Someone once remarked that there's no such thing as a bad film noir. It's a strange propostion and the strangest thing about it is that it's pretty much true.

I've just watched over 30 films noirs

and none of them was anything less than a wondrously entertaining

B-picture. There are some clunkers that are labelled films noirs but really aren't — like Otto Preminger's Whirlpool,

for example, which is in fact a Hitchcockian suspense thriller made by

a man who had no clue as to how Hitchcock created suspense . . . but even among the faux noirs, films that are noirish only in visual style, for example, most have dialogue and images that are thrilling.

I'm not sure how to explain this consistency of quality except by suggesting that noir

represented such a release from the thematic and stylistic conventions

of the traditional studio product that filmmakers responded with an

outburst of pent-up creativity and daring. They must have known

that they were inventing a new kind of film, even if it didn't have a

name yet, and the fact that there were no set rules for this kind of

film made it hard for the studios to wrestle it into a set

formula. Films noirs

were relatively cheap to make, and people couldn't seem to get enough

of them, so the studios stepped back and let the experimentation

continue — for almost 20 years.

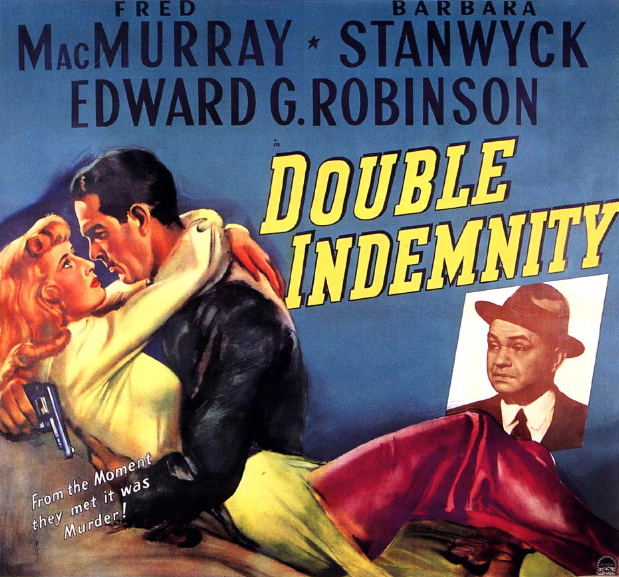

The first film that displayed the characteristic visual style of the noir was a fairly routine murder mystery called I Wake Up Screaming (above) from 1941. Double Indemnity, from 1944, gave us protagonists who were morally currupt to the core. Neither was, to my way of thinking, a genuine film noir, but Double Indemnity

was a radical indication that a change was on its way — that audiences

could accept a darker view of the world than the Hollywood studios had ever been

willing to embrace.

As early as 1945, in Edgar G. Ulmer's no-budget thriller Detour,

the combination of an exaggerated, expressionistic visual style and a

sense of the world as morally unhinged at its core produced a template

for the classic film noir, a vehicle for the subterranean mood of existential dread that gripped America in the wake of WWII.

None of the movies made about the war itself ever expressed as

eloquently its psychic cost to a generation of Americans as did the

movies we now call film noirs.

They crackle with the excitement of artists suddenly allowed to deal

with truths that couldn't be addressed in the official view of

things. Corporate entertainment tends to gravitate towards the

official view of things but there are times when the official view of

things diverges so radically from the actual mood of the audience that

accommmodations have to be made. Film noir was one of the most radical of those accommodations.