The films below are sometimes called films noirs but they make up such a distinct category that they're almost always qualified with the the sub-label docu-noirs:

House On 92nd Street

The Racket

Call Northside 777

Panic In the Streets

Border Incident

The Narrow Margin

Mystery Street

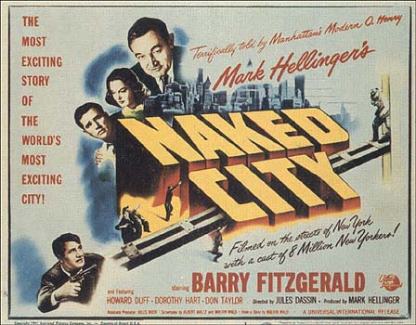

Naked City

Arson, Inc.

Loan Shark

Fingerprints Don't Lie

F. B. I. Girl

Portland Expose

A Bullet For Joey

In fact they're

all police or government-agency procedurals (or, in one case, a newspaper procedural.) They usually feature some

highly positive documentary-type footage about the law enforcement

group involved and are sometimes shot within the

facilities of the institutions they depict. (The newspaper procedural, Call Northside 777,

about a crusading journalist who saves an innocent man from prison, was

based on a real case and shot on some of the locations where the original incidents occurred.)

These films are designed to show the effective functioning of

government agencies or other establishment organizations, and while this sort of reassurance may have

addressed the same strain of post-war anxiety that film noir explored, it obviously did so from a completely different perspective than you find in the classic film noir, where suspicion of all social institutions is part of the general atmosphere of dread.

In the films above, the city may well be a dark and threatening maze,

but we enter it in the company of an upright guide, backed by the full

force of the official society, and we overcome the danger we face there

— we clean up the mess.

These films make up a vigorous genre in themselves and have become

fascinating social documents — but I don't think it makes any sense to

call them films noirs.

[The noir credentials of the films above are as follows . . .

House On 92nd Street, Call Northside 777 and Panic In the Streets are part of the Fox film noir DVD series . . . The Racket,

Border Incident, Mystery Street and The Narrow Margin are part of the Warner film noir DVD series . . . A Bullet For Joey is part of the MGM film noir DVD series . . . Naked City is found on almost all lists of films noirs . . . the rest are included in the VCI Forgotten Noir DVD series.]