“What we all dread most,” said G. K. Chesterton’s detective priest Father Brown, “is a maze with no centre.”

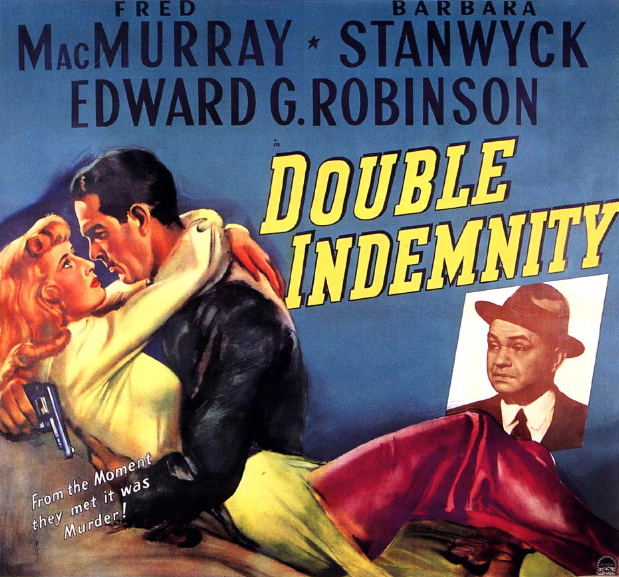

The mood of existential dread that gripped the American psyche in the wake

of WWII was largely unconscious, and so it expressed itself in

irrational ways — in the hysteria of the Communist witch hunts, for

example, and in the mythology of the film noir,

which characteristically sent an impotent man into the heart of a

nightmarish moral labyrinth from which there was no escape.

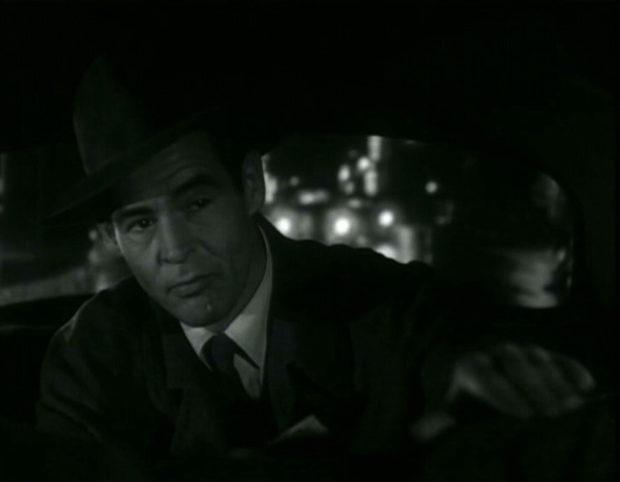

There was a variant on the classic noir paradigm which sent a cop or a government agent into that same dark underworld, but he was armed with the positive values of the official

culture and backed by its official institutions — he not only escaped from the labyrinth, he straightened it out, brought it into the light and broke its evil spell.

The first film of this kind, and a model for all the rest, was The House On 92nd Street

from 1945, an F. B. I. procedural about the uncovering of a Nazi spy

ring operating inside the U. S. during WWII. It had a

quasi-documentry approach and was obviously designed to reassure

Americans that their government had the issue of existential dread well

in hand. It’s a taut, entertaining thriller, with fascinating

location photography, but its celebration of the F. B. I.’s

omnipotence and infallibility couldn’t, even at the time, have been a

profound assurance to people who felt that something had gone terribly

awry with the world — something that the Allied victory in the war

hadn’t really set right.

This feeling was addressed but not answered in genuine film noir,

which is what gave the form its power — turned its image of the urban

labyrinth into an enduring variation on an ancient myth.

Interestingly, the terrifying image of the maze with no center, and no

exit once entered, can also be found I believe in the best films of

Frank Tashlin — all comedies.

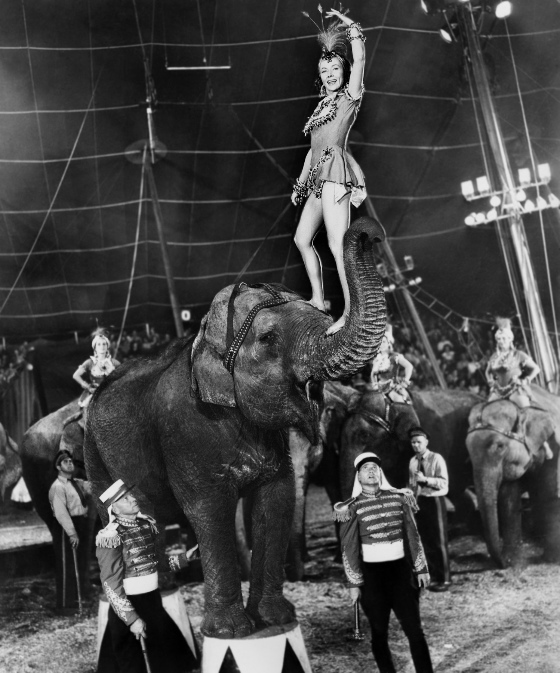

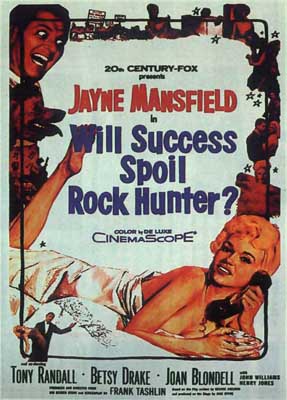

In The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?,

Tashlin offers a satire of post-war American culture which also has no

center and no exit point. These movies mock modern media from within the

modern medium of film, which is itself mocked, deconstructed, leaving us

with no reliable perspective from which to judge any of their judgments.

They savage the modern rat race but also savage anyone who tries to

escape it. In Tashlin’s vision, as in film noir, American culture is a maze which can’t be navigated, in which every passage circles back on itself.

In Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?,

for example, Tashlin attacks modern advertising and product placement

on television, then proceeds to plug his own earlier film The Girl Can’t Help It

within the new one. Tashlin’s films are funny but deeply

disturbing. Their vision of America is profound and just as noir as the dark streets of the great films noirs. The fact that Tashlin’s darkness is rendered in garish, overheated

Color by Deluxe is just one more of the radically disorienting ironies

of his method.

[For more on The Girl Can’t Help It, go here. The image of the labyrinth in film noir is discussed helpfully in Nicholas Christopher’s book Somewhere In the Night.]