Nicholas Ray's On Dangerous Ground is a problematic film noir on many grounds but in an odd way it helps define the genre. More precisely, it helps us realize that film noir

isn't really a genre at all but a way of identifying a particular

strain of post-WWII dread as it came to infect many different kinds of

film.

This strain was characterized by a sense that the world had gone

hopelessly wrong, that existing paradigms for male identity were

suddenly useless in terms of setting anything right, that women, faced

with the existential nullity of men, were sudddenly in a position to

destroy them at will.

It's this profound and comprehensive existential dread that distinguishes film noir

from the dark pulp fiction of the Thirties, which investigated the

corruption of American society through the eyes of cynical but

personally incorruptible men like Chandler's Phillip Marlowe, or the

crime thrillers which gave us glimpses of the underworld while still

positing forces which could combat and contain it.

These popular forms took us on a tour of the wild side, the dark side of American culture, but the film noir suggested that there was no other side.

On Dangerous Ground violates every standard rule of Hollywood storytelling, and eventually most rules of the noir

tradition. The dream logic that propels the narratives of all

great suspense thrillers is stretched beyond conventional bounds —

just as in dreams sometimes incidents occur which make us realize, even

in the middle of the dream, that we must be dreaming.

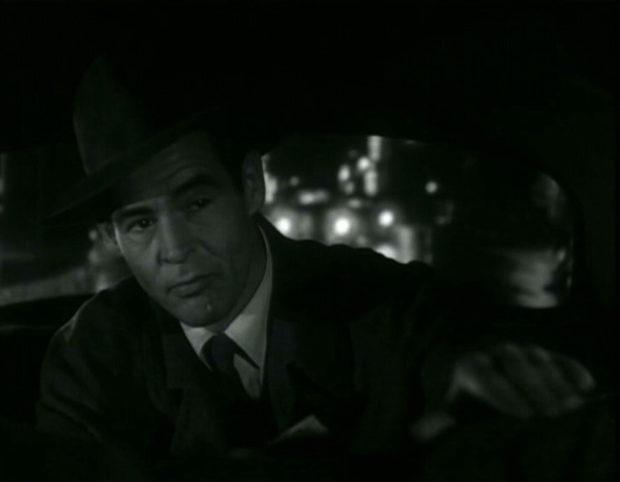

Robert Ryan plays a cop on the edge of a total breakdown, overcome by

the sheer meanness of streets which can't be policed effectively except

by adopting the rules of the bad guys. For his own good he's sent

out to a rural community to help with a murder investigation, but

there's nothing redemptive about the country he enters. Bleak,

snow-covered, peopled by vicious, suspicious, isolated farm-dwellers,

it's just as soul-killing as the city he's left. It reminds one

of the landscape of Bergman's Winter Light — a place where the soul shrivels and dies.

But then he meets a woman, played by Ida Lupino — not the traditional femme fatale who waits to ensnare and destroy lost men in many films noirs

. . . but a blind woman paradoxically attracted by his distant,

unengaged treatment of her. His failure to pity or patronize her

gives her a sense of power, encourages her to trust him,

irrationally. And that trust saves him, gives his existence some

meaning.

The film, made at RKO, was much meddled with by studio head Howard

Hughes, which may account in part for its disjointed tone. Ray

disowned the film in later years, saying that Ryan's redemption

involved a miracle and that he didn't believe in miracles.

But the film believes in this particular miracle, and that's all that

counts. And even the miracle fails to violate entirely the dark

vision of the film noir,

since it presents us with a love that's possible only because both

partners in it are disabled, outsiders, in touch finally with their own

despair because they're able to recognize it in each other.

You could call it a religious film — and you wouldn't be far wrong.