My nephew Harry just acquired his 100th 12″ action figure. I’ve got a shockingly large number of them myself. Some people, though, take their fascination with these toys to surreal lengths.

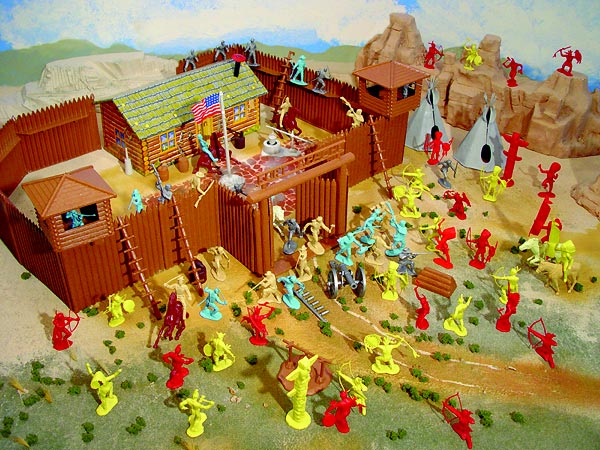

The photo above is just part of a huge diorama using customized 12″ figures and fabricated in-scale props. It takes me back to the days of my youth when I used to disappear into the minature worlds of toy-figure playsets, like the Fort Apache set I got when I was five or six:

Wanting to possess whole little worlds like this and enter into them imaginatively is closely connected to wanting to make movies, which accounts for the fascination of 12″ figures taken from characters in movies — transported back, as it were, into the miniature realm where they had their imaginative birth.

Monthly Archives: May 2007

POP ART

It drives me crazy when people talk about works of Pop Art as though

they somehow belong in the same category as traditional high art — as

though it makes any sense at all to talk about the oeuvre of Andy Warhol in the same breath as the oeuvre

of Jan Van Eyck, just because they tend to be grouped that way by the academy

and by art institutions. I actually think it's a sign of clinical

insanity, culturally speaking.

But that doesn't mean that works of Pop Art aren't unspeakably cool. The Lichtenstein above is unspeakably cool.

THE SET-UP

The Set-Up, a classic film noir directed by Robert Wise in 1949, couldn't be more different in many ways from Jacques Tourneur's equally admired classic noir Out Of the Past. For one thing, The Set-Up doesn't have a femme fatale. There's no romance, no glamor, no witty hardboiled repartée. But if you realize that classic film noir is centrally concerned with anxiety and neurosis about manhood, the two films fit neatly together in the noir tradition.

The Set-Up

is about the boxing underworld, the tank-town circuit where

up-and-comers get their chops and has-beens rent themselves out as

human punching bags. Robert Ryan plays a has-been, a

once-promising fighter who's come to the end of the line. His métier is perhaps the most iconic arena for displays of traditional virility — his exhaustion a sharp symbol of its decline.

The fans jeer him. His own manager takes money to get him to take

a dive but doesn't even bother to inform him, so sure is he that his

fighter is going to lose . . . one more time. Ryan's

long-suffering wife is about to walk out on him, unable any longer to

watch his steady and inexorable collapse. Ryan's continued belief

in himself as a fighter is presented as the delusion of a punch-drunk

loser.

But Ryan still has one more victory in him, one last assertion of his

potency in the ring. The victory, however, is no triumph.

His wife hasn't even come to the arena to watch it. His corner

men flee before the fight is over. The manager of the fighter he

was unknowingly paid to lose to sets his thugs on him and beats him up

in an alley, smashing his hand so he can never fight again.

In a powerful sequence just before the assault in the alley, Ryan runs

through the empty arena, past the empty ring, trying to escape.

His ritual of manhood has become a shadowplay that nobody cares about,

nobody's watching.

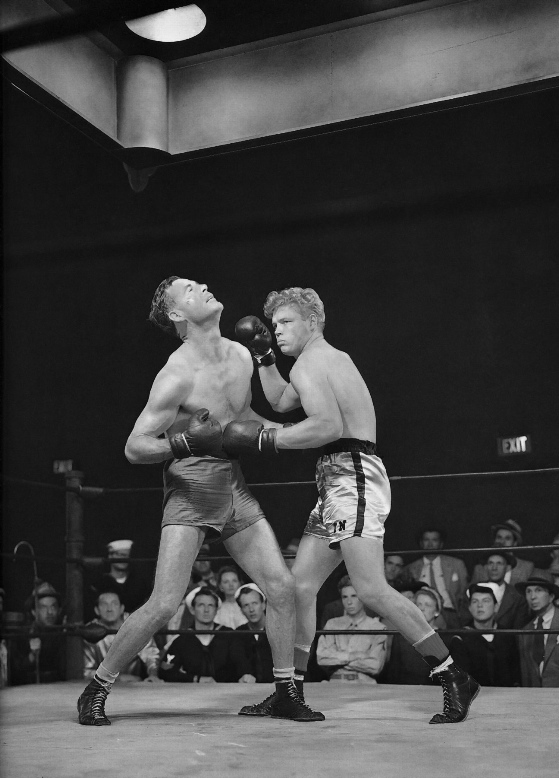

The Set-Up

plays out in real time over the course of one night, creating an almost

unendurable suspense. The four rounds of boxing shown, again in

real time, are the best evocation of a real fight ever put on

film. The high-speed meta-narrative that always develops in a real fight,

especially a good one, is both complex and legible, and the combat is

convincingly brutal. (Ryan was a champion fighter at the college

level and knew what he was doing.)

The ending of the film is satisfying because of the heroism involved in

Ryan's last stand — even though it's meaningless in practical

terms. It's sort of a glorious farewell to his own construction

of himself as a man. His wife is still there for him, happy that

he's been forced to move on. But move on to what?

Film noir never had an answer

to that question, and the resulting tension is what has always constituted the

deep subliminal appeal of the genre. It posed a question that

modern men are still asking themselves.

T. S. ELIOT ON ALFRED HITCHCOCK

Well,

not precisely, but this quote by Eliot about poetry offers a key to

analyzing Hitchcock's films, and, indeed, all great suspense thrillers:

“The chief use of the ‘meaning’ of a poem, in the ordinary sense, may

be . . . to satisfy

one habit of the reader, to keep his mind diverted and quiet, while the

poem does its work upon him: much as the imaginary burglar is always

provided with a bit of nice meat for the house-dog.”

In Hitchcock's movies, the plot mechanics, the mystery to be solved, the suspense engendered

by the nominal physical jeopardy of the characters — all this belongs

to the territory of the “maguffin”, the essentially arbitrary device

that sets the narrative in motion.

The truth of the film is experienced on another level — which is one

reason it's so enjoyable to watch Hitchcock's movies over and over

again, why they always seem new. You forget the plot mechanics instantly —

they don't linger in the mind for even a moment after the film is over. All you're

left with is the memory of confronting, and surviving, some nameless,

existential dread.

[I am indebted to Ken Mogg's The Alfred Hitchcock Story for pointing me towards the Eliot quote and suggesting its connection to the Hitchcock maguffin. The Alfred Hitchcock Story

is a pictorial survey of Hitchcock's films with pithy commentary by

Mogg and other Hitchcock experts. It's worth tracking down the

British edition, published by Titan Books, since the American

edition is unfortunately and unaccountably abridged.]

MERRY-GO-ROUND

Erich Von Stroheim was above all else a wondrous spinner of tales. His

storytelling mode was, at heart, melodrama, but much modified from its

conventional forms. He embraced all the sensational elements of melodrama, its

reliance on wild coincidence and its stark dynamic of good versus evil

but subverted them to his own ends. He made the erotic subtext of much

melodrama explicit, he used coincidence to serve his own fatalistic

vision of human destiny, and he inverted expectations about protagonist

and antagonist, making the former often weak and foolish and the latter

invariably fascinating and appealing, especially when he himself played

the role.

His

vision of the world was brutal and harsh, but he preserved the romance

and the celebration of virtue at melodrama's core — in the form of his

faith in a pure and spiritual love which could transcend the vagaries

of fate, even if his version of such love often existed outside the

realms of strict propriety.

He was

a popular artist of his time, speaking to audiences in a language they

could understand, even as he extended the expressive and thematic range

of that language. Of the seven films he completed only three were

released to the public in versions close to what he intended, and all

three made money — quite a lot of money. Von Stroheim knew his public

and its taste, and we err when we accept too quickly the judgment of

the studio executives who decided that this public would not have

accepted his four mutilated films in the longer versions he originally

prepared. We will never know for sure, of course, but it's an insult to

a popular artist of Von Stroheim's stature and achievement not to give

him the benefit of the doubt on this score and to accept uncritically

the verdict of the creative mediocrities who vandalized his films.

The

tale Von Stroheim concocted for what would have been his fourth film, Merry-Go-Round, is perhaps his most romantic — inspired as it was by

his nostalgia for the old Vienna he grew up in, the one that vanished

forever in the catastrophe of WWI. Von Stroheim's participation in this

old Vienna was not what he claimed it to have been — it was part of

his dream world from the start — but it was at the center of his

imaginative life and he seems to have felt its loss just as keenly as

(perhaps more keenly than) the loss of something real.

In Merry-Go-Round, Agnes becomes a symbol of the innocence and allure of

the dream of old Vienna — one which redeems the deceitful and

hypocritical Count Hohenegg, and by extension the whole corrupt

superstructure of the Hapsburg fantasy. That fantasy was worthwhile,

Von Stroheim seems to say, if it could make a place for dreamy,

waltz-inflected nights at the Prater, and for Agnes, the sweet

incarnation of those lyrical interludes.

When

we think of dreamlike films, or dream sequences within films, we might

be tempted to think of the expressionistic style filmmakers often use

to signal a dream state — but of course real dreams do not present

themselves in that way. We might, in a dream, find ourselves at home

and discover a previously unnoticed door opening onto a previously

unsuspected wing of the house — but that wing is not appointed like

the cabinet of Dr. Caligari . . . it is as convincingly real a place,

in the dream, as the actual house we know.

Von

Stroheim appropriated this aspect of actual dreams to give his

cinematic universe the power of the dream spaces we concoct, with a

similar attention to detail, in our sleep. This was Von Stroheim's way

of seducing us into his dreams, making us take them seriously. It was a

storyteller's strategy — not, as has often been suggested, some kind

of neurotic obsession with “realism”, much less an egotistical

extravagance. While Von Stroheim was obsessing over his “extravagant”

sets he himself lived in an exceedingly modest home in Hollywood, and

led a mostly mundane and largely domestic private life.

Von

Stroheim was the first great director to realize consciously that

movies alone could use this illusion of a coherent and convincing dream

universe to give power and depth and weight and resonance to an

ordinary tale, to overwhelm us with the subliminal power of an actual

dream.

Von

Stroheim was fired from Merry-Go-Round somewhere between a quarter

and a third into the shooting. The story was rewritten and the shooting

completed by Rupert Julian, a studio hack appointed by the dazzlingly

mediocre producer Irving Thalberg. Enough remains of Von Stroheim's

vision to show us what the film might have been — and there is more

than enough of Julian's work on display to make the genius of Von

Stroheim's method stand out in stark contrast.

Julian's

mise-en-scène is theatrical and uninventive, without a trace of plastic

imagination. He does not place us inside a dream universe but at the

edge of a stage. We don't have the sense of being someplace but of looking at something. Julian also encourages his actors to act — in an

exaggerated theatrical style that several of them had no training or

capacity for, and that violates in all cases the more naturalistic and

engaging style Von Stroheim knew how to elicit even from novices.

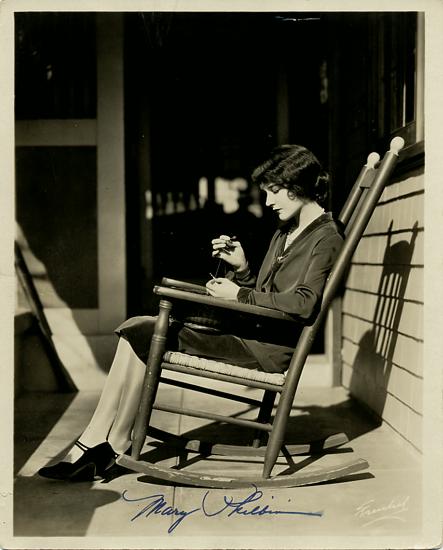

Despite

all that, the performances of Norman Kerry and Mary Philbin are

revelations. Kerry was playing his first important role here, and

Philbin her first role of any kind (apart from a walk-on in Foolish

Wives.) Kerry was a small-time actor whom Von Stroheim here elevated

to star status — and we can see in his performance what Von Stroheim

saw in him. He's sort of like a laid-back, less boyish John Gilbert,

with tremendous masculine authority, which seems utterly natural and

utterly appealing in those scenes directed or influenced by Von

Stroheim but which vanishes entirely in those scenes in which he is

called upon to emote in a more conventional (though already

anachronistic) style.

Philbin

was an actual discovery of Von Stroheim's — he'd named her as the

winner of a publicity-stunt beauty contest he judged in Chicago. She

has real charm and power in Merry-Go-Round, and also a totally

convincing naturalness — except when Julian persuades her to try for

the high style, at which point she seems merely competent. Her

generally undistinguished performance in The Phantom Of the Opera

must be attributed directly to Julian's cluelessness and bad taste as a

director of film actors, because she was an artist of genuine talent

and potential. (The fact that she became one of Universal's biggest

stars in the Twenties is yet more evidence of Von Stroheim's insight

into the popular taste of his time.)

Much

of Von Stroheim's dark vision of human behavior was removed from the

reworked version of the tale given to Julian to execute, which makes

the romantic idealism that triumphs in the end seem a bit saccharine.

Dimwits like Thalberg didn't understand how dark elements could set off

and energize the positive and redemptive themes always present in Von

Stroheim's work.

Universal

called its prestige releases Super-Jewels. The existing version of Merry-Go-Round is a Super-Rhinestone — but in it we can see

reflected a great masterpiece, the film Von Stroheim might have made

without the intervention of Irving Thalberg and his all-too-perfect

alter ego Rupert Julian.

DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER

This

is one of the nuttiest of the Connery Bond films and one of the most

enjoyable. Its narrative is borderline incoherent but that hardly seems

to matter to the filmmakers, who are simply using the plot as an excuse

for the sort of dumb/surreal gags that the series is famous for.

Watching this film you realize that Austin Powers is hardly a parody

at all — just a slight exaggeration of the tongue-in-cheek lunacy of

the early Bond films. This one seems to have been made by people on

some kind of drug that doesn't exist anymore — one part Merry

Pranksters LSD and two parts Rat Pack bourbon. The film is notable

visually for Jill St. John — unspeakably luscious here, performing

increasingly heroic deeds in increasingly fewer clothes . . .

. .

. and for images of Las Vegas in 1971 — from the shocking emptiness of

The Strip (Caesars was the only mega-resort in

existence at the time) to the wondrous dazzling neon of downtown, on

the western end of Fremont Street, before it was turned into a

pedestrian mall.

What's

more, Jay Sarno, creator of Caesars and Circus-Circus, and one of the

true visionaries of modern Las Vegas, plays a bit part as a carnival

barker at Circus-Circus:

You

can see Circus-Circus in this film exactly as it was when Hunter

Thompson first visited it in the early 70s and immortalized its

inspired, deranged essence. “The Circus-Circus,” he said, “is what the

whole hep world would be doing on Saturday night if the Nazis had won

the war.”

VISIONS

Here’s a link (via the ever illuminating Little Hokum Rag) to the amazing paintings of Shiori

Matsumoto. Just go to her site, click on Gallery and take a tour

through a previously uncharted precinct of Dreamland — east of

Tenniel’s Wonderland, west of the Henri Rousseau Rainforest, just down

the street from Chris Van Allsburg’s grandmother’s house. (Certain

traveling players pass between this region’s playhouses

and those on Amy Crehore’s Naughty Wondershow Theatrical Circuit,

exercising the craft and mystery of an art long thought lost.)

[Images © Shiori Matsumoto]

OH, MEXICO

My sister Libba, my dad and my sister Roe in Mexico.

Don't you wish you were there, too?

A ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

People who find an image like this excessively sentimental have simply

lost touch with reality — have learned to reject reflexively any work

which appeals too directly to the heart.

The image is contrived, certainly, in posing its subject between the

doll of childhood and the glamorized icon of womanhood, but there is

nothing contrived about the artist's subversive intention here.

The painting was made for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post,

which trafficked (at least in its advertising) in glamorous images of

women, like the one that is here filling a beautiful child's head with

doubt about her own attractiveness.

Rockwell's “Americana”, often seen as a sugar-coated lie, had its sharp

side. If this image doesn't make you just a little bit angry, and

deeply suspicious of a culture that seduces young women into such

self-doubt, then I think you just aren't seeing what's plainly there in front of you.

TASHLIN'S APOCALYPSE

Frank Tashlin's comic critique of American culture was

so anarchic, so all-inclusive — encompassing even the cinema itself,

the medium he worked in — that it's hard to identify a point of view,

a philosophy, behind it. He just seemed to celebrate the idea of

transgressive thought.

Still, critics have often intuited a dark side in

Tashlin's work, which suggests that it might not have been as

innocently and cheerfully irresponsible as it seems. Peter Bogdanovich

wrote, “As comic as Tashlin's movies are, they also reflect a deep

unhappiness with the condition of the world.”

But what might have been the source of this

unhappiness, the perspective on the world which determined it?

An interesting clue can be found in a short, 18-minute

stop-motion animation film he made in 1947 called The Way Of Peace.

My friend Paul Zahl, a distinguished Anglican theologian, recently

tracked down a copy of this obscure film — which is surprising, even

startling.

Tashlin started out in the world of animated cartoons,

and a few years before beginning his career as a live-action feature director

he made The Way Of Peace — which was, as far as I can

tell, his only foray into stop-motion puppet animation. The

stop-motion work was done by Wah Ming Chang, who later did the

stop-motion effects for The Seven Faces Of Dr. Lao and The Time

Machine. The film was narrated by the actor Lew Ayres.

But

here's the startling part — the film was made for

the Evangelical Lutheran Church Of America, and it's an unabashedly

religious, Christian work. Most of it is concerned with the

destruction of the world by nuclear holocaust, presented as an

inevitable consequence of abandoning Christ's “way of peace”. (A

Lutheran pastor provided the “story conception” for The Way Of Peace, but

Tashlin wrote the script and clearly devoted a lot of care to the

inventive, often beautiful, often terrifying images of the film.)

One might think, given the puppet-cartoon medium it's

made in, that it was a film addressed to children — but the

apocalyptic destruction it portrays is very dark and disturbing. At

any rate, it's probably not something you'd want to show to very small

children — the natural audience for animation of this sort.

It turns out, however, that Tashlin wrote a number of

picture books for children which are far more explicit in expressing

his fears for human civilization than his Hollywood movies ever tried

to be. Tashlin's fears were founded on a dread of nuclear war but also

on the spiritual decline of civilization through materialism —

something he satirized mercilessly in his films.

Tashlin being Tashlin, of course, his critique of the

modern world did not preclude a critique of the church — he was no

apologist for organized religion. A church is shown being obliterated

in the finale of The Way Of Peace, and one of his children's books, The World That Isn't, criticizes churches for their complacency.

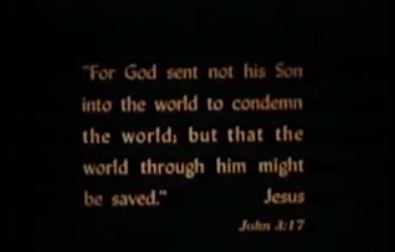

I think all of Tashlin's work needs to be re-examined

in light of The Way Of Peace and his children's books. The Way Of Peace even offers a clue as to Tashlin's oddly affectionate, even

celebratory style of satire. The short ends with a quote from John's Gospel:

Paul

Zahl points out that there is Tashlinesque irony in the quote, since

we've just witnessed the destruction of the entire planet — but the

theology is sound enough from a Lutheran perspective, and perhaps from

Tashlin's. God hasn't destroyed the world for rejecting Jesus, the

world has destroyed itself by rejecting Jesus's “way of peace”. There

is no judgment involved, per se — just a kind of spiritual physics that reflects a very grim view of human nature.

Tashlin's mainstream Hollywood work never passes judgment on anyone or anything (The Girl Can't Help

It!) . . . but was it meant to save sinners, instead of just tweak them

for

their follies?

Tashlin, along with his disciple Jerry Lewis, was

probably the most eccentric director of comedy in 50s and 60s

Hollywood. Was he perhaps even more eccentric than we've imagined —

and more profoundly serious in his deconstruction of American

civilization? In The Way Of Peace he

portrays a puppet world on the brink of annihilation. Was that

perhaps what he was trying to do, between the lines, in his live-action features as well?

Another of his children's books offers an intriguing image which might be the best clue to the real Tashlin and his methods — The Possum That Didn't.

In it, a happy possum hanging upside down has his smile mistaken for a

frown. A bunch of do-gooders take him to the city, where he's

unhappy, but his upside-down frown there is mistaken for a smile.

To

me this sounds an awful lot like a warning directed at anyone inclined

to take Tashlin's topsy-turvy comic vision at face value. At the

very least it should make us question whether his smile is ever quite

what it seems.

[The Way Of Peace can now be seen, in a somewhat

fuzzy online version, at the web site of the Evangelical Lutheran

Church Of America, which holds a copy of the film. It's really a

remarkable and provocative piece of work. Thanks are owed to that

organization for putting it up, and to Paul Zahl for tracking it down

there.]

JOHN WILLIAM WATERHOUSE: A VICTORIAN ARTIST YOU SHOULD KNOW

Actually, if there’s a Victorian artist you do know, it’s probably John William Waterhouse. Prints of his paintings are quite popular, and it’s not hard to see why. He

combines the dreamy Romanticism of the Pre-Raphaelites with a bold

modeling of forms and an optical integrity that suggests a nearly

photographic realism, however free his treatment of the paint surface.

His process seems to have involved a strict linear draftsmanship to

which he applied sketchy strokes of paint as he worked out the color

scheme of the final image.

He then blended the colors into more modeled forms for the finished

work, but retained something of the freshness of his sketches.

Impressionism was a stage in his process, never an end in itself.

His primary goal was narrative suggestiveness and the creation of a

world, theatrical as it might be, which convinced the eye with the

illusion of space and stereometric forms. Note the sharp relief

of the figures in the painting at the head of this post and the

sketchier view of the coast behind them. The contrast of

treatment itself creates a sense of deeper space.

Andrew Lloyd Webber owns the painting below. I’d have bought it, too, if I had his resources — it’s just miraculous:

WHAT IS REFRIGERATOR ELVIS WEARING TODAY?

Oh, look — it's the famous gold suit by Nudie Of Hollywood, commisioned for Elvis by Colonel Parker. Elvis thought it was

a bit too much for stage appearances but often wore just the coat with black pants. Cat clothes!

OUT OF THE PAST

As opposed to murder mysteries (for example), which are basically

intellectual puzzles organized around a frisson or two, great suspense

thrillers — which include many different kinds of movies, from

Hitchcock to classic film noir — are rarely about their nominal subjects. Their plots are

constructions designed to investigate and expose various modes of

existential dread which would be too uncomfortable to face directly but

which are thrilling to experience when disguised as mere

amusement. The process is very similar to what happens in dreams,

in which we find visual and plastic equivalents to inner tensions which

the conscious mind prefers to avoid confronting head-on.

There’s a smooth continuum between the suspense thriller and the horror

film, the latter category being reached when the subject of death,

bodily decay and destruction is foregrounded and taken right up to the

edge of what the mind is willing to process within a work of

entertainment. (Convention and the age of audience members play

a large part in determining where that edge begins.)

The film noir tradition, which began during and flourished just after WWII, expanded the limits of dread which American movie audiences would accept — and obviously the

horrors of the global conflict played a determining role in this development. Film noir

reflected a new cynicism about politics, since politicians had failed

to prevent the war, about civilization, which had been exposed as a

veneer beneath which savagery lurked, and about human nature, because

ordinary people did unspeakable things to each other in the course of

the war.

But most of all, film noir, at its heart, reflected a new insecurity about manhood.

Charles Lindbergh, before the war, wrote of his fear that a truly

global conflict would sap the virility of the civilized world and

create a vacuum in which demons would breed. He wasn’t just

talking about the young men who would be killed but the young men

whose experience of war would exhaust their spirits — leave them unfit

for the business of domestic life, the hard work of peacetime

civilization.

I think this was a profound insight, and helps explain the crisis of

manhood which afflicted 50s America and which came to fruition in the

epidemic of divorce in the 60s, along with a general retreat from male

responsibility to the institutions of marriage and the family.

The greatest generation had given all it had — its reserves of service

and sacrifice were used up.

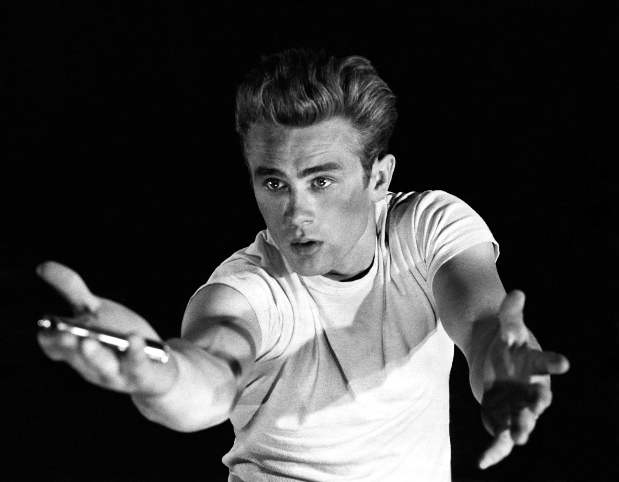

This also helps explain the disaffection of youth in the 50s and

60s, the nihilism of the Beats, the rebellion of rock and roll, the search

for newer and more authentic male role models like James Dean and Elvis

Presley — all of which culminated in a radical rejection of older male

paradigms in the 60s, in the de-sexing of the male which began with the

adolescent image of the early Beatles and ended with the long-haired

male flower child.

There was much that was positive in this cultural shift, but its root

causes and possible consequences remained largely unexamined, along

with its dark side — which was an increasing fear and hatred of women,

who could not help but represent an accusation aimed at male

uncertainty and insecurity.

It’s curious, I think, in an age which celebrates feminism and the new

sensitivity of males, that our popular culture degrades and commodifies

women to a far greater degree than earlier, frankly patriarchal

societies. Camille Paglia provided the key to this paradox when

she observed that the status of women today is determined not by a

patriarchy which has gown too powerful but by a patriarchy which has

collapsed, grown unsure of itself.

Film noir is the place to begin a study of this whole, strange phenomenon. Look at a film like Out Of the Past, one of the classics of the tradition. On one level it’s a crime

thriller, an exposé of social corruption, an exercise in cynicism about

everything. But this level is superficial. At the heart

of its tension is a vision of things gone horribly wrong between the

sexes — the dream of a lost romantic paradise, the fear that real

partnership and co-operation were no longer options, the nightmare of a

fraudulent and impossible romantic redemption.

At the center of most great filmsin the noir tradition is the femme fatale

— a tough, independent, alluring figure who’s dangerous precisely

because she exploits the impotence of her male counterpoint. The

collapsed male projects, as he always must, his own inner chaos onto

the female who exposes his weakness, his existential nullity in a

culture that no longer knows what it means to be a man.

Check out the image below, where Robert Mitchum holds on to his

inadequate cigarette-phallus and Jane Greer seems to ask, “Is that it

— is that all you’ve got?”:

Cigarettes are almost always more than cigarettes in film noir.

The tough guys always reach for them when they’re trying to be hard and

cool — and when a woman smokes a cigarette, she’s usually getting

ready to un-man somebody.

The femme fatale of the film noir tradition is the mother of our modern world. It has no father.

IT'S COMING

I'm excited — aren't you?

MONUMENTS

Last summer I made an epic 7,000-mile road trip with my sister Lee and her two kids, Nora (who was 9) and Harry (who was

12 when we started the trip and 13 by the time it was over.)

We

drove from Las Vegas to the coast of North Carolina then back by way of Upstate New York.

In the course of the journey we made pilgrimages to sites of deep Americana, the first of

which was Monument Valley, which straddles the Utah-Arizona border.

This of course is where John Ford filmed many of his Westerns. The inn

his company stayed at when on location there is still in business, with

a museum and part of the outbuilding that doubled for Colonel Nathan

Brittles' quarters in She Wore A Yellow Ribbon:

[The boulder on top of the roof is a prop.]

You

can see immediately why Ford loved this location. Although its mesas

and rock formations are indeed monumental, they have an almost human

scale — unlike the Grand Canyon, for example. (If the Grand

Canyon can be ranked among God's masterpieces, Monument Valley was a pièce d'occasion.) And the formations in Monument Valley are scattered

about in a pattern that yields new vistas, a new sense of space, every

few hundred yards. It might have been built as an epic movie set.

It's

weird to visit a place you feel you know well just from movies, and

moving to visit a place that a great artist has appropriated as part of

his myth about America, a myth that has helped shape what America is,

or at least how it sees itself. The scenic route through the valley is

still just a dirt road, rough even on my high-slung 4-WD vehicle. The

valley is heavily visited, but you still get a sense of being in a

wilderness, or a dream of wilderness . . . the other tourists are like

fellow audience members in a dark movie theater, there but not there.