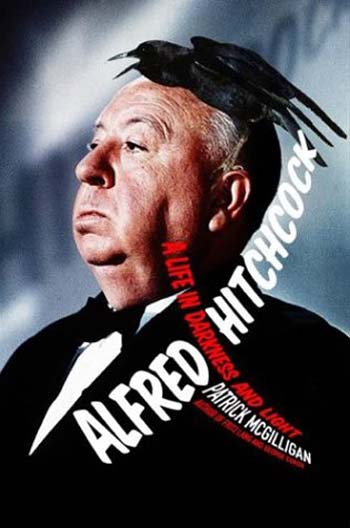

Recently I've been in the grip of Hitchcock mania. He's one of

those artists whose work is so rich that you experience it completely

differently at different stages of your life. As a teenage film

buff I thought his work was delightfully cinematic but shallow.

Truffaut's book of interviews with the director got me to take him a

bit more seriously, but not for too long. I went through an extended

period when I thought of him as primarily a master of style.

Recently, however, I've re-watched almost every movie he ever made, and

the work opened up to me in a new way. Films I'd considered minor,

like The Birds, began to reveal their subversive depths, and films I'd greatly admired, like Vertigo,

began to take their place for me among the greatest achievements of

film art — indeed, among the greatest achievements of any art.

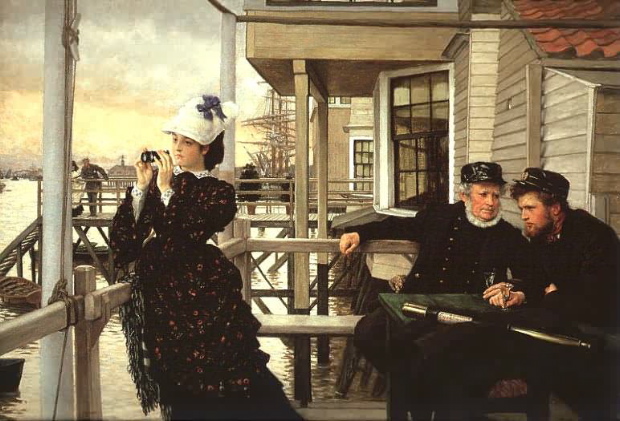

In the midst of this mania a package arrived from my friend PZ containing the copy of Look magazine pictured above, from 1962, the year PZ and I met, featuring some pre-publicity for The Birds. An object like this obliterates time — allows you to imagine The Birds

not as a famous classic from the past but as an enterprise in the

working life of a director, enmeshed in the practical contingencies of

filmmaking, which for Hitchcock always included close attention to

publicity.

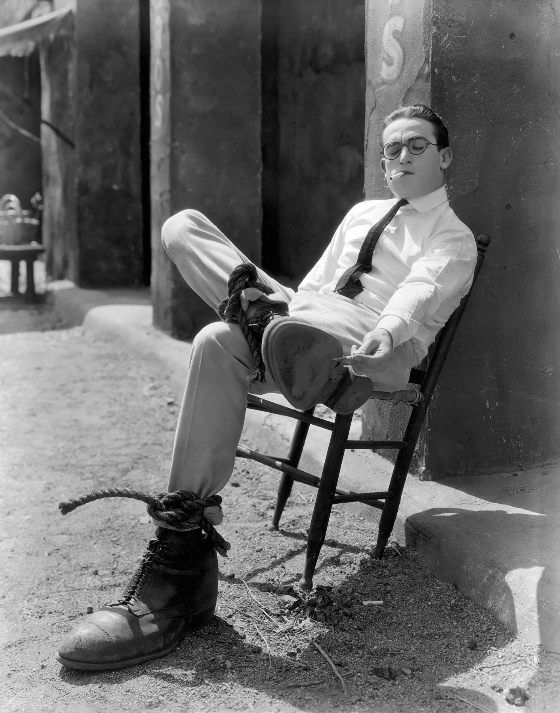

In the article inside the magazine this image appears — another time

capsule, from an age when smoking was considered elegant and sexy:

Call me degenerate but it still looks elegant and sexy to me.

The art critic Dave Hickey once observed that it was hard to imagine

any culture being both risk-averse and sexy — and it's undeniably true

that American culture has become less sexy (though arguably more

pornographic) since the baby-boomer Yuppies took control of it.

Hitchcock's movies are sexier than movies today because he recognized

the connection between moral jeopardy and the erotic. In an

amoral society, or one that confines its most passionate moral concerns to areas

of personal health, the erotic simply vanishes.

If your soul isn't on the line in a sexual encounter, in any encounter,

you might as well

be playing ping pong. Hitchcock believed in souls, and knew that

souls are always in danger, always in jeopardy, always in

suspense. Leading a healthy lifestyle, practicing safe sex, or

safe ping pong, can't deliver you from this fact — however persuasively our culture argues otherwise.