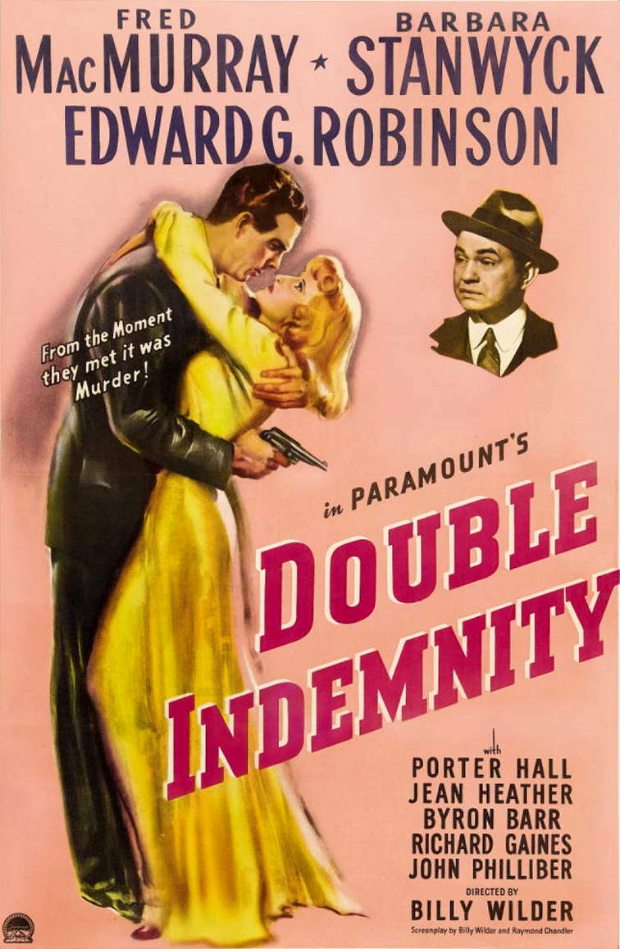

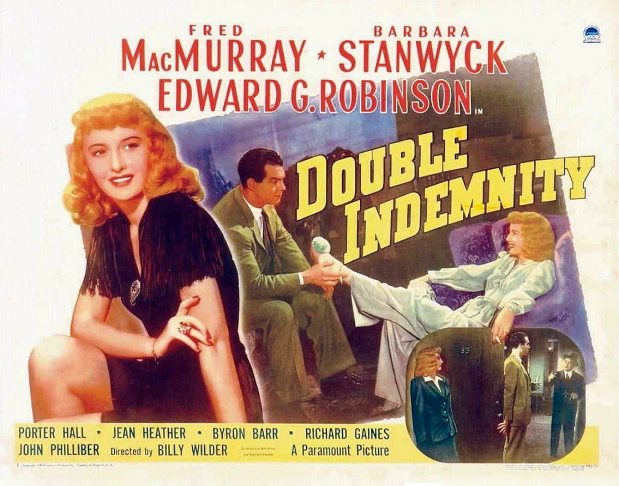

Double Indemnity is generally seen as one of the first (and one of the best) films noirs but I don’t think it fits comfortably into the category. It shares with the true film noir protagonists who are infected with a moral corruption that destroys them. Unlike a true film noir, however, the film doesn’t present this corruption as part of a universal human condition, or as the result of a breakdown of humane values in society as a whole. In the true film noir

the doomed hero is often sped along to destruction by honest mistakes or innocent choices, and just as often is given no course of positive action which would save him. When he makes bad choices they’re frequently motivated by a position of powerlessness in the social order, particularly economic hardship or unjust persecution by the law.

In Double Indemnity, Walter Neff and Phyllis Dietrichson live comfortable lives. Their passion and their greed are not presented as responses to any kind of social oppression, unless it’s the sheer boredom of middle-class life. They’re simply selfish, amoral people.

The film can be read as a critique of middle-class American life, seeing the corruption of the adulterous lovers as a product of the spiritual vacuity of their class, but to me the tone of the film is more peevish and bitchy than political. You get a sense that Chandler and Wilder, who did the adaptation of Cain’s book, hate their bourgeois characters because they’re stupid and tacky — that it’s snobbery that ignites the engine of the narrative. Certainly there’s no sympathy involved and no rage directed at the system which produces such people.

Made during WWII, the film taps into the creeping spiritual malaise and suspicion of civilization, as well as the sense of the existential impotence of men, that would inform the postwar film noir — and it portrays one of the most fatal femmes in the entire history of cinema. But I think these things are mostly the result of coincidence, an intuition about the temper of the times that allowed Chandler and Wilder to indulge what was primarily a personal prejudice against their social and intellectual inferiors. To them, I think, Walter Neff’s biggest crime wasn’t murder — it was his dumb salesman’s jokes and the self-satisfied way he delivered them. Phyllis Dietrichson‘s one unforgivable sin was the cheap blonde wig.

I’m talking here about the philosophical mood of the film, the attitude of the creators, but of course those things are transformed in the film itself, whose dark undertow of suspense and fatal miscalculation is so powerful that it transcends the bitchiness of Wilder and Chandler, evoking an anxiety far deeper than the snob’s fear of bad taste. Double Indemnity, finally, achieves the precise effect of a nightmare, while not venturing into the precise nightmare landscape of the true film noir.