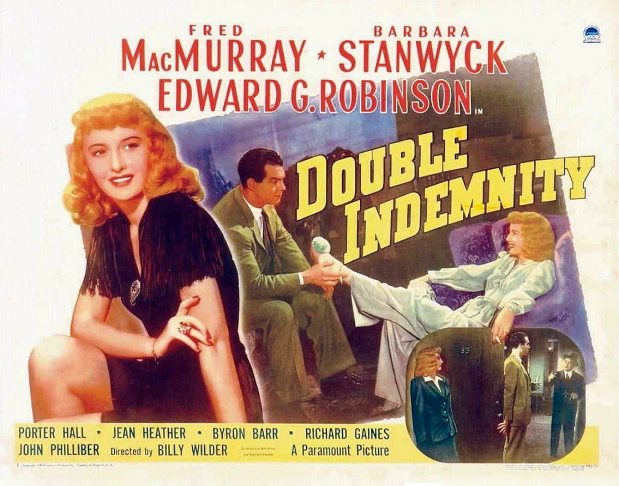

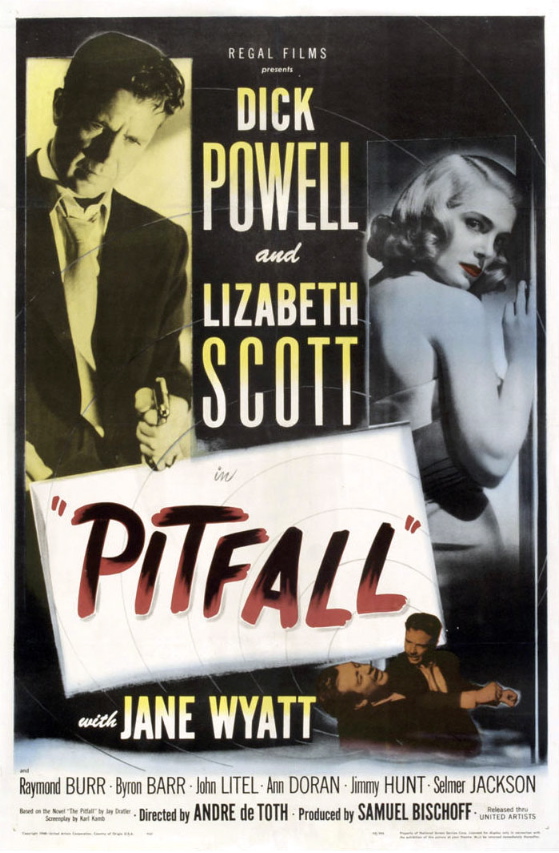

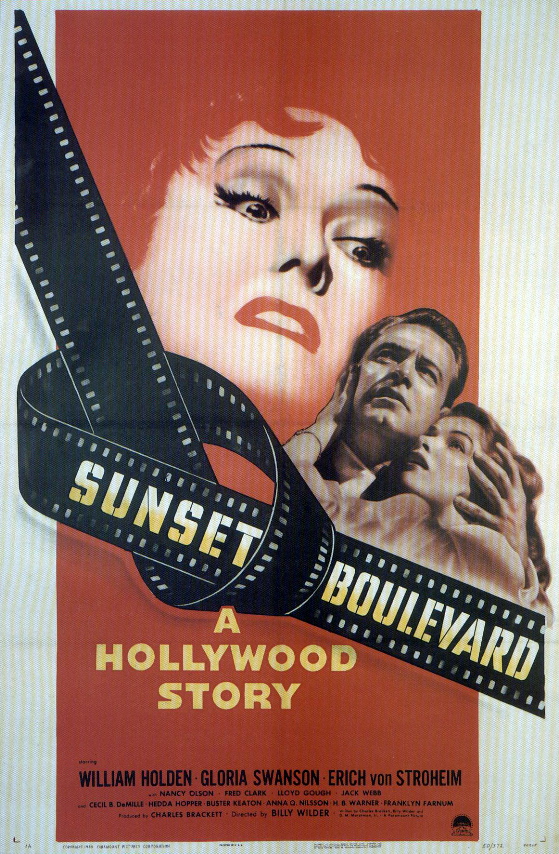

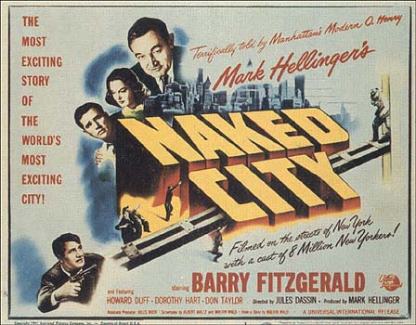

In my last post I quoted James Ellroy's brilliant summation of the message of film noir — “You're fucked.” One of the ways “you're fucked” in film noir is that most of the women you're going to meet in the shadowy backstreets of noir's

dark city are going to be smarter and stronger than you are. They

may use their power to save you, they may use it to destroy you, but

the situation is going to be beyond your control.

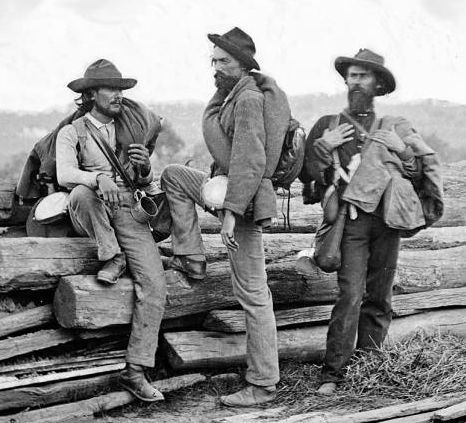

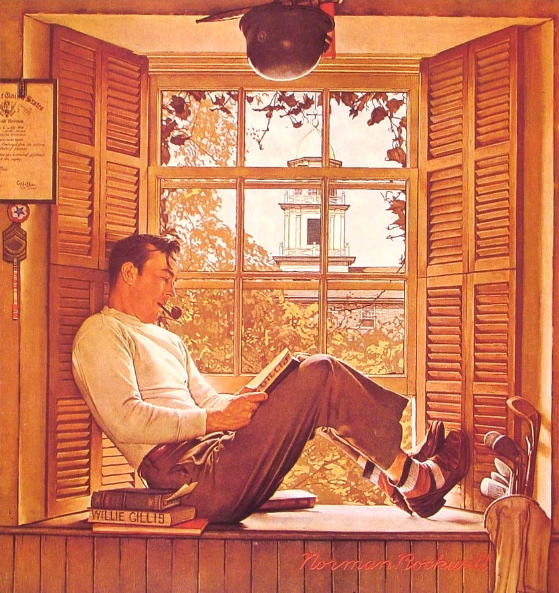

This view of women was obviously a projection of male anxiety and

insecurity in the post-WWII era. There are some extraordinary

female characters in the film noir

tradition, but usually they're not quite real — they are demons, or angels,

summoned up out of troubled male psyches. A film doesn't need a femme fatale to be noir

— they're absent in many classic films in the tradition — but it does

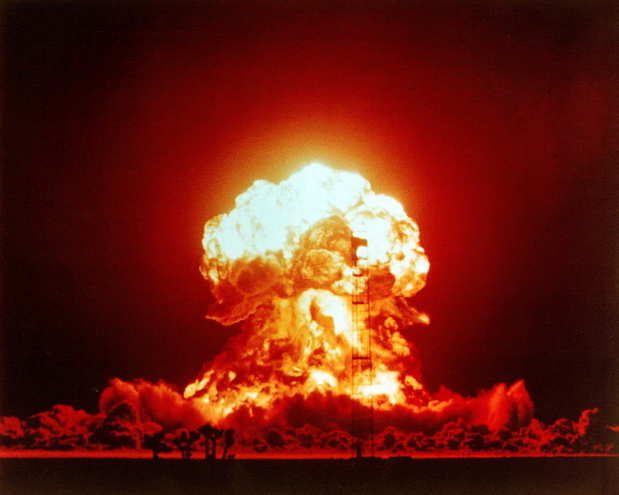

need a sense of male helplessness. It's a comprehensive

helplessness, in the face of society and the universe itself — tough,

powerful women are just one manifestation of a general existential

dread.

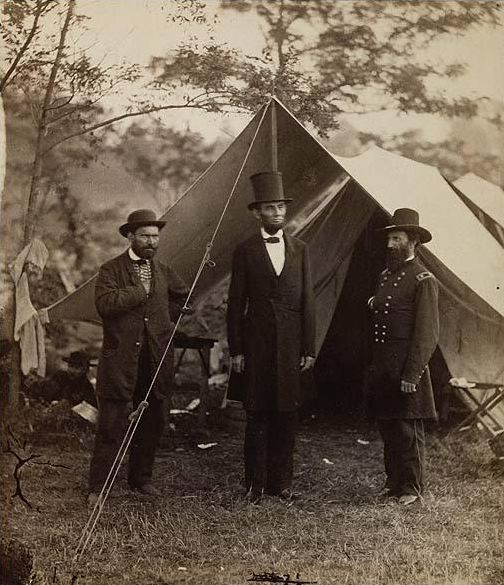

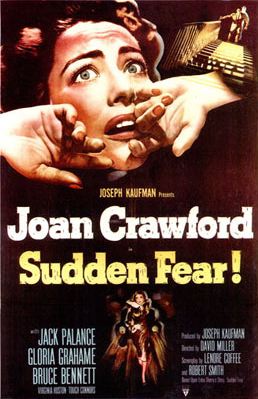

When the situation is looked at from the woman's point of view, we leave the territory of noir

— move into another tradition, typically that of the psychological

suspense thriller, of the Hitchcockian variety, which is often

presented from the viewpoint of the female, with whom we

identify. This tradition predated noir and is in fact connected to works of Victorian Gothic fiction, such as Jane Eyre.

It deals with more traditional female anxieties arising out of the

contradictions of an insecure patriarchy. To me it makes no sense

to call this sort of movie film noir, even though it may tap into the same mood of existential dread that pervades the classic noir.

As I've observed before, it took the neo-noir Chinatown to look back on the noir

tradition and try to imagine the effect of its male insecurities on

women — but this was never really a conscious concern of classic film noir.