producers

and by the two men who did the comprehensive modern-day restoration of

Hitchcock's masterpiece.

If you invest in this set, and an equally wondrous companion set called Alfred Hitchcock: The Signature Collection,

which has another 9 of Hitchcock's best movies for about $53, you will

never spend another restless rainy night at home in front of the

television. You will have an endless supply of enchantment. Just add popcorn.

You can check out the contents of the sets and buy them here:

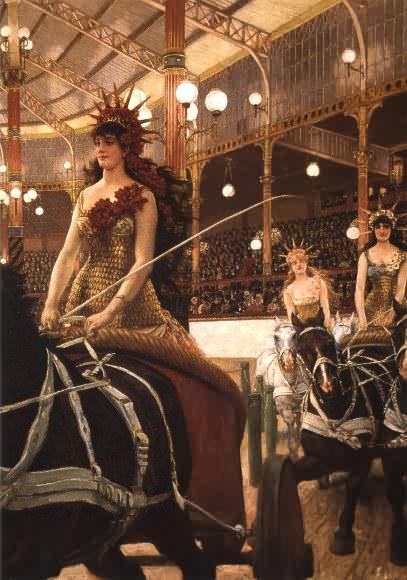

Ces Dames de Chars.

Notice how the lead horse gallops into an imaginary space in front of

the canvas, while the eye is simultaneously drawn in the opposite

direction, through a series of distinct interior spaces within the image — the bright covered arena, the darkened audience galleries — that open up

behind the lady charioteers.

To read more about Tissot go here.

Bernardo Bertolucci is one of the great masters of cinema, but he has rarely found film stories and/or scripts equal to his genius. There are passages in almost all of his films as extraordinary as any in the history of movies, but he has made more bad movies than almost any other important director. The Dreamers is one the most misguided of his misses — a stilted, inauthentic evocation of the Sixties stifled by the nostalgia of old men for their youth (the movie is based on a novel by a guy who, like Bertolucci, was a young man in the Sixties.) Indeed, nostalgia is too strong a word for it, since nostalgia implies

at least a trace of yearning, of passion — and this movie is basically a smug intellectual appreciation of the Sixties, and of youth, disguised as a drama.

There’s lots of sex and nudity — almost no real sensuality or erotic joy. And kids in the Sixties never talked the way the kids talk in this movie — not even the ones who were intellectual film buffs. The Sixties rock songs on the soundtrack and the intercut clips from films of the French New Wave, especially those by Godard, still seem fresh and alive — almost mocking the tired vision of the screenwriter and director. There are great visual passages in the film, and Bertolucci’s director’s commentary is brilliant — indeed, the film

is best seen as a pale and unconvincing illustration of that commentary.

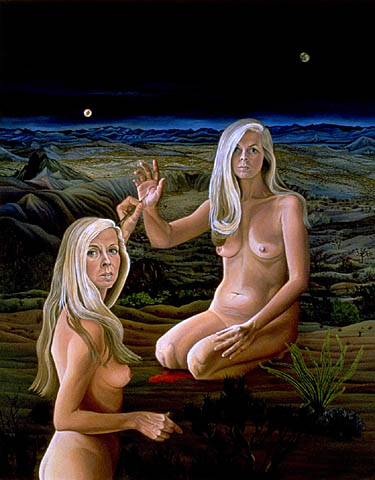

Here are some of the astonishing images of Houston-based artist Lynn Randolph. At times Randolph’s work harks back to the paintings of Frida Kahlo in its contrasts of bold, warm colors and in the placid, self-possessed sensuality of its female subjects. But it also echoes at times the hard lines and the precisely delineated dream landscapes of the painters of the Northern Renaissance. Certain paintings, like the nude on the bed below, entitled The Wetlands Of Desire, suggest the calm derangement of Magritte.

Randolph’s art exists in lively conversation with the past — not trying to be new but also transcending pastiche, as her disciplined dialogue with the vanished masters ends up revealing her eccentric sensibility more clearly than aggressive innovation might have.

The painting directly above, which must certainly be a self-portrait, offers an intimate connection with the viewer, as the artist’s eyes seem to engage ours in a moment of unguarded confrontation, just as some of Rembrandt’s self-portraits do — yet the painted image within the painted image, raising its hand as though to welcome the sensual touch of the brush, speaks of another kind of intimacy, between the artist and her work, her vision, which we cannot quite share. It has an odd auto-erotic charm.

Recently Randolph has done a series of magical dream-seacapes, like the paintings at the beginning and end of this post, which are really breathtaking.

For more info on Randolph and to see more of her paintings go here:

Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow Of A Doubt, from 1942, is a kind of proto-film-noir. It shares the dark view of human nature and the deeply skeptical vision of “respectable” society that would inform the post-WWII film noir. WWII was just getting under way for America when the film was made, but much of the rest of the world had already been at war for three years by then, and clearly the global conflagration was beginning to create a deep anxiety in the psyches of sensitive, thoughtful artists like Hitchcock and Thornton Wilder, who co-wrote the screenplay.

At the beginning of the century America had participated in a “war to end all wars” and now the continents were aflame again. There seemed to be some intrinsic, irrepressible evil in the nature of human beings, or in the organization of their societies, which led to wholesale destruction at regular intervals, despite the best efforts of mankind’s intellect and collective goodwill.

The fragility of human institutions, especially the family, was acutely sensed. Shadow Of A Doubt was pre-noir in that it didn’t concentrate on the world’s corruption or on the impotence of manhood, personified in the devouring femme fatale, but rather on the human being’s inward capacity for evil, which seemed to erupt without reason or warning. “The world needs watching,” says the young hero at the film’s end — meaning, mankind needs watching. There was still, in 1942, a faith in the idea that watching might do some good. At the core of the post-war film noir was a sense that such a faith was delusional.

The magnificent irony at the heart of Shadow Of A Doubt is that the threatened family is presented at the beginning of the film as a trap, a web of annoyance and boredom. The glamor of the unconventional, rootless, iconoclastic Uncle Charley is presented as a deliverance from the suffocating everyday reality of family and small-town life.

But as our suspicions of Uncle Charley grow, we begin to treasure the ordinary goodness of the family he seems to be rescuing from its rut. Only in the light of their fragility can we appreciate family and community for the treasures they are, the bulwarks they are against the world’s insidious darkness.

It’s easy to see how this related to the mood of the nation, and the world, when the film was made — but its resonance has if anything grown deeper as the post-war era has played out, with the family and community in deeper and deeper jeopardy, threatened now in “advanced” societies not by external violence but from within. Wilder and Hitchcock are still reminding us how truly naked and vulnerable we are in the face of the world’s horrors — still reminding us that those horrors originate in the human heart, and that our few defenses against them are both frail and inexpressibly sweet.

Shadow Of A Doubt was Hitchcock’s favorite film — he certainly never made a greater one.

City Girl, F. W. Murnau’s last Hollywood film, doesn’t have nearly the reputation

of Sunrise, his first one, but it is in some respects a greater work

and a more exciting one — if only because one can see in it Murnau’s

road to the future as a Hollywood director, if he’d lived and chosen to

remain one.

It has many themes in common with Sunrise, though here they are sometimes

inverted. A beleaguered city girl dreams of a more decent and hopeful

life in the country, meets a decent country guy who takes her off there

— and discovers the same oppression, in a different form, among the

wheatfields.

What the films have in common is a concern with good, simple people who fall

in love and whose love is tested by the meanness of the world around

them. In Sunrise the characters are iconic, almost symbolic of the

virtues they possess — they rise above stereotypes only through the

charm of the players. But the characterizations of City Girl are

naturalistic, particularized, sharply observed — greatly aided by

excellent dialogue in the intertitles.

Charles Farrell and Mary Duncan are brilliant in their roles. Farrell has the

same combination of sweetness and virility that makes George O’Brien

such an appealing hero, and Duncan’s carefully calculated balance of

hardboiled city dame and innocent dreamer is masterful. She is the

heart of the film and her experience drives it. It’s an oddly feminist

vision — the meanness of the world on exhibit here is mainly reflected

in an abuse of and disrespect for women — and Duncan’s heroic

resistance to this is thrilling, and startling. We would not see this

kind of female response to male abuse on screen in Hollywood again

until the Sixties, when it appeared in a brittle, dogmatic form far

removed from the heartfelt indignation of City Girl.

Along with the naturalism of the characterizations, more in line with

American style than the grave symbolism of Sunrise, is a less fevered

visual method — one that doesn’t announce its aesthetic ambitions

quite so loudly but that still often soars to heights of brilliance.

The long tracking shot through the wheatfield when Farrell and Duncan

first arrive at the farm, filled with hope and joy, is perhaps not as

complex technically as the moody track through the moonlit swamp in Sunrise, but it’s just as exhilarating as a piece of plastic invention and serves its dramatic moment with the same stunning efficiency and elan.

The shots of the wheat harvest with the mule-drawn machinery are equally

exhilarating, lyrical, powerful. They offer an image of timeless,

ennobling labor which contrasts profoundly with the individual

pettiness of the human characters who are operating the machines.

I think it’s fair to see City Girl as Murnau’s first experimental step

in creating a genuinely American style — one that might pass muster

among the conventional but canny minds who directed the studios, among

audiences of everyday moviegoers not especially enamored of the

European art-house mode . . . and yet one that could still incorporate his

unique plastic imagination and convey his deeply humane concerns.

It’s one of Murnau’s great films, one of the great silent films, one of the great films — its place in history, in the shadow of Sunrise, is wholly undeserved.

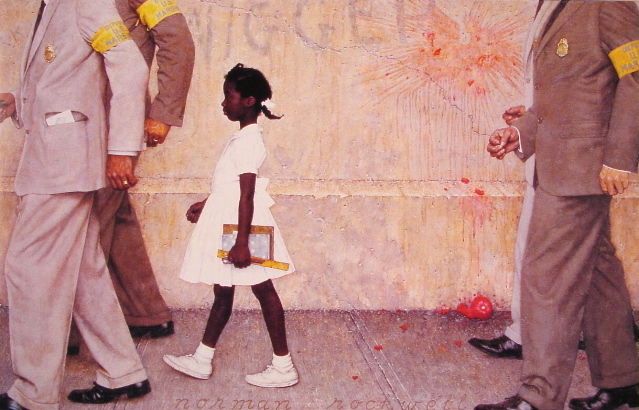

Norman Rockwell was not the least of the Victorian academic painters, even

though he lived in the 20th-Century. He perfected the

photo-authoritative aesthetic of the late Victorians and used it for

complex narrative purposes. The official Victorian academy was

swept away as a fountainhead of popular art by the invention of movies,

but Rockwell competed with movies directly and survived. Indeed,

he triumphed. His images seem like stills from imaginary

movies — movies more wonderful and moving and entertaining than even

Hollywood could turn out.

I can’t imagine that any filmmaker from Hollywood’s so-called golden age, the studio era, wasn’t influenced on some level by Rockwell’s art. Steven Spielberg, a

connoisseur and student of that golden age, has an original Rockwell

hanging behind the desk in his office.

Many modernist painters will admit to admiring Rockwell, but the

20th-Century art establishment in general marginalized and even stigmatized his work for the crime of being popular in the mainstream

culture — not just noticed and known but intensely loved — and

for embracing a tradition linked to the achievement of the discredited

Victorians.

Anyone with eyes can see what nonsense that was.

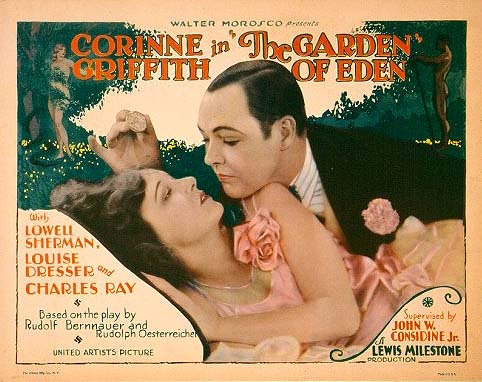

The Garden Of Eden is as charming and delightful a film as Hollywood

ever turned out in the silent era. It's also a most curious concoction

— a light Viennese-style romantic comedy directed with a kind of

gum-chewing sidewise humor that's distinctly American . . . sort of like

a Lubitsch comedy as it might have been imagined by Howard Hawks.

The film is radiant with visual invention and style — it makes its nod

to Lubitsch's visual wit but eschews his delicacy . . . the visual gags

here are more like carelessly tossed-off wisecracks.

The result is a perfect showcase for the marvelous Corinne Griffith,

appealingly casual and fresh but capable of deeper emotional

undercurrents. She was a real star. Her leading man in this

contemporary Cinderella fable is Charles Ray, who's generally charming

but threatens at every moment to become just a little too fey to hold

his own with his formidable co-star.

As Griffith's Cinderella prepares to marry her prince, she acknowledges

that almost everything she's wearing was a gift from her husband-to-be,

but adds that she provided her own underwear. When complications ensue

she removes the gifts defiantly and races through the wedding party in

her skivvies — and we're suddenly a very long way indeed from the

subtle sexuality of Lubitsch's world. Griffith's Cinderella has the

soul of a flapper, and we're relieved that her upper-class fiance has

the wisdom, finally, to appreciate her for who she is . . . and she is,

unmistakably, details of the narrative notwithstanding, an American girl, in her own underwear.

Vertigo, Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece from 1958, is about many things — that is, it can be analyzed from many different perspectives — but one of the most important things it’s about is the medium of movies itself.

Every work of art is on some level about the medium in which it’s created — its nominal subject, sometimes confused with its “content”, is often merely an excuse for a demonstration of the metaphysical resonance of a particular set of techniques. The process of art itself is a subject, a conveyor of meaning, which interacts with the nominal subject of a work in complex ways.

The technique of Jan Van Eyck’s Altarpiece Of Ghent testifies to a lifetime of study and mastery in the discipline of painting, a supreme commitment to the medium, which is inseparable from the religious devotion of the work — they become co-identical. By the same token, when Robert Rauschenberg wraps bits of an old tire around a tree stump and calls it sculpture, he is expressing a cynicism not just about art but about life, about all human endeavor.

The obvious text of Vertigo, the narrative element which can be rendered into words, clearly has parallels to filmmaking. A man dresses a woman up and coaches her in playing a part to facilitate a murder, creating an image that another man falls in love with — and when that other man loses the woman he thinks he’s fallen in love with he dresses yet another woman up and coaches her in playing the part of his lost love.

Critics have seen the images of the two men in the film as images of a film director, who on one level constructs drama for cynical, mercenary purposes, but can also, like Pygmalion, fall in love with his creation and want it, like Galatea, to come alive and embrace him.

To the degree that we as spectators enter into the activity of the director, become seduced by it — first as entertainment, then as the motivation of real desire — we share the director’s dilemma and the director’s temptation. We risk falling in

love with ghosts — the ghosts we’ve summoned, cynically or narcissistically, from our own psyches.

As I say, this analysis of Vertigo is available to us on a literary, intellectual level just from the plain narrative of the film. The art of the film, however, lies in the way Hitchcock makes us feel the spiritual jeopardy of his protagonist in personal,

often subconscious ways — to experience his protagonist’s jeopardy as our own. The genius of the film, then, is the way Hitchcock uses the medium of movies not just to express its nominal subject but to internalize it in the psyche of the spectator.

Primarily, Hitchcock does this by encouraging the pleasure we take in being spectators, voyeurs, luring us into a comfort zone about the activity, and then subtly deconstructing our comfort, our distance from the activity.

The film moves with astonishing fluidity between different kinds of images, which place us in different relationships to them. The simplest example of this is found in the early scenes in which Jimmy Stewart follows Kim Novak’s car through the streets of San Francisco. Location shots in which the moving camera, representing Stewart’s point of view, pull us imaginatively through the fascinating urban landscape of a real place, delight us and so pull us imaginatively, emotionally, into the chase narrative. But these shots are intercut with oddly quiet and dreamlike reverse shots on Stewart filmed against patently unreal backscreens. Stewart is clearly not driving a real car, he’s clearly not really in the streets he seems to be driving down — he’s watching something from a distance, as we are. Subliminally, we’re being told that we can enjoy this chase without having to imagine it as real — because it’s just a movie — but we’re also being told, and shown, that we can choose to enjoy it as real, to whatever degree we like.

This dynamic is a paradigm for the aesthetic strategy of the whole film. As the Stewart character becomes more and more obsessed by the Novak character, Hitchcock progressively eroticizes her as an image on screen, inviting us to fantasize about her also in purely sensual terms — but he keeps stepping back and forcing us to step back, to see her once again as merely an image, perhaps a

dangerous one.

Finally Hitchcock is able to bring us to the spiritual climax of the film, when Stewart is so thoroughly enchanted by the erotic illusion of Novak that he’s willing to suspend his disbelief in her reality in order to possess her, whatever the hell that might mean under the circumstances. As spectators, we are right with him. Hitchcock can tell us with every means at his command as a filmmaker that Stewart is living in a dream, that we are watching a dream, but can at the same time so eroticize Novak that we don’t care — because we want the dream to be true. We want it right up until the final shot, when, like someone having a wonderful dream he or she doesn’t want to end, we try to incorporate the sound of the alarm clock into the dream, so as not to be forced to switch our mode of consciousness.

The paradox is presented from a predominantly male point of view, but isn’t limited to one. The moment in the hotel room when Stewart waits for the embodiment of his deepest sexual fantasies to walk out of the bathroom with her hair done just so is one of the most erotic moments in all of cinema. It connects with the hope and suspense of every sexual encounter — and not just for men. Kim Novak said that the scene was incredibly powerful for her — that she was literally trembling with emotion, involuntarily, when she walked out of that bathroom, because the moment connected for her with all those amorous moments in real life when she wanted to be perfect for her lover, wanted to perfectly embody his fantasies.

The self-reflection of a film director, the spiritual jeopardy of voyeurism on the part of moviegoers, thus becomes universalized in Vertigo into a profound reflection on the hope and suspense and illusion (and charity, and fun) of sexual love. The medium incarnates the message and we receive it not as a message but as an interior insight, a wisdom born of our own experience.

This all but magical ability to incite interior experience in the spectator is of course an attribute shared by all great art, and explains why we can watch Vertigo repeatedly and still have it play out as new — much like the sex act itself. We’re not just being shown something, not just being told something, not just

doing something when we watch Vertigo. Something is happening inside

us over which we have very little conscious control — and it happens again and again each time we see the film.

If you're like me and get glassy-eyed at the thought of vegetables, if you basically hate the whole idea

of salad, yet still think it would be a good idea to eat these things

from time to time, the key to everything is sauces and dressings.

The strategy is to come up with a sauce or dressing so good that the

concept of vegetables and greens as food is eliminated — they become simply the means of conveying some sort of tasty topping into the mouth.

For salads, you can't just buy some Paul Newman's gourmet dressing and

think that will do the trick. This stuff tastes like salad

dressing — salad

dressing. It's there to “dress”, to tart up, something you don't

want to deal with in the first place. You need to be

creative. You need to make something yourself which doesn't

resemble anything you've ever encountered at the dressing station of a

salad bar.

Here's a recipe from Rick Bayless, that guy on PBS who does shows about

Mexican cooking, for creamy queso añejo dressing. Queso añejo is

a flavorful aged Mexican cheese which tastes a bit like Romano.

You can find it at just about any Mexican market (look for the kind

that's actually made in Mexico) but Romano, which you can find

anywhere, works just as well.

Start with 3/4 of a cup of olive oil in a mixing bowl or blender.

Add 1/4 of a cup of rice vinegar. Add 3 tablespoons of

mayonnaise. Add 3 generous tablespoons of grated (freshly grated!)

queso añejo or Romano. Add slightly less than a tablespoon of

salt. Add 2 to 4 cloves of roasted garlic.

Attention!

Here's the simple way to roast garlic. Put the unpeeled cloves in

a dry skillet over medium heat. Roast the cloves, turning them

often, until they're soft and splotchy brown. It takes about 15

minutes. Remove them from the skillet and when they're cool

enough to handle, remove the skins. Put the 2 to 4 cloves into

the mixing bowl or blender — if you're

going to be mixing the dressing by hand, run the garlic through a garlic press before you add

it to the bowl. (Be sure to roast a good number of

extra garlic cloves to eat while they're still warm — few things are more

delicious . . . mild, nutty and slightly sweet.)

Add some chopped-up cilantro or parsley if you feel like it.

Mechanically blend or mix (with a whisk) the contents of the

bowl. Add a little more salt to the dressing if needed then

pour it over Romaine or butter lettuce for a most delightful

dish. Save what's

left in a sealed glass jar in the refrigerator — but trust me, it

won't last long. It's just too good. You'll wonder why you

didn't buy more lettuce.