It’s a commonplace of writing about film noir to see its dark, moody lighting as derived more or less directly from the German expressionist cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, best

exemplified in work done at the UFA studio in Berlin. The proposition is logical enough — the “UFA style” had become a kind of shorthand in Hollywood for highly exaggerated, expressionistic lighting, and many of the cinematographers and directors associated

with film noir had European backgrounds, with experience working at UFA itself or in traditions influenced by it.

The proposition gets a little shaky, however, when you examine the visual style of film noir

with a careful attention to detail. Its resemblance to the look of UFA-style expressionism is mostly superficial. The UFA style had a Romantic quality, evoking candlelight and gaslight rather more than popping flashbulbs, stabbing headlights and glaring neon — which characterized the noir style. The UFA influence is very clear in the Hollywood horror film cycle of the 30s, with its atmospheric, Gothic sets and lighting — but it’s less clear in the jagged edges of light, the jarring collisions of black and white in film noir.

As I’ve written elsewhere: “Lotte Eisner sees Murnau’s visual strategy [in Faust] as one which opposes darkness against light, but this is not quite right, for Faust is not a film of stark contrasts, but of chiaroscuro, of subtle gradations and complications. Light itself is in some ways the protagonist of the film, its mysterious workings and shadings offering a mystical perspective, making the characters and settings emblematic but also providing consolation and inspiration — the sense of a world animated by Spirit.” This was true of many films in the German expressionist tradition — and was decidedly not the visual strategy of film noir.

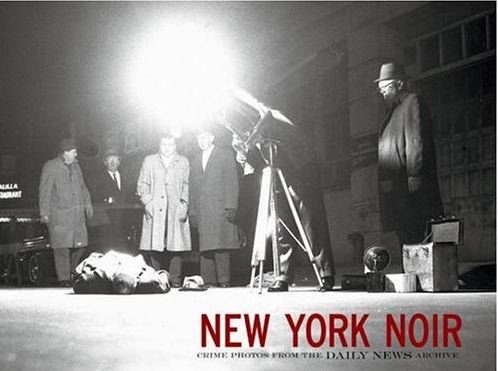

There’s another, home-grown visual tradition that I think had a much clearer influence on the look of noir — the American tabloid crime photography of the 1930s and 1940s. A book called New York Noir makes a very convincing case for this influence. It collects images from the pages of the New York Daily News and most of these images echo the look of film noir far more closely than the great films made at UFA.

The visual style in question begins with the adoption of the Speed Graphic camera by the Daily News photographers in the 30s. Its faster film stocks, along with developments in synchronized flash technology, allowed these photographers to penetrate the night for the first time. The flash itself created bold contrasts of light and dark and helped construct the public image of the night-time city, especially its seamy underside — an image that is faithfully explored in classic films noirs.

Weegee was the most famous of the Daily News photographers — his book Naked City brought the public a conscious awareness of the tabloid style as a distinct phenomenon,

recognized directly by filmmakers Hellinger and Dassin when they bought the book’s title

for their New York police procedural movie of the same name. But Weegee was just one of many great tabloid photographers who pioneered this style, who lodged it in the public imagination.

The great filmmakers who worked at UFA before WWII, including many who

eventually made their way to Hollywood, certainly developed and codified expressionistic lighting in movies — but I think the many, mostly anonymous photographers who snapped pictures of crime scenes for the American tabloids had a much greater and more direct influence of the look of the film noir.

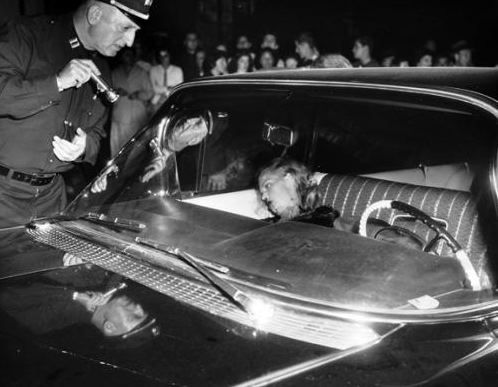

The frame below, from Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, seems to be trying to invoke precisely the look of a tabloid crime scene photograph: