The picture of Reconstruction presented in the second half of The Birth Of A Nation is entirely bogus, but since it represents the views

of respected historians of the time we need to see it as expressing the

environmental racism of 1915. That it did express racism, however, is

beyond doubt. Radical Reconstruction sought to fully enfranchise

Southern blacks and bring them into full political and social equality

with whites. Its ideals were decent, and ones that almost everyone

today would heartily endorse, but it was undoubtedly unrealistic in the

context of Southern society just after the end of the Civil War. And

it wasn't only Southerners who were horrified at the notion of treating

blacks as free and equal citizens. To many, the idea was both

ludicrous and repugnant.

Unwilling to oppose the idea of liberty and equality for all people,

opponents of Radical Reconstruction created a myth about it — that it

was a cynical ploy by unscrupulous Northern whites to maneuver

ignorant blacks into political power and then use that power themselves

to control and plunder the South. Historians, out of a similar

prejudice against blacks, confirmed the myth as fact.

The myth, and the bogus historiography that seemed to confirm it, tried

to disguise an opposition to equality for blacks, but the disguise

comes apart in The Birth Of A Nation, where attempts by blacks to

interact on terms of social equality with whites are presented as

outrages almost on a level with political and judicial corruption.

Henry Walthall's Little Colonel grows steely-eyed when black soldiers

assert their right to walk on the sidewalk in front of his house, when

Silas Lynch offers to shake his hand — his look in those moments is

not so different from the chilling one he gives in reaction to the

death of his sister at the hands of a crazed black would-be rapist.

Earlier, that same sister had reacted with a look of repugnance when

Stoneman's daughter publicly conversed, on perfectly innocent and civil

terms, with the mulatto Lynch.

In such attitudes we see the ugliest side of casual environmental

racism — the nastiness it could provoke when its assumptions were

challenged by “uppity” blacks . . . that is, blacks who presumed to be

entitled to the common respect and dignity accorded to whites.

Indeed, the pathological racism of The Birth Of A Nation can be seen

as a kind of justification for this nastiness, by showing where such

presumption by blacks will inevitably lead — to sexual assaults by

black males on white females, to miscegenation.

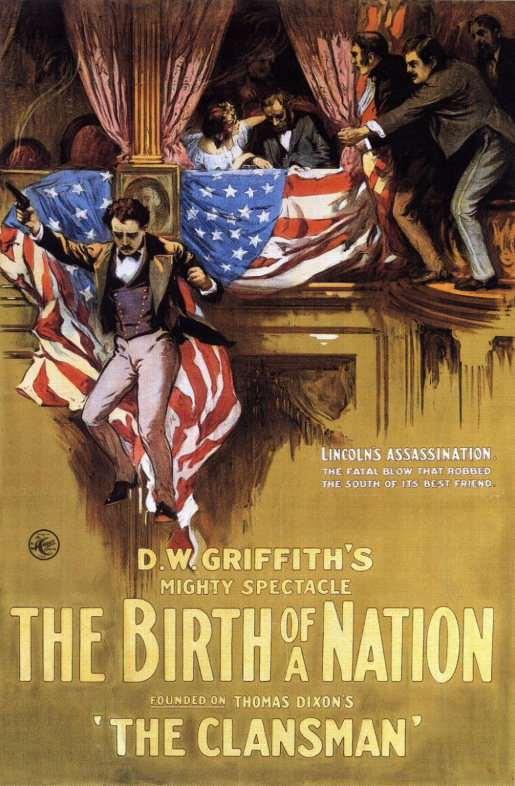

This connection is established in the very first scenes of the second

half of the film. In the wake of Lincoln's death and Stoneman's rise

to greater power, Stoneman's maid has now become his social equal,

dressing like a lady and insisting on being treated as one by

Stoneman's associates, though she remains an infantile schemer.

Stoneman states his intention of elevating his protege, the mulatto

Lynch, to full equality with whites — but we are shown what the

consequences of this will be, which Stoneman can't see yet. Lynch

stares lustfully at Stoneman's daughter, foreshadowing his future

pursuit and attempted rape of her. That's what “equality” means to him.

The association of political and social equality for blacks with sexual

designs by black males on white women is carried through the scenes in

South Carolina which follow. We see blacks displaying signs which read

“Equal Rights/Equal Politics/Equal Marriage.” The

drumbeats are clear — the progression apparently inevitable. In the

black-dominated state legislature, the

ignorant, buffoonish black members react with indifference to the

government business being conducted, until a bill allowing

miscegenation is passed, whereupon they direct sexual leers at the

white women in the galleries and then break out in riotous celebration.

A title informs us that this picture of a black legislature was based

on historical photographs, but David Shepard, in his excellent short

documentary on the making of the film, included in the Kino DVD

edition, reveals that it was not — it was based on political cartoons

of the time. Once again, when Griffith wants to inject an element of

psycho-sexual paranoia into his film he adopts a different standard of

historical accuracy than he applies elsewhere.

Black political power is shown as having no legitimate ambitions. It

exists only to enrich or enable the white and/or mulatto manipulators

of the black vote, and to sanction sexual relations between the races.

Even “marriage” is a euphemism here, since blacks are shown as having

no conception of the institution — it just represents a license to

copulate, with or without the woman's consent.

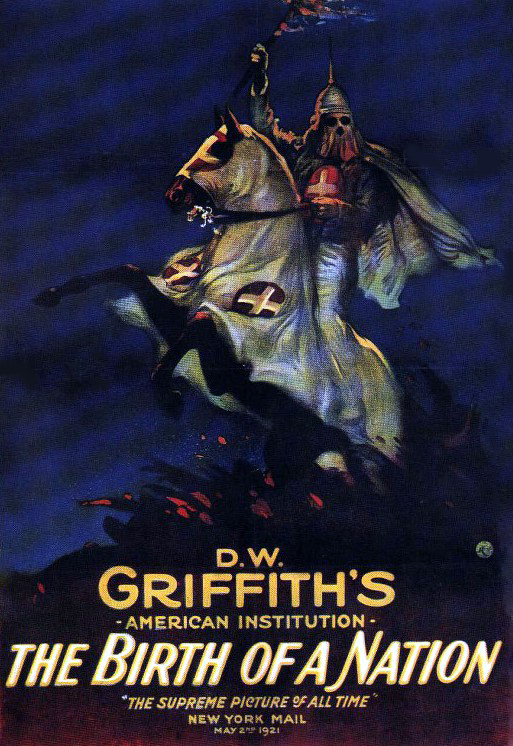

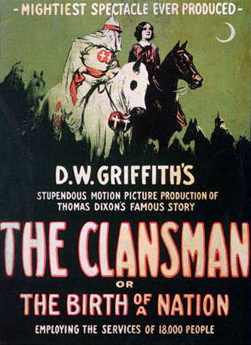

The rise and mobilization of the Klan is presented as a response to the

political and judicial corruption of Southern society by the wicked

carpetbaggers and their ignorant black minions, but its primary

dramatic function is to avenge Gus's attempted rape of the Little

Sister

— by murdering him extralegally — and to save the other white female

principals from attempted rape. Everything, in the end, boils down to

protecting white females from sexual outrages by black males.

In the finale, as former Union and Confederate soldiers and

their women huddle in a remote cabin assaulted by crazed blacks, we

are told that they have united, not in defense of shared American

values, shared ideals of justice and freedom, but “in defense of their

common Aryan birthright”, granted by the “purity” of their Aryan blood,

which is really what is threatened here. The women face the

possibility of rape by the animalistic blacks and the men prepare to

kill them rather than allow that possibility to come to pass. The

“nation” whose birth this film celebrates has almost nothing to do with

the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution — everything to do

with Aryan purity and superiority. It's racist to the core.

The white sheets of the Klansmen in The Birth Of A Nation do not

cover idealists riding to right political and judicial wrongs, despite

a blizzard of intertitles which tell us otherwise. They cover the

beleaguered psyches of 20th-Century males riding to restore their own

insecure manhood.