“Lloyd, no! No!”

“He told me he was going to wear that costume for Halloween, but I didn't believe him. The fool. The mad fool!”

“Lloyd, no! No!”

“He told me he was going to wear that costume for Halloween, but I didn't believe him. The fool. The mad fool!”

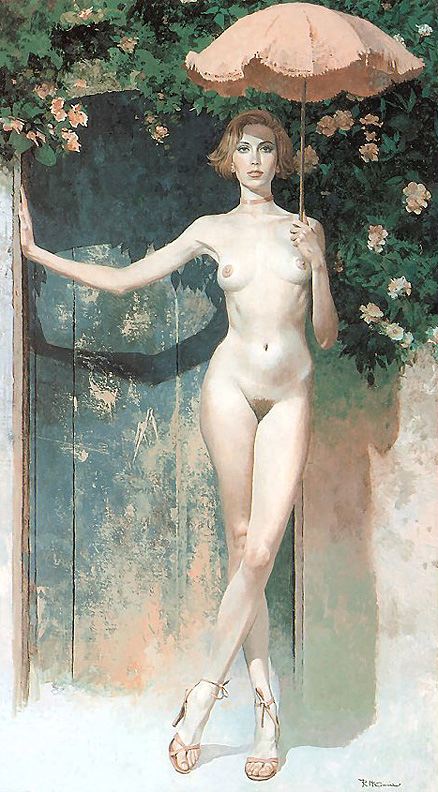

The women on Robert McGinnis'

paperback covers were often scantily clad, looking as though they might

slip out of whatever they were wearing at any moment, but he also did

straight-ahead nudes. The modest parasol here, warding off the

sun's gaze, gives this example a certain teasing piquance.

I fell in love with Mary Pickford when I watched this film a few years ago. I know you’re

probably thinking, “What took you so long?”, but I really hadn’t seen

much of her work before — some of the Biograph shorts she made for D.

W. Griffith and Sparrows, one of her later silents. I liked Sparrows a lot, thought it was a very well-made film, and admired Pickford’s craft extravagantly . . . but there was something self-conscious about it, something built into the idea of a masterful

artist playing a child, which had the flavor of a brilliant (a really brilliant) stunt.

But when I watched Amarilly Of Clothesline Alley all my resistance

melted. First of all, Pickford plays a sexually mature female, innocent

by choice but well aware of her options — and she’s very sexy, very

self-possessed and powerful, which makes her goodness all the more

vexing. The whole film is permeated with a strong aura of female power,

expressed most poignantly and convincingly in the easy camaraderie

between Amarilly and her mother — you get a sense that there’s no

problem on earth these two can’t solve . . . and haven’t solved, in a

sense, keeping a fatherless family together in crushing poverty. (You

also get a clear echo of Pickford’s actual early life, growing up too

fast, more of a peer than a daughter to her own mother.)

The wry eye they throw on the rest of the world, especially the world of

men, delightfully underlined in the snappy intertitles by Frances

Marion, their exuberant enjoyment of each other’s company, and of life

itself, exactly as it is, suggest a whole universe of female

self-sufficiency and dominion which our culture has managed to

eradicate almost entirely from the mainstream of popular art. (I begin

to think that the national euphoria over Pickford’s marriage to Douglas

Fairbanks may have reflected America’s pride, and perhaps relief, that

the country managed to produce a man worthy of her.)

The style of the film as a whole, and Pickford’s performance in particular,

is shockingly casual, fast-paced, breezy and naturalistic — Amarilly

seems to have a whole and real and complicated inner self which she

chooses to share with others, and with us, out of sheer generosity and

goodwill. Virtue has never seemed so alive, so glamorous.

Well, I’m not the first person this has happened to, and thanks to the miracle of DVDs, I won’t be the last.

Over at the Alternative Film Guide, Andre Soares has a wonderful appreciation of Deborah Kerr (who died recently at the age of 86) in which he tries to unravel the mystery of her subtle erotic appeal. Such mysteries are ultimately unravel-able, of course, but Soares comes close, and reminds us why Kerr’s performances are always so alive and vexing.

I’ve written about her previously in a review of The Sundowners.

These, in the day when heaven was falling,

The hour when earth’s foundations fled,

Followed their mercenary calling,

And took their wages, and are dead.

Their shoulders held the sky suspended;

They stood, and earth’s foundations stay;

What God abandoned, these defended,

And saved the sum of things for pay.

The title of this poem is Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries.

It’s one of my favorite poems of all time because it looks at things so

coldly and reminds us that sincerity is not the highest of

virtues. Today we tend to think of virtue as a state of mind —

if you mean well, you’re a good person. To Housman, as to the ancient Greeks, virtue was action, pure and simple.

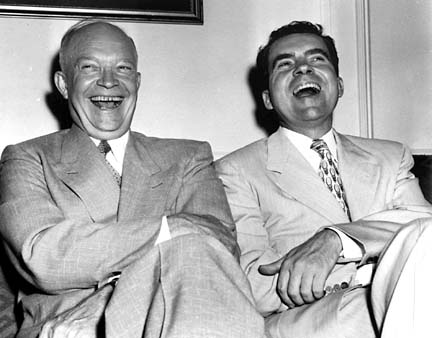

When he died in a car crash this Spring, David Halberstam had just finished his 21st book, The Coldest Winter,

an epic study of the Korean War. It's partly a work of military

history, with combat narratives based on interviews with veterans of

the conflict, but its greater value lies in the way Halberstam places

the war in the context of the post-war world, of American and global politics and strategy.

It fills in yet another piece of the puzzle of America's mood after

WWII — dark, anxious, bewildered, unsure of its new role as a world

superpower, veering between arrogance and lunatic paranoia.

There are many lessons for our own times to be learned from the book —

not least about the ways the Republican party managed to box the

Democrats into policies they mistrusted under the threat of being labeled

“soft on Communism”. Substitute “terrorism” for “Communism” and

you will see the same dynamic at work today.

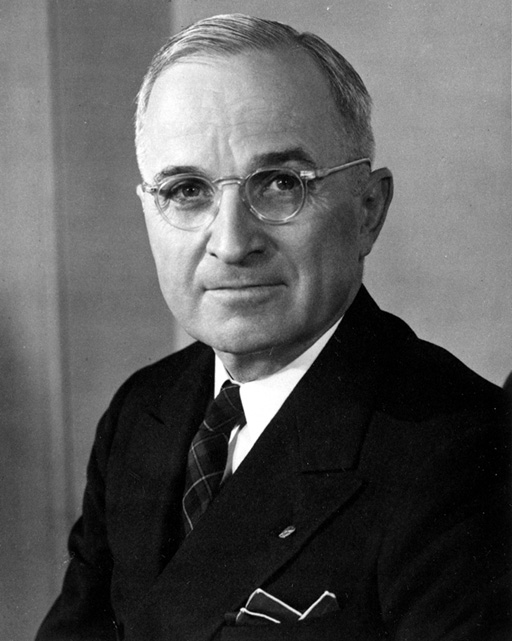

The war in Korea all but wrecked Truman's presidency, but he was

confident that history would judge him more kindly than his

contemporaries, as indeed it has. Among the high-ranking soldiers

and politicians, Matthew Ridgway and Truman emerge in Halberstam's book

as the true heroes

of the war. Ridgway learned how to fight the Chinese because he

was willing to take them seriously, to respect them as soldiers,

something the racist high command under MacArthur could not do.

Truman was willing to buck popular sentiment and

risk political ruin to oppose MacArthur, whose madness served the purposes

of the right-wing Republicans in Washington but whose insubordination

threatened the very core of the American system of government, the principle of

civilian control of the military.

Among the boots on the ground, there were heroes by the thousands,

though they got no glory out of it, or even much recognition from the

folks at home. Korea was a war Americans wanted to forget, even

while it was happening — which is just the kind of war that needs to

be remembered and studied with care. We're in one like it

right now — part of the price a nation pays for forgetting the

grievous mistakes it has made in the past.

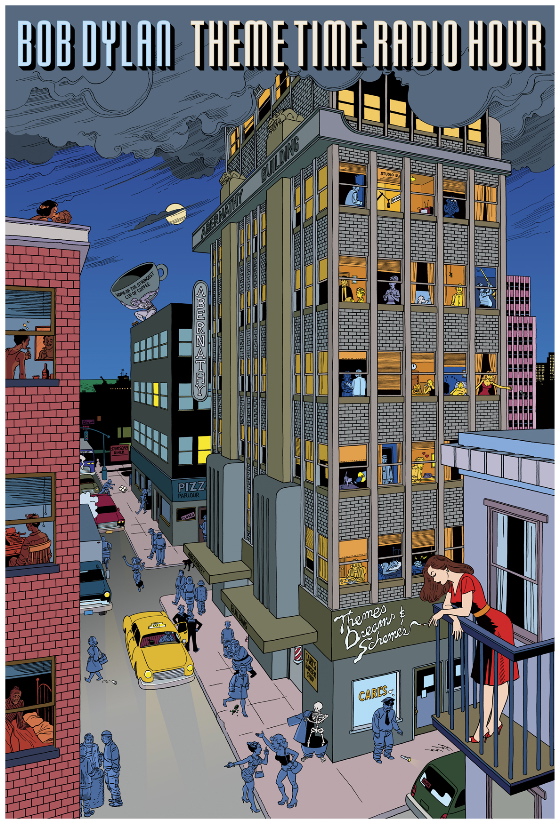

This is a poster designed by Jaime Hernandez, of the awesome comics duo

Los Bros Hernandez, for Bob Dylan's great show on XM Satellite Radio,

which might be the best radio music show of all time. Each week

Dylan plays songs he likes on a given topic. The songs are great,

but it's also great to see how Dylan organizes music in his mind.

It's much the way he organizes images in his songs — according to

associations and affinities that don't follow conventional rules or

categories.

I don't listen to the show much because like more and more people these days I have a hard

time dealing with scheduled entertainment — unless it's something live

like a baseball game. If it's digital and I can't download it or

get a copy of it to enjoy at my leisure, it's too much trouble, too

annoying — too much about the convenience of the provider and not

enough about my convenience.

[With thanks to Boing Boing for the link.]

It is in the rock, but not in the stone;

It is in the marrow but not in the bone;

It is in the bolster, but not in the bed;

It is not in the living, nor yet in the dead.

This is a riddle, of course. Can you guess the solution?

[From I Saw Esau, edited by Iona and Peter Opie.]

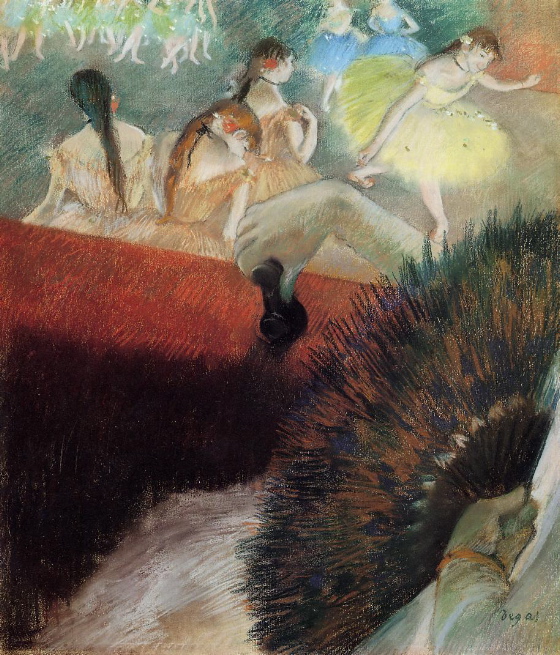

Degas' work is an odd combination of academic and Impressionist

strategies. His draftsmanship tended to be rigorous, almost

photorealistic — he often worked from photographs — and he shared the

academic's preoccupation with the dramatic, expressive possibilities of

space. At the same time his surfaces shimmered with a life of

their own, in the Impressionist way, creating a powerful counter

tension.

The image above is very unusual. The design offers a bold

recession of spaces, in three dramatic stages, while the treatment of

the surface flattens it all out again, as in a Japanese print, also a

strong influence on Degas' style.

I can never feel comfortable calling Degas an Impressionist, but he wasn't an academic, either. He was just Degas.

Fear no more the heat o' the sun,

Nor the furious winter's rages;

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta'en thy wages;

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

Fear no more the frown o' the great;

Thou art past the tyrant's stroke:

Care no more to clothe and eat;

To thee the reed is as the oak:

The sceptre, learning, physic, must

All follow this, and come to dust.

Fear no more the lightning-flash,

Nor the all-dreaded thunder-stone;

Fear not slander, censure rash;

Thou hast finished joy and moan;

All lovers young, all lovers must

Consign to thee, and come to dust.

No exorciser harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Nothing ill come near thee!

Quiet consummation have;

And renownéd be thy grave!

I've always loved this song, from Cymbeline, one of Shakespeare's late plays, especially this couplet:

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

It's so

Shakespeare — speaking of the gravest things in the lightest and most

lilting way. I can't help but see it as a reflection of the

country humor Shakespeare grew up with, when hard things, all too

familiar, needed to be tossed off carelessly at times — sort of like

the phrase “he bought the farm.”

At any rate, the tone echoed through English literature — A. E. Housman derived a whole oeuvre from it, as in the following:

With rue my heart is laden

For golden friends I had,

For many a rose-lipped maiden

And many a lightfoot lad.

By brooks too broad for leaping

The lightfoot boys are laid,

The rose-lipped girls are sleeping

In fields where roses fade.

I also love the image in this couplet from Shakespeare's song:

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta'en thy wages . . .

Though

Shakespeare became a wealthy man and a speculator later in his life, he

never got too far, imaginatively, from his working-class roots.

Life to him was always a job of work, literally and

metaphorically. He died soon after giving up his trade as a

playwright — in his heart, I suspect, the end of work and the end of

life were more or less the same thing, as they were for most English country folk of the time.

It took me a while to realize where the image in the couplet above

comes from, specifically — Saint Paul's letter to the Romans, where

the apostle writes, “The wages of sin is death.”

Saint Paul didn't exactly mean that death was a punishment for sin,

or that if you lived a sinless life you could escape death, because no one can live a sinless life. He

was just making a general observation, as Shakespeare was, about the

condition of man, imperfect by nature, doomed to die. When you

take your last wages in this world, all you can buy with them is the

farm.

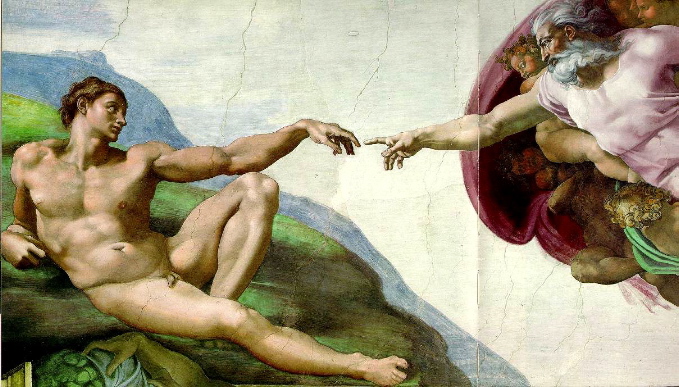

A guy is talking with God and he says, “God, what is a million years to you?”

God says, “A million years is a second to me.”

The guy says, “God, what is a million dollars to you?”

God says, “A million dollars is a penny to me.”

The guy says, “God, could I have a penny?”

God says, “Sure — just a second.”

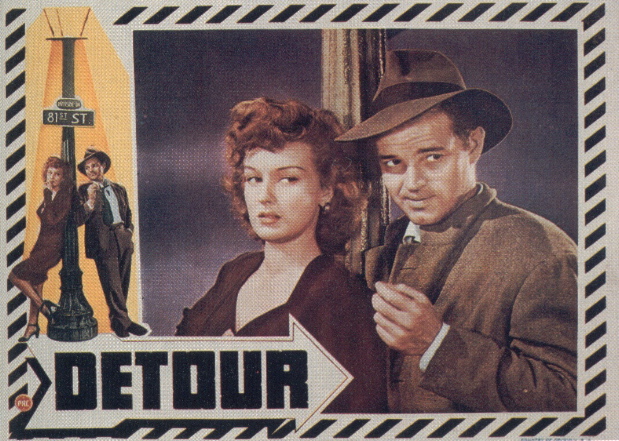

Although, as I wrote earlier, I don't see film noir

as expressly concerned with theological issues, there is a

sense in which the idea of “the death of God”, as a kind of

metaphorical expression for existential bewilderment, gets close to the

heart of the tradition.

Edgar G. Ulmer's Detour, a low-budget thriller from 1945, was arguably the first true film noir.

It offered a vision of the world as a moral maze from which there was

no exit — an image that accorded well with the unconscious dread which

gripped America in the wake of WWII and in the shadow of nuclear

apocalypse.

In this light, it's interesting to look at Ulmer's The Black Cat,

a strange Universal “horror film” from the early 30s. There, the

source of the horror that ensnares its innocent protagonists is a

modernistic version of the old dark house — which sits on the site of a

ghastly battle from WWI, somehow infected by the mass slaughter that

took place there.

This may not be enough to prove that Ulmer saw a connection between the moral chaos of Detour and the horrors of WWII but it certainly suggests

that there may have been an unconscious association of the two

ideas in Ulmer's mind.

Certain modern commentators want to see film noir

as a phenomenon with essentially political implications — something

that's not hard to argue given the leftist leanings of many of the

great masters of the noir tradition, a number of whom were eventually blacklisted. But seeing film noir

as essentially political expression I think sells the phenomenon short. Film noir reflected

an existential dread far deeper than politics could encompass.

“The death of God” gets closer to expressing this than “the corruption

of Capitalism”.

Curiously enough, the French critic Luc Mollet said that Ulmer's whole body of work

expressed “the loneliness of man without God”. A recent essay on

Jules Dassin's Brute Force, included in Criterion's DVD edition of the film,

quotes Mollet dismissively and ironically, suggesting that he was just

offering a kind of smokescreen for the political underpinnings of the noir vision. But I think it makes more sense to see the nutty, irrational Stalinism of many noir

filmmakers as a smokescreen for the more comprehensive psychic

dislocations of post-WWII America, in which Communism and Stalinism

were just faddish, ill-conceived replacements for a God who seemed to

have abandoned the world in the desert outside Los Alamos, New Mexico,

after clearly announcing, at places like Auschwitz, his plans to retire

permanently from the world's affairs.

If film noir were simply a

reflection of the politics of its leftward-leaning makers, it ought to

be terribly dated today, after the demystification of Communism and

Stalin, those ephemeral shibboleths for which the Hollywood radicals martyred

themselves. But film noir

still speaks to us as strongly as it ever did — perhaps because “the

loneliness of man without God” still troubles the spirit, while the

passing of Stalin and Communism go conspicuously unlamented.

[Thanks again to Tony D'Ambra of films noir whose posts on film noir and the death of God prompted the thoughts above — and to Michael Mills' classic film blog for the Detour advertising art.]

Émile Friant painted portraits and scenes of the French countryside. He

had, to me, a decidedly cinematic eye — his genre paintings are not

sentimentalized and they have a bold, dynamic quality based on spatial

compositions of great though subtle power. They remind me of Bertolucci’s

images in 1900.

The painting above uses a technique Tissot was fond of — creating a

space in the foreground that instantly occupies one’s attention but

which also opens up into a deep space beyond. Spaces opening up

into deeper spaces instantly summon up the idea of movement, of the

potential for movement — they almost produce a sensation of movement. This

and their photorealistic quality are what to me give them a cinematic

quality.

Friant was a late Victorian — he lived until 1932, well into the era

of the Impressionist triumph. Like John Singer Sargent he

borrowed a freer approach to brushwork from the Impressionists while

remaining true to the basic aesthetic ideals of the Victorian academy.

In

a comment here (and currently on his own web site films noir) Tony

D'Ambra posts an intriguing quote from Mark Conrad about the connection

between film noir and existentialism:

“My proposal, then, is that noir can also be seen as a sensibility or

worldview which results from the death of God, and thus that film noir

is a type of American artistic response to, or recognition of, this

seismic shift in our understanding of the world. This is why Porfirio

is right in pointing out the similarities between the noir sensibility

and the existentialist view of life and human existence. Though they

are not exactly the same thing, they are both reactions, however

explicit and conscious, to the same realization of the loss of value

and meaning in our lives.”

[This is from Conrad's book The Philosophy of Film Noir: Nietzsche and the Meaning of Noir: Movies and the ‘Death of God’.]

I agree with the gist of the quote, and with Tony's assertion that film noir

and existentialism have a lot in common — though I'm not sure

that there was a direct influence on the former by the latter. I

think Conrad is on the right track when he locates the essence of film noir in a particular moral orientation to the universe and not in a style or in subject matter.

I'm also not sure that the death of God is quite the right way to explain film noir, though — except as a metaphor for “the loss of value and meaning in our lives”. Film noir,

to me, is more about moral bewilderment as a social phenomenon, with

social causes, than about loss of faith in God. It's about male

insecurity and fear of women, about a creeping dread that the world

isn't what it seems to be, doesn't work anymore — if it ever did.

These sorts of feelings have theological implications of course, but

they don't lead automatically to atheism or to existentialism — not in America, with its

strong Protestant tradition, which has always preached what the

theologian Paul Zahl calls a “low anthropology”, holding that the world

is intrinsically corrupt, redeemable only by supernatural Grace.

Hitchcock's The Wrong Man is an apt illustration of what I mean. The film is pure noir

— except in its denouement, when the protagonist is saved not by a

good woman or luck or some kind of desperate action but by the direct

intervention of Jesus. This is not a whole lot more improbable

than the ways some other protagonists get saved in the film noir tradition.

We needn't go this deep, however, to find the core, and the enduring appeal, of film noir.

The feelings it deals with, though brought to the surface by the

peculiarly horrific experiences of the generation that suffered through

WWII and afterwards lived in the shadow of nuclear annihilation, are

common to all men and women at some moments of their lives.

Such feelings may lead to atheism, to philosophies like existentialism

— or to religious epiphanies like the one Saul had on the road to Damascus. Because film noir

is art, not theology or philosophy, it is not concerned with such

outcomes. It is only concerned with the feelings, with certain particular conditions of the heart — with bringing

them to the surface and allowing us to engage them.

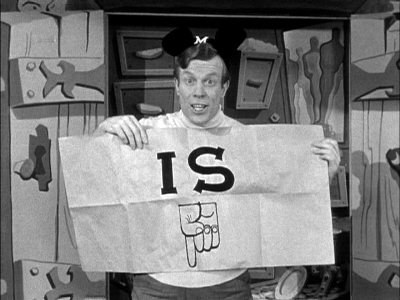

We sometimes think of the Fifties, the Eisenhower years, as a time of

blandness, naive optimism and conformity. As a kid in the Fifties

that’s how it seemed to me — I took everything at face value. I

was a member of the Mickey Mouse Club — I had the ears.

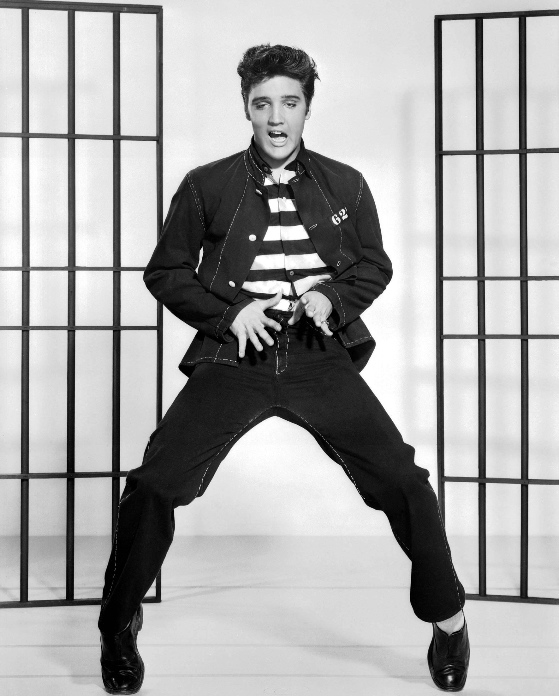

Looking back today at the popular culture of the Fifties, with wiser

eyes, perhaps, the picture is much different. The sunny side of

things looks like the thinnest of veneers. Film noir

flourished in the Fifties. Pulp fiction got unspeakably bleak and

harrowing. The subversive sexuality and energy of rock and roll

bubbled up from the black underclass with astonishing ferocity.

Some white performers tried their best to tone it down, but it stayed

dirty. Ed Sullivan could present it as a kind of vaudeville

novelty act, but kids knew better — soon it would become the

soundtrack for everybody’s life.

The Beats had already started turning on and dropping out, in an unsettling but

compelling rehearsal for the Sixties. At the time it seemed like a bizarre aberration.

The film cycle depicting middle-class teen-aged angst and rebellion was born.

A girl to the Brando character in The Wild One: “What are you rebelling against?”

Brando: “What have you got?”

Low-budget sci-fi movies retailed images of apocalypse by the score.

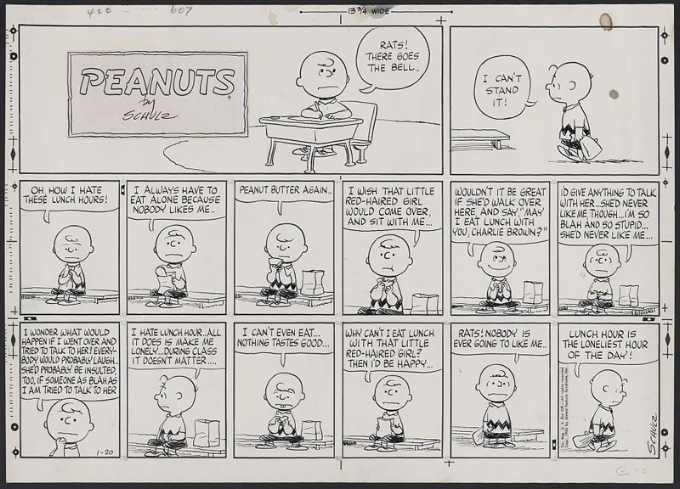

Even the kinder, gentler manifestations of popular culture reveal, on

closer examination, dark undercurrents. Charles Schulz said this

of his mildly satirical comic strip Peanuts:

“All the loves in the strip are unrequited; all the baseball games are

lost; all the test scores are D-minuses; the Great Pumpkin never comes;

and the football is always pulled away.”

And consider the apparently frivolous comic visions of Frank Tashlin —

which are, if examined closely, savage deconstructions of popular

American culture.

Indeed, the more you look at Fifties culture the more it comes to seem

that those mouse ears weren’t at the heart of it — they were

distractions from a deep national anxiety, a brooding sense of dread that permeated everything.