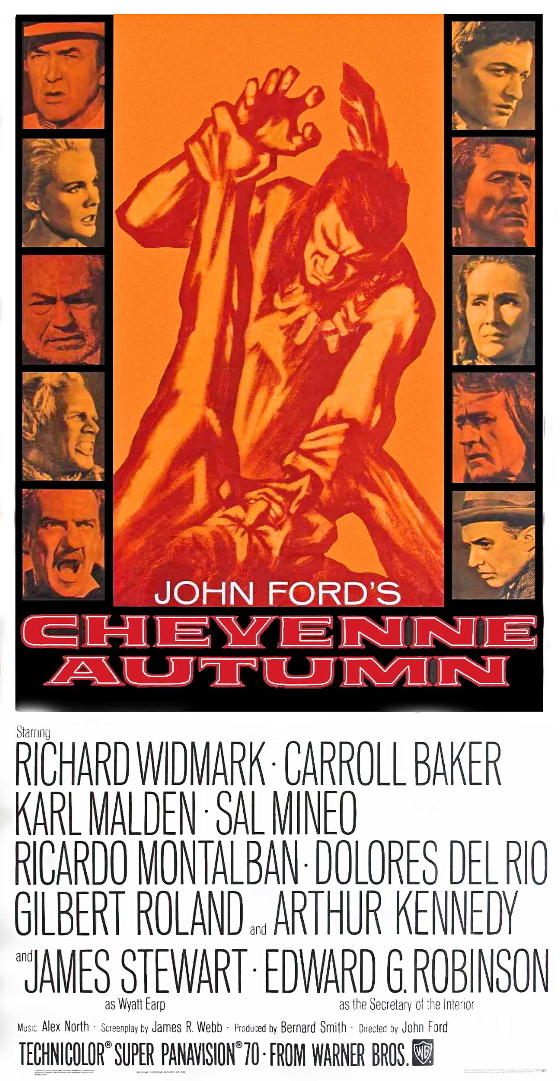

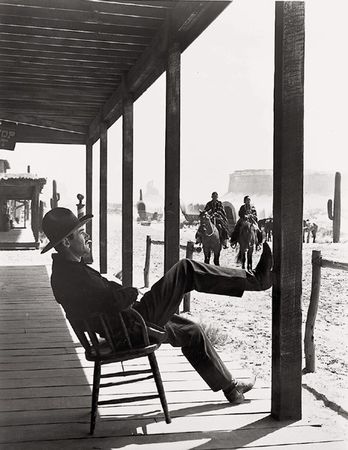

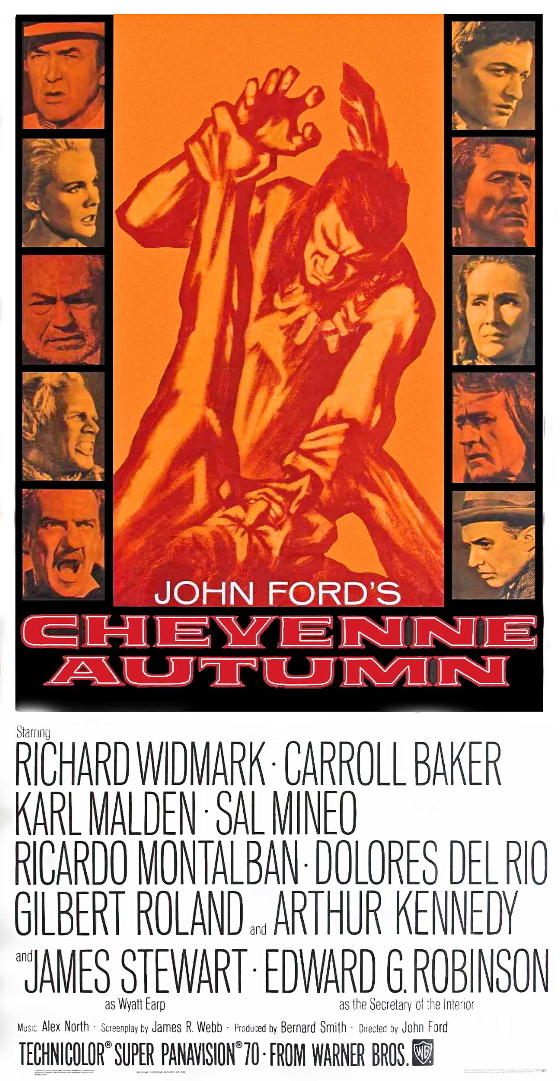

This

was the next to last feature film John Ford completed, in 1964, when he

was 69 years-old. It doesn't work as a drama, much less a

melodrama, or as a character study or as an historical epic . . . but

it's one of the most sublime visual poems in the history of movies and

a very great work of art.

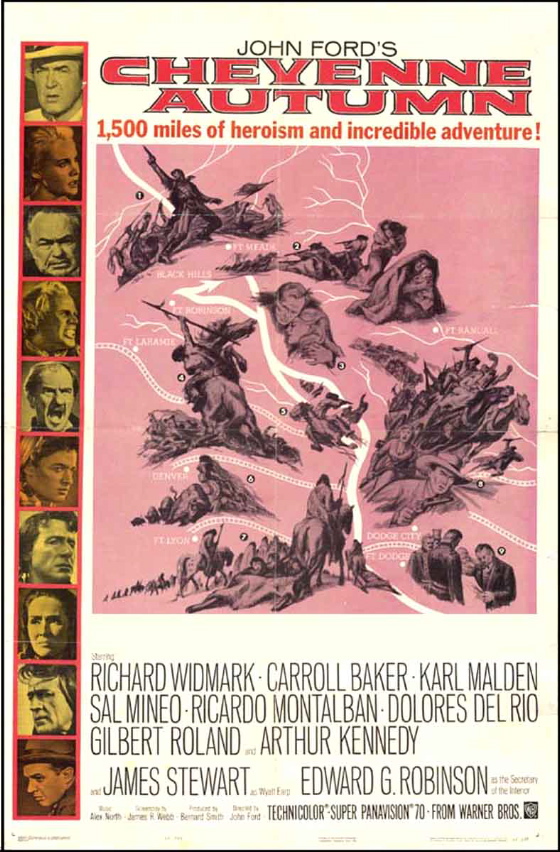

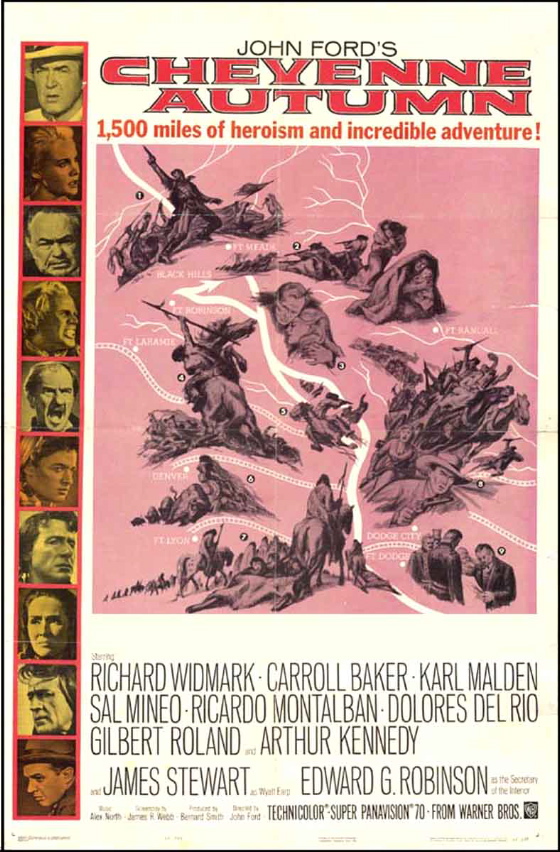

It tells the once little-known story of a band of Cheyenne who, in

1879, broke out of confinement on a reservation in Indian territory,

present-day Oklahoma, and made a 1500-mile trek back to their homeland

in Montana. Pursued and harried by a succession of cavalry

expeditions, starved and near death, the band made it to its old home where

it was allowed to remain.

In his excellent commentary on the wonderful new DVD edition of the film, Ford

biographer Joseph McBride says that Ford originally intended to make Cheyenne Autumn

as a small, black-and-white film, an intimate study of the Cheyenne

pilgrims, but that he was persuaded by the studio to expand it into a

big wide-screen Technicolor extravaganza. It was, says McBride, a

“Faustian bargain” which led to a film that was neither fish nor fowl,

since Ford lost sight of the Cheyenne characters yet failed to create a

genuine epic.

This may indeed reflect the development of the project but I think it

misses the essence of the film that Ford finally made. All

of the characters in the film, both Cheyenne and white, recede into the

images, become secondary to the images. Ford doesn't lose sight

of them as dramatic personae because he has no real interest in them as

dramatic personae. They're just narrative markers that guide us

through the landscape of the film.

Landscape was always a character in

Ford's Westerns, a kind of Greek chorus commenting on the relative

smallness of human intention and desire. It stood in, one might

even say, for the regard of Eternity, in which human endeavor held an

insignificant place. It transformed the melodrama of his stories

into tragic

absurdity.

In Cheyenne Autumn, as in

Shakespeare's late romances, the author lost interest in the mechanics

of plot altogether, in the centrality of individual character, and became enchanted by the

mystery of his medium — the magical poetry of words, in Shakespeare's

case, and of images in Ford's. The

progress of the Cheyenne through the magnificence of the landscape, the

evolutions of mounted cavalry on the march or at the charge, fill

Ford's imagination fully — the characters dissolve into the beauty of

movement itself. They are elevated into a transcendent glory not

by the specificity of self but by their possession of space. They

are dancers, sculptures in motion.

This is not an abstract vision, however, a celebration of

technique. In his old age, disillusioned with the legends of the

West he did so much to reinforce, Ford lost his faith in man's

essential goodness, or at least in that part of it related to his

will. Primal values, transcending individual human character,

were all he could believe in — the dumb urge to go home, to preserve

community, to do one's duty.

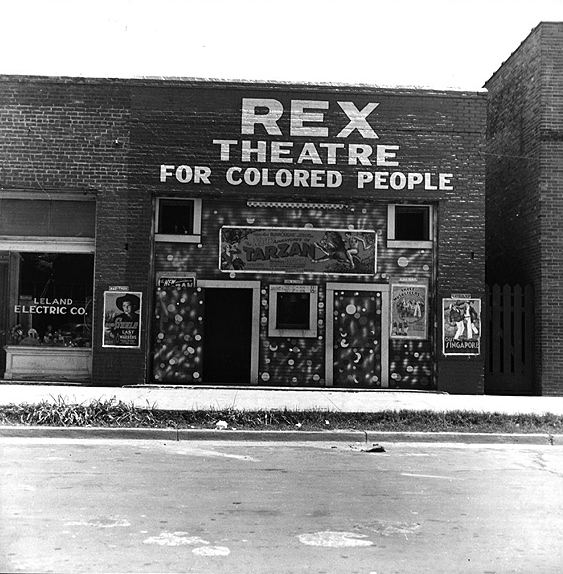

At the center of the film Ford inserted, unaccountably to many critics,

a 21-minute sequence set in Dodge City which mercilessly satirizes the

myth of the Western hero, of the frontier town. Jimmy Stewart

appears as a corrupt and cynical Wyatt Earp leading the hysterical townspeople on an

absurd pursuit of the phantom Cheyenne, who in truth are nowhere near

Dodge. The familiar narrative of the old West is deconstructed, revealed as

a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

After this strange interlude, the film switches back to the story of

the Cheyenne, doing what they have to do, and the horse soldiers, doing

what they have to do. When the Cheyenne are restored to their

ancestral Eden, Ford shows us how much they have lost recovering it,

just as

he shows us how much honor the soldiers have lost in fulfilling a duty

that's been applied to a meaningless and inhuman mission.

The triumph on both sides was only in the journey, the movement, the dream — all of

which vanish in the end, as the eternal landscape looks on impassively.

The

film has a nominal “upbeat” resolution in its penultimate episode in

which

Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, wonderfully played by Edward G.

Robinson, goes to visit the escaped Cheyenne in Montana and promises to

help them stay there. This scene, oddly, is shot against

cheesy-looking back-projections — such a radical violation of the look

of the rest of the film that it almost seems deliberately surreal . . .

as though Ford was asking us not to take this superficial “climax” too

seriously. Perhaps it can be compared to the improbable events

that “resolve” the narrative of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale,

in which the playwright seems to be asking us to laugh with him at the

conventions of the stage — to remind us that the true heart of his

work lies elsewhere.