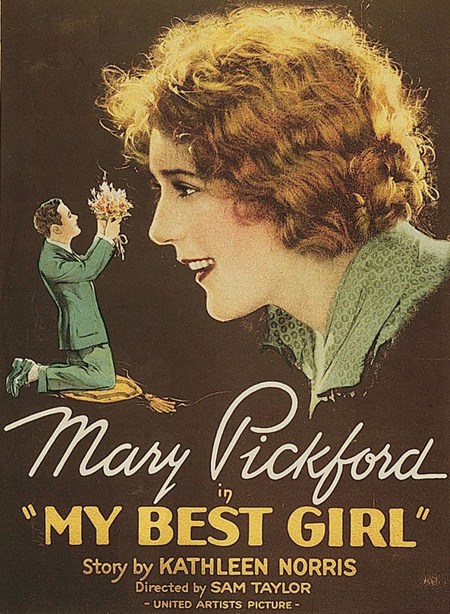

If I hadn't fallen in love with Mary Pickford watching Amarilly Of Clothesline Alley, watching My Best Girl

would have done the trick just as well.

This

is one of the best romantic comedies ever made and perhaps the

sweetest, with the possible exception of Griffith's True Heart Susie.

It's also a transitional film, I think — preserving some of the

bucolic innocence of Susie while pointing the way to the screwball

drawing-room comedies of the Thirties.

The

plot is conventional and silly, about on a level with Pretty Woman in

that regard — a young working-class woman with a job in a department

store gets involved with the wealthy son of the store's owner, who's

working there incognito to get to know the business he will inherit.

The film itself, however, is anything but a trifle. When films this

simple are this great, there's extraordinary art at work — a comment I

would also make about Murnau's Sunrise, which My Best Girl

resembles in some crucial ways. Both are simple love stories about

simple, utterly ordinary people, done without a trace of condescension

and with moments of poetry which are profound.

I'm

beginning to realize that Pickford's range as an actor was awesome.

There's a core star persona that migrates from film to film, bits of

business and attitude that reference the expectations audiences brought

to her films, but the characterizations are unusually diverse for a

star, especially a silent film star. Gish always played Gish in silent

films, though the complexity of Gish was endless — Chaplin always

played Chaplin, though the inventiveness of Chaplin was inexhaustible.

But Amarilly is not My Best Girl's Maggie — you have a sense of meeting someone

wholly different in their respective stories. (And Unity Blake, in Stella Maris, inhabits

a different universe from either of them.)

Mostly

this is the result of Pickford's uncanny ability to suggest an inner

life — to create reactions to conventional situations which are

quirky, distinctive. This has nothing to do with the roles as written,

because the roles are somewhat generic, but with Pickford's absolute

commitment to the moment, to the cinematic present. It's one of the

reasons you can't take your eyes off her.

Buddy

Rogers is a charming looking fellow, a competent actor and a very

skilled light comedian, but he doesn't convey a lot of gravity when

he's onscreen by himself. Yet when Pickford looks at him with an

expression that says, “This guy might amount to something,” you believe

it without question. So many great performances by actors on film are

created in the faces of the actors playing opposite them — Hepburn, for

example, wonderful as she is, reaches a whole new level in her work

with Spencer Tracy . . . he just very quietly gives her her scenes, and

makes us love her in a way we very rarely do when he's not around.

Pickford

does the same for Rogers here — and for the film as a whole, really.

This same film, shot for shot, with another actor as the female lead,

would be next to nothing. But My Best Girl utterly transcends its

apparent limits.

Which

is not to say that the filmmaking isn't superb — and such a treat to

experience in the DVD . . . a stunning transfer of a stunning print.

Director Sam Taylor knew exactly what he was doing. There are wondrous

tracking shots in the film, always associated with key moments in the

romantic relationship between Maggie and Joe — starting with the

thrilling shots from the moving truck where Maggie waits for Joe to

catch up with her, racing after her on foot. Plastic metaphor doesn't

get any more eloquent.

Then

there is the sudden, almost jarring pull back from the crate where

Maggie and Joe are having lunch, which becomes not just a cute reveal

but an evocation of breathlessness. It releases an emotion already

created by Pickford's performance — the physical jolt of pleasure,

surprise and fear she conveys when he accidentally puts his arm around

her, the anticipation and hopefulness in her darting eyes when he opens

her birthday present. Both moments made me cry, simply because they

were so heartfelt, yet so subtle — almost thrown away.

And

there are the fine, lyrical follow-shots as the two sweethearts walk

through the city in the rain, in the first flush of romance, dodging

cars and people, echoing a similar device in Sunrise where the bond

between two people is reinforced by their common path through an

indifferent urban landscape. In some ways, the simplicity of the shots

in My Best Girl, the fact that they don't draw metaphorical attention

to themselves, makes them more powerful.

To

illustrate the brilliance of the choices Pickford makes as an actor in My Best Girl would be to recapitulate most of her scenes in the film.

One that stood out for me was the moment when Maggie first meets Joe's

fiancée. She doesn't look at Joe, with hurt and outrage — the obvious

way to play it. She stares at the fiancée — sizing her up, calculating

the difference between them, looking into the fiancée's eyes for the

truth about what's really happening. It's heartbreaking, and a perfect

moment of perfectly observed human behavior.

It's

heartbreaking, too, to think that this was Pickford's last silent film.

You get a feeling from My Best Girl that there was some possibility

of a synthesis between the silent sensibility, Pickford's belief in

simple goodness, and a more modern style. In the final confrontation

with Joe and his father in Maggie's kitchen, Pickford seems to be

addressing this very issue — pretending to be a flapper, a hot mama,

almost pulling it off . . . but with a bitterness that seems to say,

“Is this what you really want from me?”

American movies, and American culture, lost more than we may yet realize when that synthesis didn't happen.