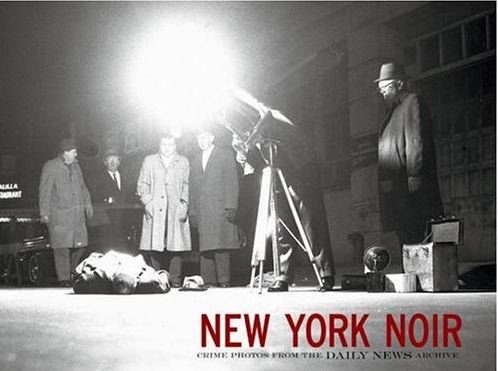

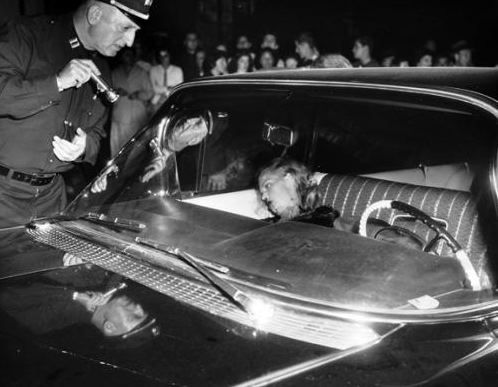

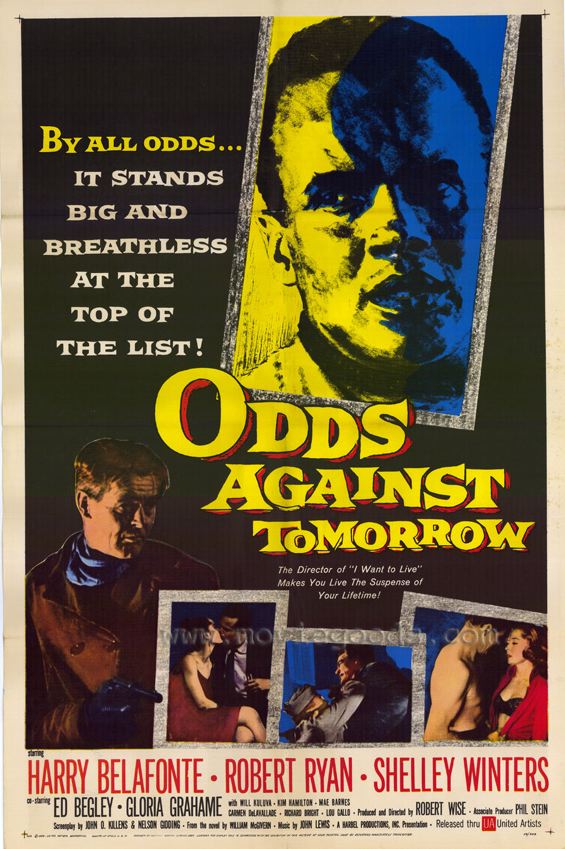

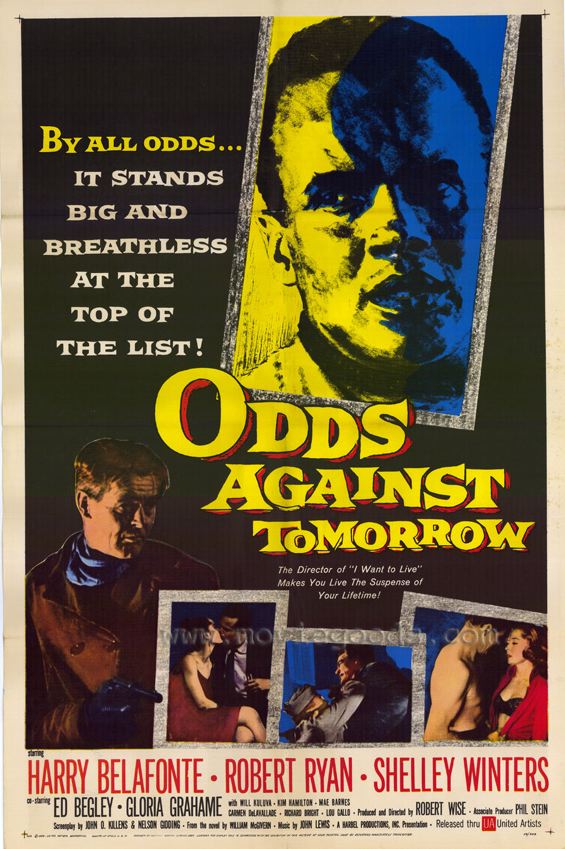

Touch Of Evil is sometimes cited as the last classic film noir but I'd nominate in its place Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow, which came out a year later. Odds Against Tomorrow is certainly a true noir, as well as one of the greatest films in the tradition, and its themes recapitulate the core themes of noir with elegant clarity, while at the same time looking forward to the post-noir future.

Odds Against Tomorrow is steeped in the mood of existential dread that characterizes the classic film noir

— and more specifically the sense of male impotence in the face of a

world gone horribly wrong. It makes sense to see the root of this

dread in the global catastrophe that was WWII and in the spectre of

global annihilation summoned up by the atomic bomb — and Odds Against Tomorrow deals directly with both these themes.

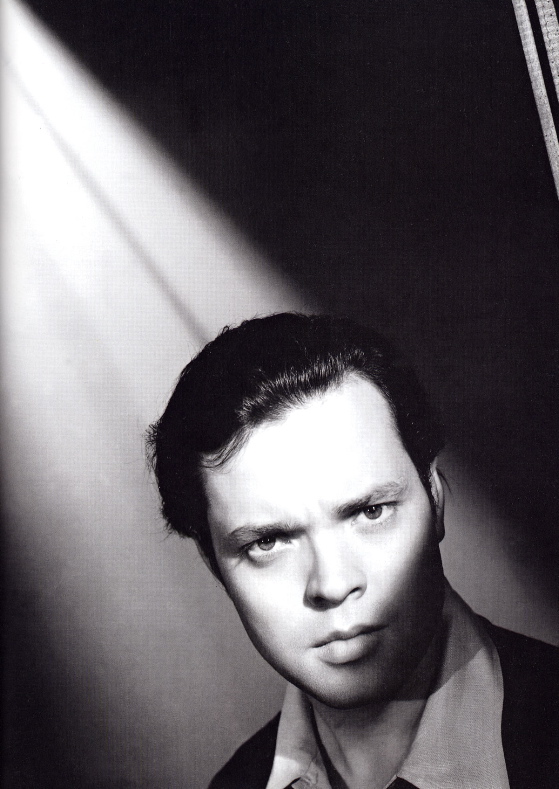

Robert Ryan's character is an aging WWII vet whose capacity for

violence is no longer needed — is a bewildering liability in the

post-war world. He has a sense that his best days are past, that

he has no place in society, and this fear un-mans him, all but destroys

his relationship with a woman who truly loves him but whose ability to

earn more money than he can fills him with shame and self-loathing.

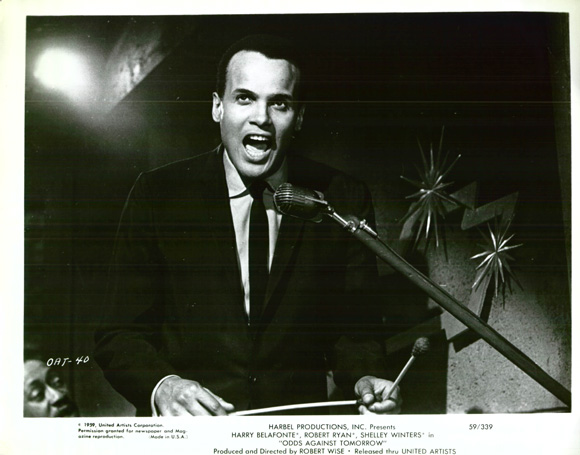

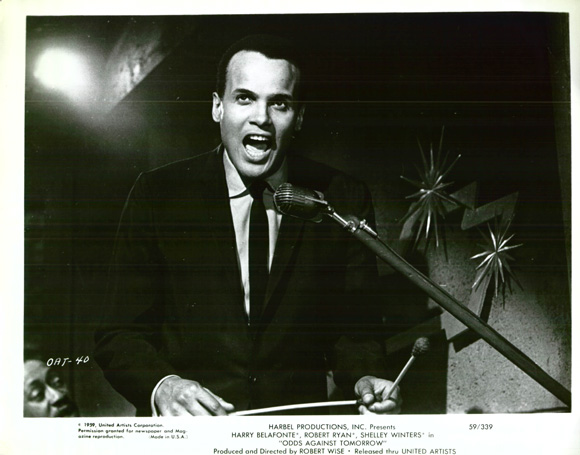

Harry Belafonte's character is also a war vet, but as a black man his

sense of impotence in a white world is even more intense. The

Ryan character suffers from deep psychological wounds — the Belafonte

character has a handicap in a racist society that nothing could possibly cure . . . the color of

his skin. He's a jazz singer but addicted to gambling, to finding

the one big score that will enable him to tell the white

nightclub owners he works for to kiss his ass. His gambling, however, has wrecked

his relationship with his wife and made him incapable of being a true

father to his daughter. Assaulted from without and within, his

sense of himself as a man has imploded.

These two characters are brought together for a crime caper by a crooked ex-cop, who incarnates the assumption in films noirs that corruption is universal.

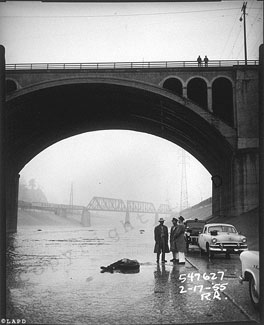

The shadow of the atomic bomb is omnipresent in the film — to a greater degree than it is even in Kiss Me Deadly, another classic noir which makes a clear connection between its bleak mood and atomic-age anxiety. In Odds Against Tomorrow characters

refer to the bomb on several occasions, and the explosive climax of the

film references it visually and metaphorically.

When the subtext of a tradition like film noir

gets as close to the surface as it is in this film you can be pretty

sure that the tradition is just about played out. Film noir didn't disappear after Odds Against Tomorrow, but it became something else — neo-noir, which is always, at least in part, a commentary on the old form in its less self-conscious incarnation. But by centering

the psychological dread of a character like Belafonte's in a particular social

problem like racism, the ground is prepared for the politically

conscious films of the Sixties and onward. True noir, while

always attuned to social ills, and always political in that sense,

trafficked in a more existential brand of hopelessness. Odds Against Tomorrow, which was financed by Belafonte himself, looks forward to a time of action.

Belafonte gives a terrific performance in the film — he's appealing

and incredibly cool but hard-edged. His rage and resentment don't

seem ideological or didactic but deeply personal. Ryan's

performance as the washed-up thug, whose racism is just another mask

for his impotence, is one of the best of his career, with a creepiness

that's also touching, and all the more creepy for that.

The film is beautifully shot, mostly on location in Manhattan and in

Upstate New York — and yet a few annoying, pretentious zooms remind us

that the end of the classic noir

style is at hand. Apart from that it's a brilliant film on every

level — maybe Wise's best — and it certainly belongs in the classic film noir canon. In fact, I think you could say that, like Ryan's aging boxer in Wise's The Set-Up, the film noir tradition goes out here with one last improbable, bittersweet triumph.