Although, as I wrote earlier, I don't see film noir

as expressly concerned with theological issues, there is a

sense in which the idea of “the death of God”, as a kind of

metaphorical expression for existential bewilderment, gets close to the

heart of the tradition.

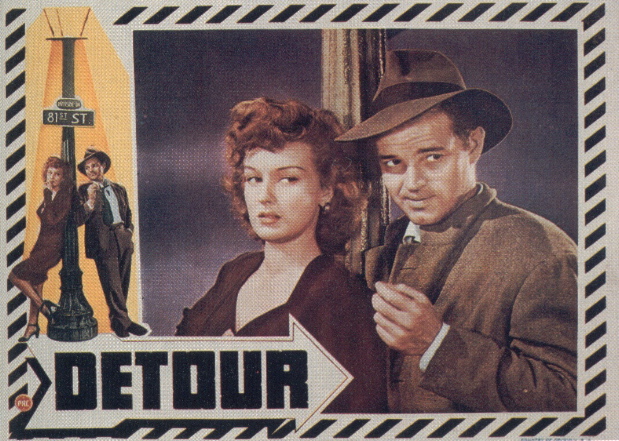

Edgar G. Ulmer's Detour, a low-budget thriller from 1945, was arguably the first true film noir.

It offered a vision of the world as a moral maze from which there was

no exit — an image that accorded well with the unconscious dread which

gripped America in the wake of WWII and in the shadow of nuclear

apocalypse.

In this light, it's interesting to look at Ulmer's The Black Cat,

a strange Universal “horror film” from the early 30s. There, the

source of the horror that ensnares its innocent protagonists is a

modernistic version of the old dark house — which sits on the site of a

ghastly battle from WWI, somehow infected by the mass slaughter that

took place there.

This may not be enough to prove that Ulmer saw a connection between the moral chaos of Detour and the horrors of WWII but it certainly suggests

that there may have been an unconscious association of the two

ideas in Ulmer's mind.

Certain modern commentators want to see film noir

as a phenomenon with essentially political implications — something

that's not hard to argue given the leftist leanings of many of the

great masters of the noir tradition, a number of whom were eventually blacklisted. But seeing film noir

as essentially political expression I think sells the phenomenon short. Film noir reflected

an existential dread far deeper than politics could encompass.

“The death of God” gets closer to expressing this than “the corruption

of Capitalism”.

Curiously enough, the French critic Luc Mollet said that Ulmer's whole body of work

expressed “the loneliness of man without God”. A recent essay on

Jules Dassin's Brute Force, included in Criterion's DVD edition of the film,

quotes Mollet dismissively and ironically, suggesting that he was just

offering a kind of smokescreen for the political underpinnings of the noir vision. But I think it makes more sense to see the nutty, irrational Stalinism of many noir

filmmakers as a smokescreen for the more comprehensive psychic

dislocations of post-WWII America, in which Communism and Stalinism

were just faddish, ill-conceived replacements for a God who seemed to

have abandoned the world in the desert outside Los Alamos, New Mexico,

after clearly announcing, at places like Auschwitz, his plans to retire

permanently from the world's affairs.

If film noir were simply a

reflection of the politics of its leftward-leaning makers, it ought to

be terribly dated today, after the demystification of Communism and

Stalin, those ephemeral shibboleths for which the Hollywood radicals martyred

themselves. But film noir

still speaks to us as strongly as it ever did — perhaps because “the

loneliness of man without God” still troubles the spirit, while the

passing of Stalin and Communism go conspicuously unlamented.

[Thanks again to Tony D'Ambra of films noir whose posts on film noir and the death of God prompted the thoughts above — and to Michael Mills' classic film blog for the Detour advertising art.]

Lloyd I am glad I somehow prompted your prolific and provocative musings on film noir of late, and I salute you for putting it out there. Sadly though, it is an essentially lonely pursuit I fear for you and the very few others who are thinking deeply about the genre outside academe.

The concern with existential angst is what attracted me to films noir, and your posts have prompted me to look at certain films in new ways. More particularly, I have always dismissed Detour as an oddity that I didn't take too seriously, mainly because the protagonist brought his fate upon himself by his own foolishness, and I saw the plot as too contrived. But now after your reading your post I feeel that perhaps, Al makes disastrous choices because he has lost a defining paradigm for life and immaturity, and an indifferent universe may have played a stronger role in his downfall, than I previously thought.

I agree that there are elements of the socio-political in many noirs: Dassin, Lang, and Wilder come immediately to mind, but I disagree with some aspects of your analysis of leftism and film noir. Many of the great European film noir directors that landed in Hollywood, fled fascism, and I see no evidence that they had any Stalinist inclinations. We must be careful not to confuse leftism with authoritarian communism.

I know you are aware of my views on existentialism and noir, but I should say that the leftist critique of the intellectual left of Europe was a response to existentialism and, yes, the death of God. For others the response was and inclination to nihilism, and yes, Stalinism. W e can see nihilism too in many noirs.

That said, I agree the political is only one element of many in the film noir genre, and placing exclusive emphasis on this element in a director's oeuvre is invalid and limiting.

I also cannot agree with your statement “Hollywood radicals martyred themselves.” They were destroyed for the most part because of past associations or beliefs that they in most cases no longer held, and principally for their innate decency and courage when they placed loyalty and morality ahead of self-interest. If they were martyrs, their sacrifice was for the highest ideals not “ephemeral shibboleths”.

Tony, thanks for these thoughtful comments.

While I deplore what was done to the Hollywood dissidents in the blacklist, and feel that the determining issue was freedom of speech and thought, a high ideal to be sure, I don't think we should lose sight of the fact that most of those persecuted were defenders of Stalin's regime, even in the face of massive evidence of his massive crimes.

They may not have been Stalin's operatives in America, as their oponents labeled them, but they had an irrational faith in the Soviet system, even under Stalin, which to me was closer to religious belief than to considered political thought.

In the era of “the death of God”, Communism became a kind of alternative faith for many. The image of Stalin as a kind of new and more authentic Jesus Christ was being retailed in Russian art as early as 1929.

Hi there, I would like to subscribe for this web site to get most recent updates, sso where can i do it please help.

Follow @Lloydville on Twitter. But know that the author died in February 2015 and the site will be used to post occasional materials that surface from the archive.