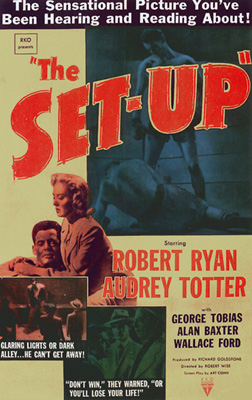

The Set-Up, a classic film noir directed by Robert Wise in 1949, couldn't be more different in many ways from Jacques Tourneur's equally admired classic noir Out Of the Past. For one thing, The Set-Up doesn't have a femme fatale. There's no romance, no glamor, no witty hardboiled repartée. But if you realize that classic film noir is centrally concerned with anxiety and neurosis about manhood, the two films fit neatly together in the noir tradition.

The Set-Up

is about the boxing underworld, the tank-town circuit where

up-and-comers get their chops and has-beens rent themselves out as

human punching bags. Robert Ryan plays a has-been, a

once-promising fighter who's come to the end of the line. His métier is perhaps the most iconic arena for displays of traditional virility — his exhaustion a sharp symbol of its decline.

The fans jeer him. His own manager takes money to get him to take

a dive but doesn't even bother to inform him, so sure is he that his

fighter is going to lose . . . one more time. Ryan's

long-suffering wife is about to walk out on him, unable any longer to

watch his steady and inexorable collapse. Ryan's continued belief

in himself as a fighter is presented as the delusion of a punch-drunk

loser.

But Ryan still has one more victory in him, one last assertion of his

potency in the ring. The victory, however, is no triumph.

His wife hasn't even come to the arena to watch it. His corner

men flee before the fight is over. The manager of the fighter he

was unknowingly paid to lose to sets his thugs on him and beats him up

in an alley, smashing his hand so he can never fight again.

In a powerful sequence just before the assault in the alley, Ryan runs

through the empty arena, past the empty ring, trying to escape.

His ritual of manhood has become a shadowplay that nobody cares about,

nobody's watching.

The Set-Up

plays out in real time over the course of one night, creating an almost

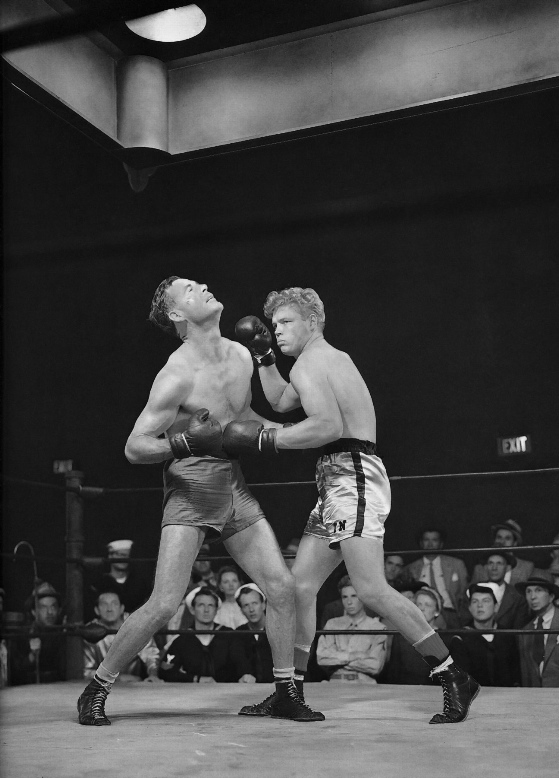

unendurable suspense. The four rounds of boxing shown, again in

real time, are the best evocation of a real fight ever put on

film. The high-speed meta-narrative that always develops in a real fight,

especially a good one, is both complex and legible, and the combat is

convincingly brutal. (Ryan was a champion fighter at the college

level and knew what he was doing.)

The ending of the film is satisfying because of the heroism involved in

Ryan's last stand — even though it's meaningless in practical

terms. It's sort of a glorious farewell to his own construction

of himself as a man. His wife is still there for him, happy that

he's been forced to move on. But move on to what?

Film noir never had an answer

to that question, and the resulting tension is what has always constituted the

deep subliminal appeal of the genre. It posed a question that

modern men are still asking themselves.