World War Two was a “good war”. America and its allies pulled together

and destroyed the Axis powers. On balance, and in retrospect, it

has to be considered one of the great achievements of

humane civilization. But human beings don’t live on balance or in

retrospect, particularly where war is concerned. They live inside

the horror of it and it takes a toll on individuals and on societies

which can never be fully measured.

The upbeat spirit of American propaganda during the war, and the

genuine satisfactions of victory, veiled the true experience of the war

for millions — not just for those who fought it on the battlefields of the

world, but for those at home who lived in terror that their loved ones at

the front might never return . . . and of course, most especially, for those at home whose loved ones didn’t return. On a broader level, anyone who simply witnessed

the spectacle of total war on a global scale, from whatever distance, had

to have experienced a soul-shaking anxiety about the fragility of all

social structures and cultural norms.

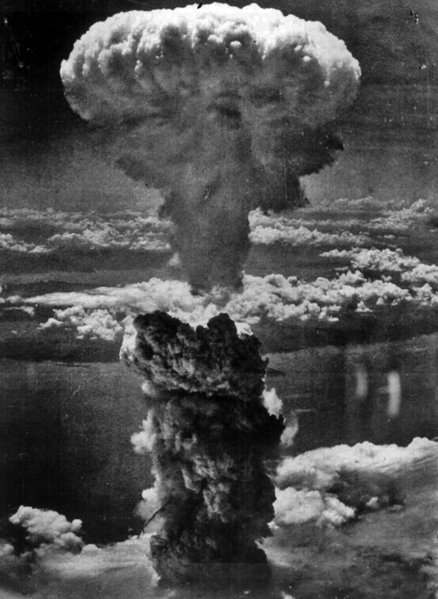

After WWII, the whole planet experienced post-traumatic stress disorder

— localized in this case by the fact of the atomic bomb, which ended

the war but left the world with a paradox that wouldn’t go away.

It took an act of colossal horror to finally “win” this good

war. And the prospect of this horror being again visited on the

world was far from unimaginable.

We now know a lot more than we used to about post-traumatic stress

disorder and the ways it can be treated. In the immediate post-war era, the

phenomenon was more elusive, and often unrecognized. We made

meaningful social restitution to the veterans of the war, with measures like

the G. I. Bill — we reconstructed the devastated nations we

conquered. But that just scratched the surface.

It was in art that the true psychic cost of the war was exposed and explored — nowhere more pointedly than in film noir. The sort of trauma that engenders PTSD is identifiable by several characteristics — a sense of being out of control and confused, a

sense of terror, a sense of being outside the normal realm of human

experience. Is there a better description of the usual

predicament of the protagonist in a classic film noir?

PTSD on a broad cultural and societal level is what best explains the phenomenon of film noir, which on its surface is so mysterious. Why should a triumphant

nation, after a great collective victory in a good war, have been

gripped by that mood of existential dread which informs so many Hollywood films of the post-war era? Why should the most spectacular achievement of American arms have led

to a crisis of manhood, a sense of impotence, a fear of powerful women

incarnated in the morbid fantasy of the femme fatale?

Film noir was a dream landscape where the buried costs of WWII could be recognized, reckoned and mourned, as a prelude to psychic recovery, or at least psychic survival.

Veterans of combat often report the difficulty of dealing with people

who have not shared their experience of it — people who can never

really know what it’s like. Film noir, far more than the WWII combat film, was one of the few arenas of American life where the true legacies of war, its lingering moral and

psychological dislocations, could be engaged without apology or shame.