Through

the good offices of Joe D'Augustine, of the excellent Film Forno web

log, I was recently able to view André de Toth's remarkable film Pitfall, from 1948.

Joe thought I might find it an interesting example of domestic noir

— and on many levels that's just what it is . . . a taut, harrowing

thriller about a man whose good marriage is threatened in violent ways

by a moment's indiscretion. The film's tough, snappy, cynical

dialogue bears favorable comparison with the dialogue in Double Indemnity — and the moral confusion of the protagonist, played by Dick Powell, is pure noir. (We also get to see Raymond Burr in one of his earliest noir villain roles.)

But there's something unusual about this film — something that distinguishes it from true noir and from the films I think of as domestic noir. It's the way that the institution of marriage, and the women in the film, are portrayed.

Lisbeth Scott, in what ought to be the femme fatale role, isn't fatale

at all, in the end. She's the victim of male obsession and

mendacity, who's destroyed when she tries to strike back. What's important, though, is that we see

the predicament she's in from her point of view — not from the point

of view of the men who don't understand her or fear her, as we would in

a classic noir.

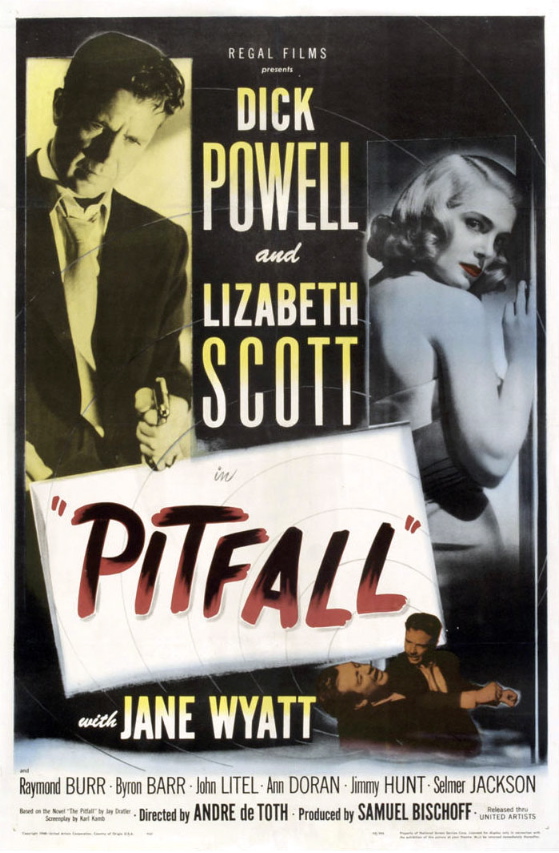

(The oddness of this is only reinforced by the copy on the lobby card

above, which tries to sell the Scott character as a typical femme fatale — assuming that that's what audiences of the time were looking for.)

More remarkably, Powell's wife in the film, wonderfully played by Jane Wyatt, is a

true partner — neither delivering angel nor destructive goddess, the

two poles of womanhood in the classic noir. Pitfall

offers one of the best and most convincing portraits of a good marriage

in all of cinema — which takes it far from the rancid view of married

life found in almost all domestic noirs.

This film, in fact, presents marriage as a viable refuge from the moral

maze, the existential dread, of post-war American life — and it does

so without a trace of piety or sentiment. Like young Charley in Shadow Of A Doubt, Powell's character in Pitfall

feels trapped by family life at the beginning of the film — only to

discover in the end that it's the only thing in his life that makes any

sense at all. It's a way out that's almost always denied to the protagonist of a classic noir, lost in the labyrinth of noir's dark city — and a view of marriage that's unknown in the moral chaos of a classic domestic noir.

I guess this film belongs in a category all its own — anti-noir.

[In honor of Pitfall I've added a new category to my Film Noir Master List — Sui Generis, for noirish films that aren't like any other films noirs. So far it has two entrants, the anti-noir Pitfall and the schizo-noir Trapped.]