. . . to think about Marilyn Monroe.

Monthly Archives: May 2007

NOIR, NOT NOIR: LAURA

Film noir

is sometimes used as a catch-all phrase to designate any film from the

1940s or 1950s which has moody black-and-white photography, snappy,

cynical dialogue and some sort of crime element in its plot. In

the process, the term becomes too vague to be really useful.

Gritty underworld crime dramas have been with us since the early silent

era, as has moody expressionistic cinematography, and the private-eye

murder mysteries of the early 40s had plenty of snappy, cynical

dialogue. But the true film noir

didn't emerge until after WWII and it brought something new to

Hollywood cinema — a comprehensive vision of the modern world as a

dark, hopeless place, morally compromised at its core.

Underworld crime dramas could be dark, but they always imagined forces

of order and decency ready to do battle with and overcome the forces of

chaos and destruction. The private eye, for all his cynical talk,

had a kind of nobility and honor that he carried with him into the

shadowy realms in pursuit of truth and rough justice.

Traditional crime dramas and police or agency procedurals continued on

into the post-war era, as did murder mysteries, and though they became

inflected with the atmosphere of true films noirs they didn't stake out quite the same territory.

Laura, made during WWII, is

one of the most stylish and diverting entertainments ever concocted in

Hollywood, and it's regularly classed as an early film noir

— but it's nothing of the kind. The film believes in romance and

love, in the triumph of justice and the possibility of knowing the

truth about things. In a genuine film noir this sort of faith has been lost.

Still, one can see themes emerging in Laura which will play out more forcefully in film noir.

Laura, the film's title character, is an unusually strong and

self-reliant woman, emotionally and financially independent. She

destroys a weak man who loves her but can't win her — as does the femme fatale of the post-war noir

tradition. But Laura's strength is seen as a positive thing here,

not as an insidious threat, and there's a red-blooded man on the scene

who can match her strength.

In the post-war noir,

something goes wrong with the whole idea of the red-blooded man, who suddenly

seems inadequate to the task of engaging a corrupt world or matching

the strength of a self-possessed woman. The world, and desire

itself, come to seem like streets that dead-end in disaster and

oblivion. Some lines from Two Noble Kinsmen, probably by Shakespeare, who co-wrote the play with John Fletcher, anticipate the realm of the film noir nicely:

This world's a city full of straying streets,

And death's the market-place where each one meets.

SIDESHOW

The amazing object above is an 18″ statuette of the Bride Of Frankenstein made by Sideshow Collectibles.

Sideshow

started out as a model and miniature shop for the film business, with a

sideline in design and sculpting for toy companies. Back in the late 90s, Sideshow

decided it could make better toys, and have more fun, if it got into manufacturing and

so started its own line of 8″ figures of characters from the classic Universal

horror films.

My sister,

shopping for toys for her kids one day, ran into the really

extraordinary 8″ figure they made based on the monster from The Son Of

Frankenstein. She thought I would like it and bought me

one. I loved it — thought it was head and shoulders above other

Universal figures I'd seen, with its first-rate sculpting and its

attention to details in the acccessories. It became one of my

prize possessions — one of my penates, my household gods.

A lot of other

people felt the same way — the 8″ line sold incredibly well and

inspired the company to get more ambitious. I'd checked out the

other 8″ Universal figures but only really liked the bride from The Bride Of Frankenstein. The first 12″ Sideshow figure I saw blew me away, though — Lon Chaney's Erik, from The Phantom Of the Opera,

in his Masque of the Red Death costume. (See it here.) It

remains one of the greatest 12″ action figures of all time.

Again, it was my sister who discovered it and bought it for me.

Tragically, I discovered that almost everything Sideshow produced in

the 12″ format was brilliant. I started collecting them

feverishly. They would sell out quickly in retail establishments

and on Sideshow's web site, so I had to track many down on eBay.

The success of the 12″ line, which came to include historical

figures as well as characters from TV shows, led Sideshow to up the

ante again with their 18″ line. These were not fully articulated

action figures. Sometimes they had slightly posable wire

armatures, sometimes they were cast fully in polystone. The best

of them — like the vampire from Murnau's Nosferatu — were real works of art.

They were so expensive that, sadly, I had to get more

selective. I couldn't resist the 18″ Bride, figure, though.

She's just amazing.

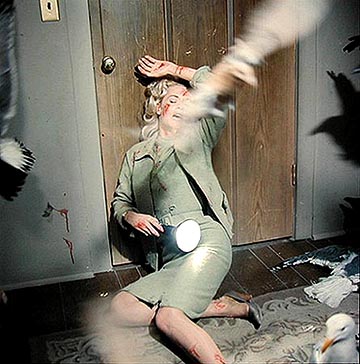

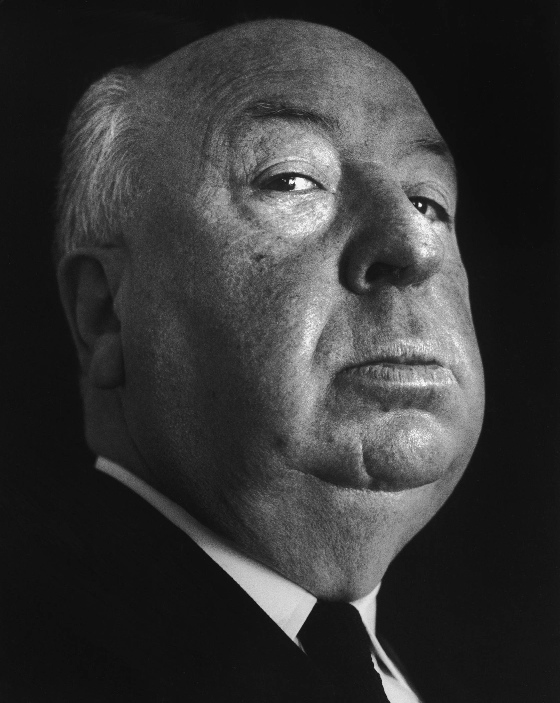

CAMILLE PAGLIA ON ALFRED HITCHCOCK

“Space is like an opaque medium that Hitchcock knows how to carve, trim and slice as if it were a side of beef.”

This is from Paglia's book-length essay on The Birds

— and what she says of Hitchcock is true of all the great directors,

who carve up and reshape space before our eyes, drawing us ever deeper into the

spatial illusion of the cinematic image, the core of its sensual appeal and the

primary medium of its emotional expressiveness. This malleability

of space, its ability to be carved and reshaped in cinema, is what places cinema squarely among the plastic arts.

It's a hard concept to grasp, which is why film is traditionally

analyzed in terminology derived from the visual arts, like painting, or

the literary arts, like theater and the novel, even though its most

powerful effects more closely resemble those of sculpture, architecture

and dance. Albert Einstein said, “Space is not merely a

background for events, but possesses an autonomous structure.”

Film does not simply create occasions for visual or literary events — it investigates the structure

of space, associates the structure of space with the structure of

dreams. Orson Welles said that on some level every great film is a chase — which is

just another way of saying that on some level every great film is about space.

[Paglia's short book on The Birds,

published as part of the BFI Film Classics series, doesn't, to me, get

at the heart of the film's themes, but it's an exhilarating

intellectual tour de force

with a dazzling range of allusions to other works of art and to the

cultural matrix from which the film emerged. It's an

indispensable text.]

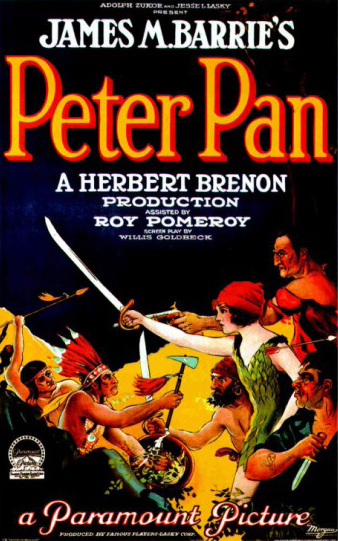

PETER PAN (1924)

The first half hour of Herbert Brennon’s Peter Pan is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking, masterful in a delicate and unusual way.

Almost all of it takes place in the Darling nursery, on a set that is shot

from basically one angle and seems designed to suggest a theatrical

stage. I’m guessing that this was a deliberate strategy, meant to

associate the film with the celebrated stage productions of Barrie’s

play, even though it was somewhat anachronistic for a film from 1924. Brennon,

however, has taken this limitation as a challenge, and in his own

subtle way has mastered it.

The long shots of the set, with a frame that seems to mimic a proscenium

arch, are lit with extraordinary care by James Wong Howe. He achieves a

stunning impression of depth in the way his lights define discrete

spaces within the room and sculpt individual figures within those

spaces. Brennon’s choreography of movement within the constricted

location reinforces the stereometric nature of Howe’s lighting.

Slowly, and with great subtlety, Brennon allows his camera to tentatively

explore this space from slightly different angles — almost like a

tease. We never feel that our general sense of watching a stage play is

challenged — but seem suddenly, briefly transported up onto the stage

for a privileged view of the action, as in a dream.

The lighting shifts progressively throughout the sequence in a decidedly

expressionistic way — from the high illumination of the opening to the

more atmospheric shadows of the room lit by the nightlights. Then Peter

appears, and the gears shift radically. Wendy sews Peter’s shadow back

on in a gorgeous half-silhouette downstage, then Peter dances with his

shadow in a circle of light, shot from slightly above, that seems to

have no logical source.

When Peter teaches the Darling children to fly, our head-on view of the set

is explicitly violated as we see one of the boys flying up towards a

camera placed near the ceiling and shooting in a near-reverse angle to

the one we’ve mostly been watching from. It’s a shocking and magical

shift — echoing the shock and magic of the child’s first flight.

Alas, the rest of the film, in Never Land, is not as magical as this first

act. The Catalina locations, the studio forest and underground lair,

the actors in animal costumes and the actors in human costumes never

quite cohere into a vision, despite many delightful passages. The final

action sequence on the pirate ship is confused and dull — until the

wondrously choreographed sword battle between the Lost Boys and the

pirates lifts it all into magic once again.

The special effects vary in quality, too. Most of the wire-work flying is

well done, but the flight of the pirate ship at the end is

underwhelming, and some of the superimpositions involving Tinkerbell

are poorly executed.

This is a title-heavy film, but the titles are faithful to Barrie’s truly

charming text, tastefully selected and arranged.

The general result is a very uneven but endlessly fascinating film.

Brennon’s vaguely perverse sensibility, always delivered with a

gossamer touch, is evident most especially in his use and appreciation

of Betty Bronson in the title role. She dances the part in a frankly

sensual way, and she is unmistakably and delightfully female — which

allows Brennon to exploit an unmentionable eroticism in certain

passages.

The half-silhouetted shadow-sewing sequence between Wendy and

Peter has the quality of a sexual encounter, and there is nothing

innocent in the numerous kissing scenes — between Bronson and Mary Brian,

Bronson and Anna Mae Wong, Bronson and Esther Ralston.

When Peter lies down to sleep on the leaf bed after Wendy and the Lost Boys have left the underground lair, Bronson is photographed in a languorous and sensual and purely

feminine pose — which gives Captain Hook’s spying on her a wholly different spin than the narrative might suggest. Hook’s hatred of Peter reads as thwarted lust, pure and simple. He knows as well as we do that the creature on that bed is a woman.

Sex in silent movies was a lot more interesting than it is in movies today.

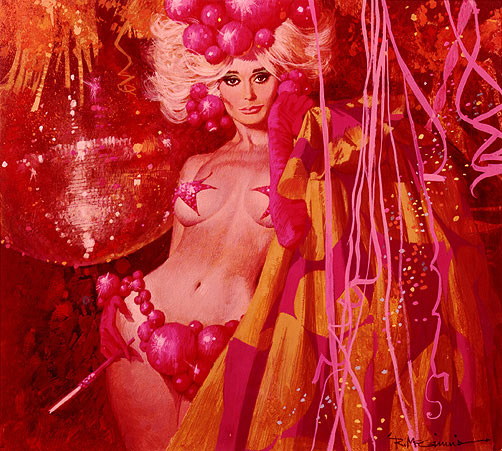

A MCGINNIS FOR TODAY

Here’s Robert McGinnis‘s evocation of a Vegas showgirl. A master of paperback cover art for pulp fiction, McGinnis got the point-of-sale appeal of such covers down to a science. I’d buy whatever book this painting graced the cover of, even though I knew in my heart that it would never live up to the image’s promise.

MEXICO AND FILM NOIR

Mexico has always had a peculiar place in the popular American imagination.

It has generally tended to represent a kind of mirror world where the

subconscious could emerge into the light — where desire, fear, death, despair, escape from responsibility and propriety could show themselves plainly.

There is chauvinism involved here, of course, a sense of Mexico as a

primitive country, but also an appreciation of the positive genius of Mexican

culture, its sensuality, its frank engagement with death and violence,

with things that the official culture of America prefers to keep hidden

in the shadows.

WWII exposed those hidden things for a generation of Americans and in its wake film noir began a systematic investigation of the shadow world at the fringes

(and somehow also at the heart) of American culture. In the

process, Mexico took on a new aura. It became a kind of shimmering

paradise, the locus of an honesty and innocence that no longer seemed

feasible along the mean streets and lost highways of post-WWII America.

So in Out Of the Past, Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer live out a doomed idyll in Mexico, on the run from a gangster who has his hooks into both of them. When they try to carry that idyll north of the border, integrate it into a new life there, they’re both destroyed.

In Border Incident, decent Mexican peasants are exploited and sometimes murdered by powerful American businessmen north of the border who traffic illegally in their labor. (Border Incident, while it deals with a number of themes from classic film noir, departs from the tradition by positing good-guy government agents as saviors of the peasants, thus violating the cosmic cynicism and skepticism of the true film noir.)

In Gun Crazy, the young couple possessed by a mad love, a love fuelled by irrational violence, are just a few hours away from a safe passage over the border when their crimes catch up with them and send them on a final hopeless flight from retribution and death.

The nuttiest use of Mexico in film noir can be found in what may be the nuttiest of all films noirs, His Kind Of Woman. The movie starts off fairly traditionally, with Robert Mitchum as a down-on-his-luck gambler who’s hustled into taking a mysterious job south of the border. As soon as he arrives in Mexico it’s like he’s gone to Oz. He walks into a dingy cantina about the size of a phone booth and in a back room, about half the size of a phone booth, he finds Jane Russell singing Five Little Miles From San Berdoo accompanied by two Mexican musicians doing cool jazz riffs on guitar and piano. Things get so nutty after that that the whole noir genre is pretty much deconstructed by the time it’s all over.

As film noir played itself out in the 50s, the image of Mexico in American art shifted back to a more familiar form. In the Tennessee Williams play The Night Of the Iguana (and in John Huston’s film adaptation of it), in Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head Of Alfredo Garcia, in Huston’s film of Under the Vocano, Mexico became once more a portal of Hell, where lost American souls went to confront their demons — in an unequal contest which the demons were always fated to win.

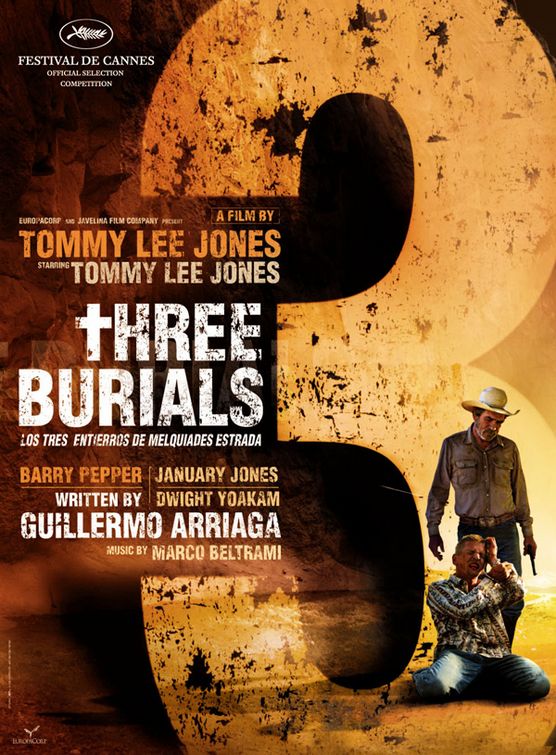

In the light of this peculiar history, it’s interesting to look at a recent film, the post-modern film noir The Three Burials Of Melquiades Estrada. There another troubled American soul heads south of the border on a quest for a lost paradise — only to discover that the paradise wasn’t really lost because it never really existed. And it doesn’t matter. We realize by the end that the quest itself has redeemed and saved him. The film was written by a Mexican, who knows that Mexico is neither Paradise nor Hell . . . except in the dreams of lost souls on both sides of the line.

[For more thoughts on Mexico and film noir go here.]

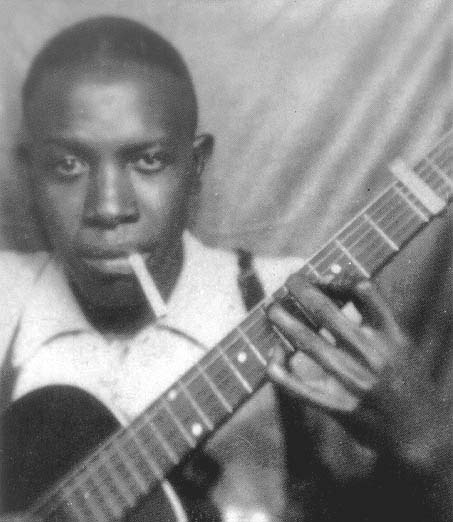

THE CIGARETTE POLICE

Above is one of the few authentic photographs of Robert Johnson, the

great blues artist. Having allegedly made a bargain with the

Devil to acquire his almost supernatural musical gift he was probably

not too worried about the health effects of

smoking, but others are worrying on his behalf — and yours. A

U. S. postage stamp made from the photograph removed the cigarette from

his mouth.

Robert Johnson paid for this photobooth portrait, and

this was how he chose to present himself before the camera's eternal

gaze, with the haunted eyes and the spidery fingers on the frets of his

guitar and the cigarette dangling from his lips. I wonder if the

bureaucrats who decided to alter his image of himself ever really

listened to his music — ever realized that the hellhounds on Robert Johnson's trail were also on theirs.

Below is a link to a Boing Boing post about the removal of cigarettes from historical images of literary and pop culture

figures:

The Cigarette Police

As

a kid I remember being horrified to learn that the Soviet government

would rewrite the “factual” content of encyclopedias to reflect the

current political climate. Now Western governments and corporate

entities (like there's a difference between the two) are tidying

up history to reflect current policies of social hygiene.

You

may see a big difference between these two forms of historical

revisionism but the phenomena are intimately related in principal —

both involve large state and corporate interests appropriating history and

changing it at will. They are, in other words, staking a claim to the

ownership of history, and by extension reality.

THOMAS CARLYLE ON ALFRED HITCHCOCK

Actually, this is Carlyle (pictured below) on Dickens, but the application to Hitchcock is clear enough:

“. . . deeper than all, if one has the eye to see deep enough, dark,

fateful, silent elements, tragical to look upon, and hiding amid

dazzling radiances as of the sun, the elements of death itself.”

Dickens and Hitchcock both hid within the conventions of popular art,

and one misses a lot, one misses close to everything, if one takes

their disguises too literally.

EL TACO FRESCO

About a five minute walk from my house is a little mini-mall with a

taco shop that serves the best tacos in Vegas, by far — the best

carnitas tacos I've ever had anywhere. The carnitas is tender but

has crispy, charcoal-flavored edges — the fried fish in the fish tacos

is fresh and moist but crunchy on the outside. The tacos are two

bucks apiece and two

of them make a fine meal.

The shop opens onto a dingy dive bar next door where they'll serve the

food and where you can smoke and drink. The bar and the shop are

both open 24/7. The weirdest people in the world go there, so I

feel right at home.

It's my new favorite joint in Vegas.

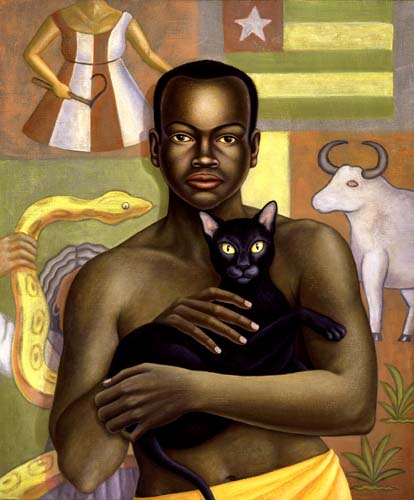

A CREHORE FOR TODAY

In this imaginary portrait of a boy from Togo, Amy Crehore plays with

space in an interesting way. The low relief of the central figure is

accentuated by placing him against a flat wall decorated with flat

images. It's as though he's emerging from the surface of the

wall, entering space, tentatively.

A CLOWN FOR TODAY

This image of a clown is from a 1900 calendar for the Antikamnia Chemical Company. (Thanks to Boing Boing for the link.)

Many people are terrified of clowns — this one can only add to their nightmares.

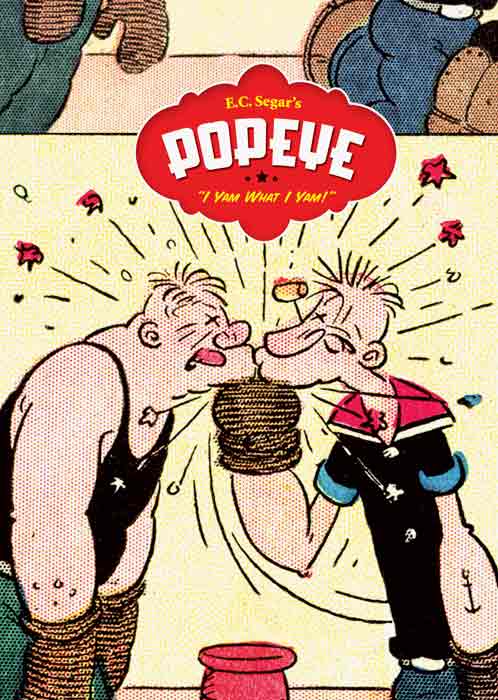

POPEYE

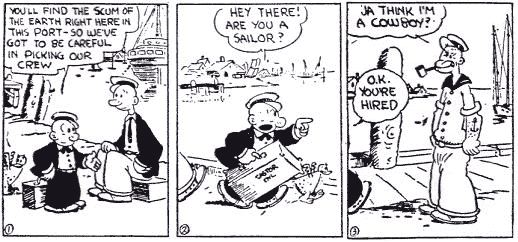

One day in 1929 a peripheral character popped up in a panel of E. C. Segar’s newspaper comic strip Thimble Theater and proceeded to take it over. His name was Popeye. Below — his first appearance:

Thimble Theater started out as a parody of popular melodrama, but neither parody nor melodrama could contain the anarchic imagination of Segar. His world was invaded

by supernatural elements, did not conceive of drawing clear distinctions between good and evil, and relished too plainly the energy of rambunctious physical violence. It was rather closer in spirit to The Iliad than to The Perils Of Pauline.

Popeye at once seemed to offer a kind of sea anchor to Segar’s roiling, restless

sensibility. Popeye was ever ready to dispense violence, in his

practical, unemotional way — as just another job, like hauling

anchor. He’d obviously been around the world a few times —

nothing surprised him, or at least not for long. He was never

heroic but always useful (a far cry from the righteous protagonist he later

became in the Fleischer animated cartoons.)

Seen through Popeye’s eyes, Segar’s world made sense — or rather its lack of sense didn’t seem too disturbing. With Popeye at the helm, Thimble Theater sailed

on its eccentric way until Segar’s death in 1938, becoming one of the great, dark comic

works of American culture. Popeye was eventually toned down and conventionalized as his adventures became addressed more and more to kids, but the real character is now available once again in a series of reprints of the original comic strip being issued by Fantagraphic books.

In well-printed, oversized volumes, the first of which is now out, we

can encounter him as he was — part Odysseus, part Achilles . . . the

eye of a perfect existential storm.

INTOLERANCE

In order to enjoy and appreciate Intolerance you have to watch it the

way you read Dickens — submitting to its rhythms, surrendering to its

asides and narrative diversions. You simply can’t be too

impatient to find out what happens next in the story (or

stories.) Dickens and Griffith are more interested in how things

happen, where things happen, to whom things happen. There’s no

shortage of fascinating incident in either artist’s work, and much of

it is spectacular — but sometimes the incidents are very small indeed,

and no less fascinating for that.

I’ve seen Intolerance many times, and I find I remember small gestures and

glances, brief passages of body language with the same vividness that I

remember great lines of dialogue from talking films. The flirty

and then dismissive looks the girl outside the dance hall gives the

mill owner Jenkins who’s come to spy on his workers make for an

indelible moment — involving a bit player we never see again.

The Mountain Girl’s postures of energy and defiance look in retrospect

like a primer on flapper attitude, years before the flapper even

existed.

It takes Griffith over half an hour to introduce us to all four of the time

periods covered in the film. We start in the modern story,

proceed to the time of Jesus, then to 16th-Century France — then back

to the modern story before seeing the walls of Babylon for the first

time.

Almost every image in this first half hour is stunning, worth studying for its

dynamic composition involving movement and deep space. The illusion of

depth draws us emotionally into the film just as surely as the

interwoven narratives and the performances.

This effect is most powerful on a big screen, of course, but it’s effective enough on

a decent-sized TV monitor. When you consider a video screen’s

tendency to flatten any image, it’s all the more amazing that

Griffith’s images retain their stereometric brilliance in that format.

One great virtue of the DVD format is that it allows one to watch (or, one hopes,

re-watch) a film like Intolerance in segments — which is the way one

reads those long Victorian novels originally published serially.

The film reveals much when experienced this way. There’s almost

no chance in any continuous viewing of the three-plus hours of Intolerance that one could sustain the intensity of attention needed

to fully absorb its torrent of beautiful images in detail.

If you have Intolerance on DVD, go watch just its first half hour — to the end

of the first Babylonian segment. There’s enough cinematic

brilliance in that half hour to justify, by itself, the whole medium of

movies.

[If you don’t have Intolerance on DVD rush out and get it immediately. The

Kino edition is generally considered to have the best image quality.]

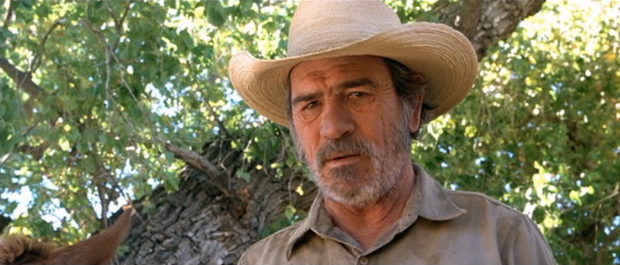

THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA

Tommy Lee Jones, one of the great actors of his generation, has, with this

film, become one of the most important contemporary directors.

It’s just miraculous. The wonderful performances by the ensemble

cast and by Jones himself might have been expected — but the brilliant

script and the brilliant filmmaking testify to a sensibility at home within the whole range of cinematic expression.

The sense of place that the film communicates, via Chris Menges’s stunning

cinematography, reminds one of John Ford. Jones, like Ford when

he was shooting in Monument Valley, is working here in a landscape he

clearly loves and knows well. It’s important to him, as it was to

Ford, to make us feel what it’s like to be in and move through that

landscape — and he does.

One notes with particular pleasure Jones’s use of horses in the film. Just watching Jones

sit a horse brings back by itself the whole tradition of the American

Western, in which horses aren’t props but a means of establishing the

authority and conveying the subtler nuances of character. The horses themselves are

given their own moments — all memorable. We see a steady old cow

horse try (successfully) to master its hysteria as a man fires a rifle

next to its head. We see a horse react emotionally as another

horse rides off into the distance — violating the compact of the herd

instinct. It reminds me a bit of Tolstoy, another serious

horsebacker, who always lets you know how the horses in his scenes are

feeling.

The tale Jones tells, written by Guillermo Arriaga, the author of Amores Perros, is

dark, comic and moving. It’s set on the Texas border and asks us

to travel imaginatively backwards on the route of the illegal

immigrants — to enter into the memories and dreams the immigrants leave

behind, and so see them more fully as human beings, as opposed to mere

statistics.

The tale is inflected with the sardonic, broadly comic Mexican view of death — Posada’s calaveras ride with Jones here — and the film’s visuals reflect the bold colliding colors of Mexican folk art, all blended seamlessly with the shabby commercialism of American

culture that also defines the world of the border lands — what Carlos

Fuentes calls Mexamerica, in many respects a nation unto itself, which

no wall will ever cut in half, just as no wall could ever really cut Germany

in half.

As in Ford’s great films, the landscape itself finally subsumes human contradiction

and tragedy — infuses a sense of transcendence which expresses itself

as hope. Irrational gringo optimism and sardonic Mexican resignation transform each

other, merge into one deeply humane vision.