There

was a great middleweight fight in Atlantic City last night between the

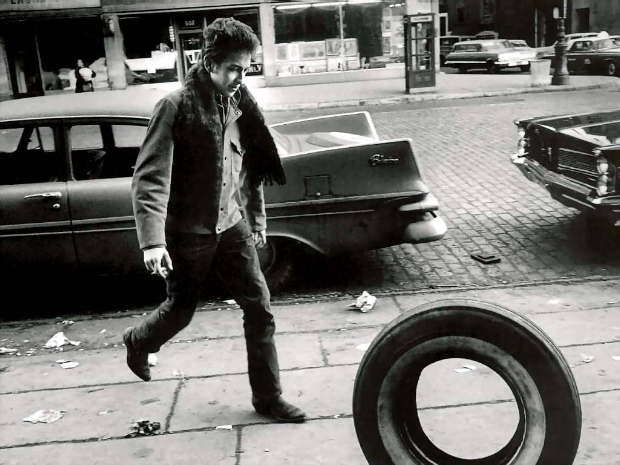

champion Jermain “Bad Intentions” Taylor from Little Rock, Arkansas, and challenger Kelly “The Ghost” Pavlik (above) from

Youngstown, Ohio. It was great because it had a three-act

narrative structure with bold contrasts and startling turn-arounds, and complicated emotional themes.

Taylor gained the championship and kept it for a while with workmanlike

victories that never seemed to challenge him in any profound way — to

test his character. People started to think he was a champion

merely faux de mieux.

Pavlik was a relatively inexperienced fighter with an unbeaten record

and a powerful punch. The punch made it a fight fans might get a

bit excited about — the inexperience made it a fight that Taylor's

handlers weren't afraid to make.

In the first act of the drama, Taylor's handlers looked wise.

Pavlik was aggressive coming out, using his jab well, but sloppy on

defense. In the second round he paid for his sloppiness when

Taylor put him to the canvas with a flurry of hard, flush

punches. Even when he managed to get up again, Pavlik looked like

he was out on his feet. But he dodged and clinched, weathered a

few more terrifying blows and managed to survive the round.

But he actually did much more than survive. When HBO commentator

Larry Merchant asked him after the fight how he felt down there on the

canvas, Pavlik replied, “You want to know the truth? I thought,

'Shit, this is going to be a long night.'” He was already gearing

up for what he had to do to stay in the contest.

What he did was recover quickly in the next round, worrying Taylor

constantly with a hard, accurate jab. The worry was just enough to

keep Taylor from using his faster hands and superior boxing skills to

wear Pavlik down or catch him again with a terminal combination.

Pavlik grew stronger round by round — Taylor didn't fade exactly, he

just never found a way to step things up from his end.

Finally in the 7th Pavlik hit Taylor with a right that stunned

him. Pavlik didn't hesitate — he closed in and beat Taylor

nearly senseless. Pavlik didn't lose his head at that point,

either. He paused, thought about it for a moment and delivered a

clincher — an upper-cut that sent Taylor to the canvas, defenseless,

at which point referee Steve Smoger stepped in and called an end to

things, not a moment too soon.

Ironies abounded. Taylor had fought one of his best fights ever,

delivering the kind of excitement that fans found lacking in his

earlier victories. But when he had Pavlik hurt in the second he

lost his focus, couldn't summon the composure to put him away, as

Pavlik did in the seventh. The less experienced fighter showed

more ring savvy than the veteran.

Youngstown was a steel manufacturing city, once upon a time, but all

that is in the past. Now it's rusting and suffering. It has

produced more than its share of boxing champions, including the

incendiary Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, and now it has new champion in

Pavlik. It must seem like a miracle — like a ghost rising from

the rust.

What a story — what a fight.