As a prelude to watching Ken Burns' new film about WWII, The War,

I decided to have another look at his film about the Civil War.

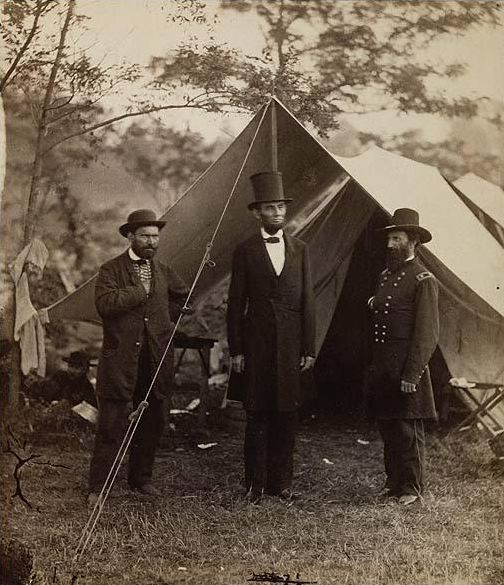

This isn't really a documentary, or a work of history — it's a poem,

made up of very beautiful words, both newly written and derived from

historical sources, of images and of music. It's in fact an

example of a new art form — a new extension of what a movie can be,

but so organic and effective that you wonder why no one ever tried it

before.

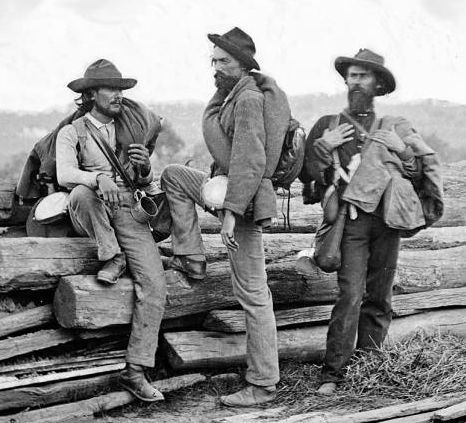

One of its glories is that it so boldly deviates from the conventional

filmmaking wisdom of its day. It constitutes a contemptuous

defiance of MTV-style cinema. MTV-style cinema is founded on the

proposition that none of its constituent images has any inherent

quality or interest — none of them is worth your serious

attention. But the resulting strategy is to simply bombard you

with vaguely engaging images which pass so quickly that you don't have

time to evaluate them — thus producing the impression that perhaps you

have actually seen something worth seeing. The art of it is the

art of the three-card monte mechanic. You aren't exactly the

audience for this sort of cinema — you're the sucker, the mark.

Burns, by contrast, doesn't need to use cinematic techniques to

distract you from the fact this his basic material is shabby and

second-rate — because it isn't. This allows him to step back,

let the material breathe, speak for itself.

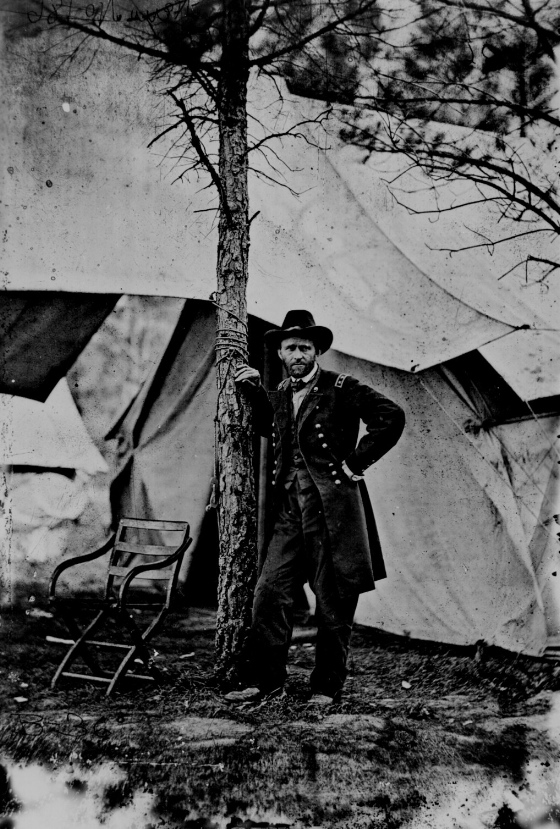

His primary technique is extraordinarily simple and extraordinarily

effective. It is simply to marry one image with one

sentence. Sometimes he will vary this rule, cutting to a new

image on a phrase ending, or showing different details of the same

image within the same sentence. Occasionally, for purposes of

emphasis or surprise, he will cut to a new image illustrating a single

word or name in a sentence.

But the primary strategy is generally maintained — one sentence,

one image. Once you get used to this, subliminally, it allows you

to absorb the contrapuntal lines of word and image in a kind of

composure of attention. There

is a third line, of course — the music. But Burns does something

unusual with that as well. He recorded the music first and then

conformed the pace and tone of the spoken quotes and narration to the

music, and adjusted the images accordingly.

The result is dense and many-layered — each line of Burns' film has a

life and momentum of its own and does not dominate the other lines . .

. but it has the wholeness and integrity and logic of a fugue.

It's a remarkably fine piece of work.