There's

now a button in the column to the left (Film Reviews A-Z) which will

take you to a list of all the movies reviewed on the site and allow you

to link to them directly.

Monthly Archives: July 2007

FILMS REVIEWED

Amarilly Of Clothesline Alley

Apocalypto

Baby Face

The Bad and the Beautiful

The Bellboy

The Big Combo

The Big Trail

The Birds

Blind Husbands

Born Reckless

Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia

Casablanca

Cherry 2000

Cheyenne Autumn

Chimes At Midnight (Falstaff)

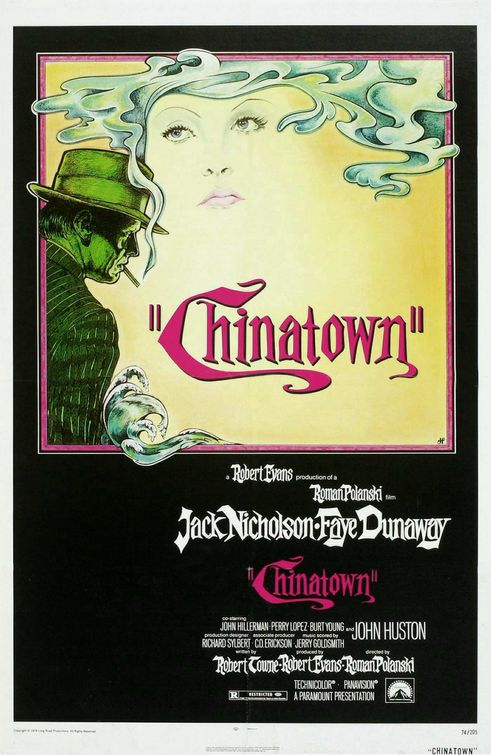

Chinatown

Citizen Kane

City Girl

The Civil War

The Clock

The Conformist

Contraband

Crime Wave

Daisy Kenyon

The Dark Corner

Diamonds Are Forever

Double Indemnity

Dracula (1931)

The Dreamers

El Cid

Electric Edwardians (DVD Collection)

Eternal Sunshine Of the Spotless Mind

Eyes Wide Shut

Falstaff (Chimes At Midnight)

Flesh and the Devil

Force Of Evil

Four Sons

G. I. Blues

The Garden Of Eden

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir

The Girl Can’t Help It

The Glass Bottom Boat

The Great K & A Train Robbery

Hangman’s House

He Who Gets Slapped

Headin’ Home

How Green Was My Valley

The Hunchback Of Notre Dame (1923)

I Confess/The Wrong Man

Intolerance

The Iron Horse

It’s All True

Just Pals

King Kong (2005)

The Ladies Man (1961)

Laugh, Clown, Laugh

Laura

Lawrence Of Arabia

Leap Year

Leave Her To Heaven

The Lord Of the Rings

Loving You

The Marriage Circle

The Married Virgin

Merry-Go-Round

Miss Lulu Bette/Why Change Your Wife?

Mr. Arkadin (Confidential Report)

My Best Girl

1900

Nosferatu (1922)

Odds Against Tomorrow

On Dangerous Ground

Out Of the Past

The Oyster Princess

Pandora’s Box

The Penalty

Peter Pan (1924)

Pilgrimage

Pitfall

Sadie Thompson (1928)

Saved

Scarlet Street

Seas Beneath

The Set-Up

Shadow Of A Doubt

The Shop Around the Corner

Show People

Spider-Man 2

Summer Magic

Sumurun

The Sundowners

They Live By Night

3 Bad Men

The Three Burials Of Melquiades Estrada

Titanic

Tobacco Road

Trapped

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1927)

Up the River

Vertigo

Vicky Cristina Barcelona

War Of the Worlds (2005)

The Way Of Peace (Frank Tashlin Short)

What Time Is It There?

Why Change Your Wife?/Miss Lulu Bette

Why Worry?

The World Moves On

The Wrong Man/I Confess

THE FILM NOIR CANON

People who love film noir also love to argue about what films belong in the category and what films don't. They compile lists of films noirs and break them down into subcategories. The general drift of this activity is to call almost any film noir

as long as it was made in Hollywood in the 1940s or 1950s, in black

and white, and features moody lighting, cynical attitudes and

some content related to crime.

This inclusiveness is abetted by studio home video departments, which will designate any film with the above attributes a film noir because the label is sexy and apparently helps sell DVDs.

In the process, the term gets so vague as to be useless. I would

argue that there is a core set of films that are truly and uniquely noir,

reflecting a particular time in America, with a particular mind-set, a

mood of existential dread that seemed to invade the American psyche

after the end of WWII, at the beginning of the atomic age.

This sense of dread was in the air before then, of course, as the world

hurtled towards war. It can be felt very clearly in some dark

films made during the war — in Hitchcock's Shadow Of A Doubt, in Wilder's Double Indemnity, in Huston's The Maltese Falcon. The first two of those films, along with Leave Her To Heaven, fall into a distinct category of their own — the domestic noir.

The Maltese Falcon seems on its surface to belong to another distinct category, the hardboiled detective thriller, which had noirish

elements but whose essentially noble protagonist rescued it from

existential dread. Yet Bogart's Sam Spade seems to be losing

faith in the nobility of his code, to see it as meaningless, and I

think that fact alone allows one to call The Maltese Falcon a true film noir. Just compare Bogart's Spade to his Phillip Marlowe in The Big Sleep, which plays like a hardboiled romantic comedy by comparison with Huston's film.

The point about The Maltese Falcon can be argued, of course, and I place it among the true films noirs with that reservation in mind. Here are some of the other films I think of as truly noir, without such reservations:

Out Of the Past

The Killers

His Kind Of Woman

The Dark Corner

The Set-Up

Gun Crazy

Fallen Angel

Angel Face

Touch Of Evil

Detour

The Wrong Man

Criss Cross

The Killing

In A Lonely Place

On Dangerous Ground

Crossfire

Where the Sidewalk Ends

Brute Force

The Sweet Smell Of Success

Night and the City

Thieves Highway

The Lady From Shanghai

14 Hours

The Long Night

Nightmare Alley

Odds Against Tomorrow

Act Of Violence

Crime Wave

They Live By Night

Decoy

The Big Steal

Side Street

Where Danger Lives

Tension

Kansas City Confidential

The Big Combo

Gilda

Note that not all of these films end badly for the protagonist, and not all of them feature femmes fatales — several actually have femmes

that rescue the protagonist, and in one of them the protagonist is

rescued, just as improbably, by Jesus. But in all of them the

protagonist needs rescuing, in all of them he's lost in a nightmare world that's

existentially different from the world that existed before WWII and he can't, by his own efforts, get out of it.

Even a film like His Kind Of Woman, which goofs comically on this world, is also recognizing it.

In future posts I'll list some of the films commonly called noir

which I don't think really are, because, though they may reflect to one

degree or another the same existential dread as the true noir,

they don't acknowledge it as a profound and inescapable condition.

It's almost a spiritual distinction, and therefore hard to

define precisely, but I think it's one worth making.

A BOUGUEREAU FOR TODAY

Bouguereau’s figures are so solid that when he sets them floating in the air the effect is unsettling, uncanny, but in a pleasant way, as flying in dreams is pleasant.

CHINATOWN

Chinatown is one of the few neo-noirs that really lives up to the designation. Its view of the world is truly bleak — a moral maze from which there is no escape. As with many films noirs there’s an indictment of the political system but also a sense that corruption

is universal, not limited to any one class. It’s an existential corruption.

The big difference between Chinatown and the classic post-WWII noirs is one of gender perspective. The post-war noirs were centrally concerned with male anxieties, with the way the world looked from the point of view of a suddenly inauthentic and insecure

manhood. In them, a man might be ruined by a powerful female, a traditional femme fatale, or he might be saved by good woman, but in both cases the situation was beyond his control. Chinatown finally took a look through the other end of the telescope, imagining what the general collapse of manhood might mean for women.

As screenwriter Robert Towne has said, Evelyn Mulwray is the only

character in the film who operates out of purely decent motives, trying

to rescue herself and her daughter from the clutches of a rancid,

decayed patriarchy. The protagonist of the film, private eye

Jake Gittes, is a decent enough fellow but impotent when it comes to

helping, much less saving, her.

We’re not quite dealing with a feminist perspective here — we’re still

looking at the mess from a male viewpoint, assessing the male’s failure

of responsibility rather than exploring the female’s search for empowerment —

but we’re a long way from the phallocentric cry of male bewilderment and pain that

was at the heart of film noir.

Still, the deconstruction of the traditional femme fatale

is very thorough and deliberate, because Evelyn Mulwray is first

presented as a kind of spider woman, with all the generic clues that

used to alert us to the fact that the woman in question was going to be

trouble . . . and that’s how Gittes constructs her. The big

switcheroo is that Evelyn is in much more trouble than she has the

capacity to cause anyone else, that it’s her father’s fault and that

Gittes isn’t smart enough or strong enough to deliver her from it.

Towne’s conversation with the noir tradition is very elegant and profound. He goes back, in the film, to 1937, to the hardboiled detective fiction out of which film noir mutated, and deconstructs the “tarnished knight” of that form, locating in him the existential nullity of the film noir protagonist. Gittes has Phillip Marlowe’s private code of nobility, his commitment to a kind of rough justice, but it’s not enough anymore. The only real nobility he has left is his ability to recognize the cost of his own impotence.

When his associate speaks the film’s famous last line to him, “Forget

it, Jake — it’s Chinatown,” we know he won’t, we know he can’t.

He lives there now — and somehow, because of his failure, we all do.