With the notable exception of Stagecoach,

I'm not a big fan of the movies John Ford made with screenwriter Dudley

Nichols, even though these include some of Ford's most celebrated and

entertaining films.

Nichols was an extremely skillful writer, with a sound sense of story structure and a good ear (usually) for

colorful dialogue. But he also had a self-conscious, “literary”

style — he tended to see situations and characters in emblematic,

metaphorical terms. This aspect of Nichols' work encouraged Ford

to indulge his gorgeous visual expressionism at the expense of what he

did best — create cinematic spaces and places of mesmerizing

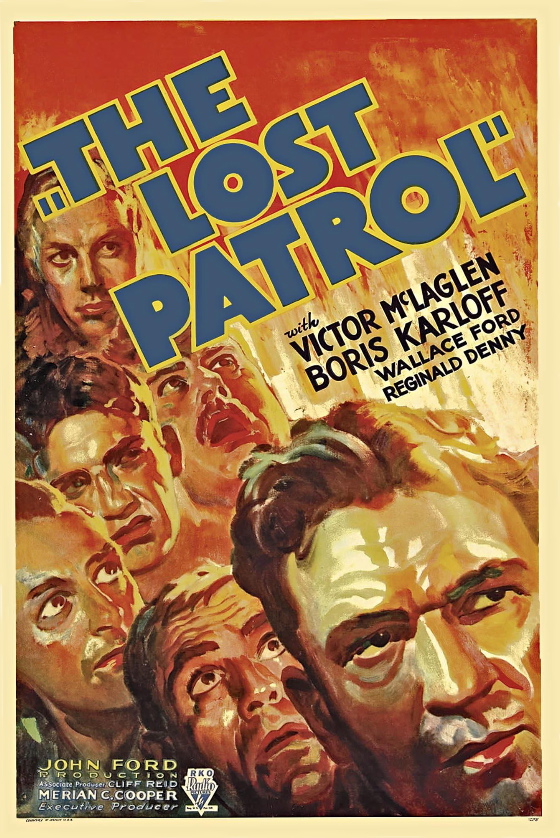

specificity. The images of The Lost Patrol and The Informer

are supremely beautiful but they grow claustrophobic after a

while. The desert and the fog-bound city are too obviously

surrogates for existential states, symbolic and airless.

In his best work Ford found ways of imbuing interiors and landscapes

with an uninsistent symbolic quality — we read them as real spaces and

feel their emotional resonances on a subliminal level. We have a

sense of discovering and exploring these spaces on our own, no matter

how many times we come back to them. The shadowy streets of Gypo

Nolan's Dublin in The Informer, the merciless desert that swallows up The Lost Patrol, are places we visit with a guide, always reminding us what these environments “mean”.

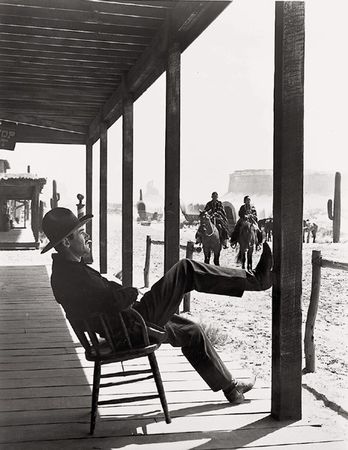

The streets of Tombstone in My Darling Clementine,

the unfinished church on the edge of town, the maze of the O. K.

Corral, are every bit as charged with meaning and significance, but

Ford lets us tease them out for ourselves — he lets us inhabit them at

our ease, until the places seem to speak to us in their own voices.