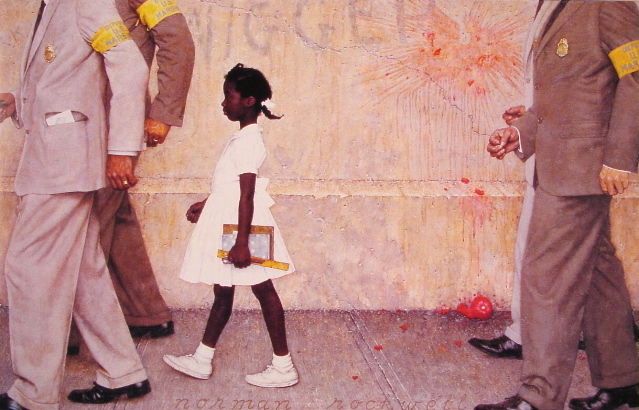

Norman Rockwell was not the least of the Victorian academic painters, even

though he lived in the 20th-Century. He perfected the

photo-authoritative aesthetic of the late Victorians and used it for

complex narrative purposes. The official Victorian academy was

swept away as a fountainhead of popular art by the invention of movies,

but Rockwell competed with movies directly and survived. Indeed,

he triumphed. His images seem like stills from imaginary

movies — movies more wonderful and moving and entertaining than even

Hollywood could turn out.

I can’t imagine that any filmmaker from Hollywood’s so-called golden age, the studio era, wasn’t influenced on some level by Rockwell’s art. Steven Spielberg, a

connoisseur and student of that golden age, has an original Rockwell

hanging behind the desk in his office.

Many modernist painters will admit to admiring Rockwell, but the

20th-Century art establishment in general marginalized and even stigmatized his work for the crime of being popular in the mainstream

culture — not just noticed and known but intensely loved — and

for embracing a tradition linked to the achievement of the discredited

Victorians.

Anyone with eyes can see what nonsense that was.