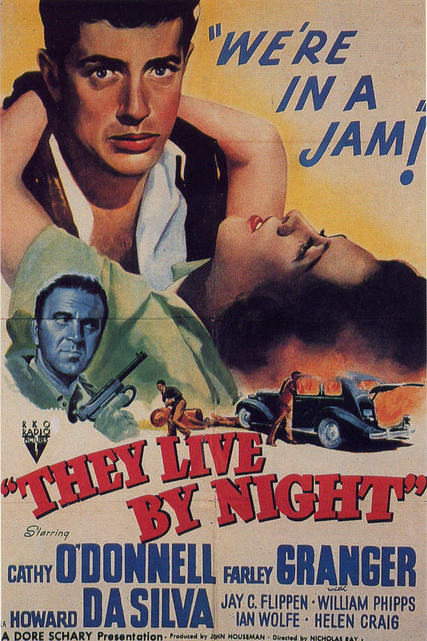

This film has to rank with Erich Von Stroheim's Blind Husbands and Orson Welles' Citizen Kane as one of the most astonishing directorial debuts in the history of American cinema. It's one of the greatest of all films noirs yet also a film that looks forward beyond noir to the various traditions that would supplant it.

Like Out Of the Past, They Live By Night

is at its core a love story. Both are hopeless love stories, but

for different reasons. In the former, fate and moral confusion

suggest a universe in which men and women can no longer co-operate —

in which love and passion have become recipes for disaster. In

the latter, the love at the film's center is the only good thing left

in a world that has become bewildering and malevolent.

You could say that Out Of the Past

represents the worldview of the generation of men who fought WWII and

came home with a feeling that the world didn't make sense anymore — that

there was a permanent disconnect between the central experience of

their lives and the society they now had to become a part of. They Live By Night,

by contrast, represents the worldview of the next generation, which

would have to live with the consequences of this post-war moral

bewilderment.

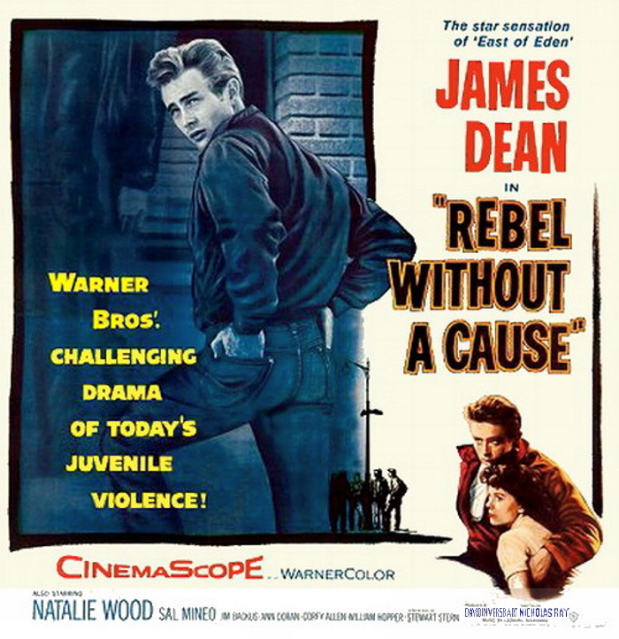

Noir historian Eddie Muller, among others, has pointed out that the Granger and O'Donnell characters in They Live By Night

are in some sense models for the Dean and Wood characters in Nicholas Ray's later Rebel Without A Cause — that in his first film Ray was starting to invent the idea of the 50s movie teenager. The Granger and O'Donnell characters are not, in fact, teenagers, but they are as innocent and bewildered as teenagers

— and their “rebellion” is just as unconscious, as instinctive, as the

rebellion in the great teen dramas of the 50s, best exemplified in

Rebel Without A Cause.

In 1947, when Ray made They Live By Night, the noir crime

thriller was the only kind of film that allowed a Hollywood director to

deal explicitly with the kind of alienation and despair that Ray

clearly saw as major elements of post-war American life. By the

time he made Rebel Without A Cause,

in 1955, he realized that he could deal with these elements in the context of

ordinary American middle-class life. That in itself was a sign

that film noir was coming to the end of its usefulness as a form — filmmakers could explore the noir sensibility anywhere, and deal with its nature and causes more directly.