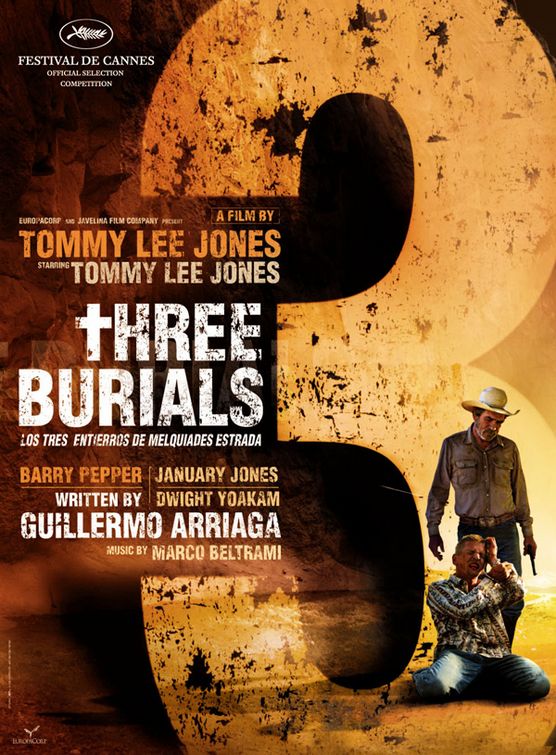

Tommy Lee Jones, one of the great actors of his generation, has, with this

film, become one of the most important contemporary directors.

It’s just miraculous. The wonderful performances by the ensemble

cast and by Jones himself might have been expected — but the brilliant

script and the brilliant filmmaking testify to a sensibility at home within the whole range of cinematic expression.

The sense of place that the film communicates, via Chris Menges’s stunning

cinematography, reminds one of John Ford. Jones, like Ford when

he was shooting in Monument Valley, is working here in a landscape he

clearly loves and knows well. It’s important to him, as it was to

Ford, to make us feel what it’s like to be in and move through that

landscape — and he does.

One notes with particular pleasure Jones’s use of horses in the film. Just watching Jones

sit a horse brings back by itself the whole tradition of the American

Western, in which horses aren’t props but a means of establishing the

authority and conveying the subtler nuances of character. The horses themselves are

given their own moments — all memorable. We see a steady old cow

horse try (successfully) to master its hysteria as a man fires a rifle

next to its head. We see a horse react emotionally as another

horse rides off into the distance — violating the compact of the herd

instinct. It reminds me a bit of Tolstoy, another serious

horsebacker, who always lets you know how the horses in his scenes are

feeling.

The tale Jones tells, written by Guillermo Arriaga, the author of Amores Perros, is

dark, comic and moving. It’s set on the Texas border and asks us

to travel imaginatively backwards on the route of the illegal

immigrants — to enter into the memories and dreams the immigrants leave

behind, and so see them more fully as human beings, as opposed to mere

statistics.

The tale is inflected with the sardonic, broadly comic Mexican view of death — Posada’s calaveras ride with Jones here — and the film’s visuals reflect the bold colliding colors of Mexican folk art, all blended seamlessly with the shabby commercialism of American

culture that also defines the world of the border lands — what Carlos

Fuentes calls Mexamerica, in many respects a nation unto itself, which

no wall will ever cut in half, just as no wall could ever really cut Germany

in half.

As in Ford’s great films, the landscape itself finally subsumes human contradiction

and tragedy — infuses a sense of transcendence which expresses itself

as hope. Irrational gringo optimism and sardonic Mexican resignation transform each

other, merge into one deeply humane vision.