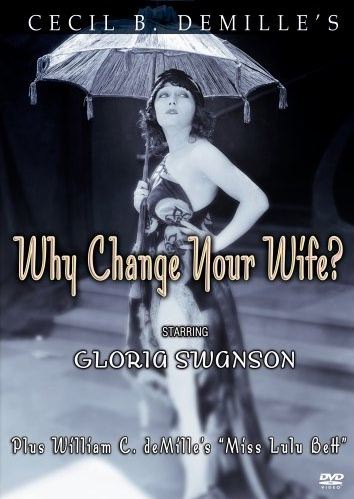

Cecil B. had a brother William who also directed films. There's a

recent DVD release which pairs two films by the brothers — Why Change

Your Wife? (from 1920) by C. B. and Miss Lulu Bett (from 1921) by

William. The first is a bit of star-powered fluff, the second is a

small masterpiece.

The story of Why Change Your Wife? is a trifle, a domestic comedy that

lurches disconcertingly into melodrama at its climax. It retails the

sort of platitudes about marriage that are familiar from second-rate

comic strips and sit-coms. A wife turns into a nag after marriage —

her judgmental and prudish ways send her husband into the arms of

another woman. Divorce ensues, the man marries the other woman and

discovers that she's just as annoying in her own way as his first wife,

who meanwhile has developed a more lighthearted attitude to life. The

ex's meet again, realize they've made a mistake — whereupon the new

wife conveniently proves her moral unworthiness in a crisis, justifying

a second divorce and the remarriage of the original couple, now grown wise.

There's nothing felt or carefully observed in the whole film, but it has

something that makes all of that irrelevant — wonderfully appealing

lead actors . . . Thomas Meighan, underplaying the long-suffering

husband with a good deal of charm, Gloria Swanson (above,) impossibly young and

girlish, impersonating the buttoned-up first wife, and Bebe Daniels (below,)

fresh and casual and funny as the second wife.

The film becomes an exercise in simply presenting the actors, the women

especially, as creatures to marvel at — their relationship to the

camera, to the medium of movies, is far more important than their

relationship to each other as characters in a story. Swanson and

Daniels incarnate movie glamor in a sweet and enchanting way and it

has an intoxicating effect. The effect wears off moments after the

movie ends but leaves you wanting more.

Lois Wilson, who plays the title character in William's film, is

something more and something less than a star. Her transformation from

drudge to romantic ingenue is far more complex and convincing than

Swanson's transformation from prude to vamp in Cecil's movie, requiring

a lot more art, and it's very moving. But it's anchored in the story —

you can't imagine her redeeming sheer fluff the way Swanson could, just

on the strength of her screen persona.

The domestic landscape of William's film also has a generic comic-book

air, but it's much more insightful about the real dynamics of a

dysfunctional family and therefore much more unsettling. There's

genuine sentiment and compassion in William's film, the sort of serious

regard for the importance and profundity of the domestic realm that you

find in Griffith's work, but it's entirely free of Griffith's

melodramatic clichés.

You might be

able to guess from watching these two films which of the DeMille

brothers would go on to the greatest commercial success in Hollywood as

it evolved in the Twenties, increasingly corporate and

star-oriented. Stars who can sell fluff are ultimately more

reliable, as a business proposition, than actors who can shine in fine

material expertly directed. Directors who understood and accepted

this basic economic truth were indispensable to the studio

system. Eighty-odd years on, when different fashions hold sway in

the marketplace, things look a bit different. Why Change Your Wife? is a delightful curiosity

— Miss Lulu Bett is a living work of art that can still touch the heart.