One

of the enduring myths of Hollywood is that the town is an eternal

battleground between art and commerce — between studio executives who

only care about money and filmmakers who only care about art.

The truth is that movies have been, almost since the moment they were

invented, a popular art form. They attracted, for the most part,

popular artists — which is to say, artists who wanted to reach large

audiences. Long before there was an established studio system run

by corporate functionaries, filmmakers courted a mass audience and

reached it. The financial returns that followed created the industry that corporations at once set about dominating and controlling.

The art of cinema was created by the same people who created the mass

market for films — Griffith, Chaplin, Pickford, Keaton, Lloyd.

Because they were popular artists, commerce was an intimate aspect of

their endeavor. The corporate executives who took over the

industry these artists created were by no means more

interested in the box office than the artists had been — they were

interested in power and turning the art form into a more predictable

revenue source . . . interests which often conflicted with maximum

box-office potential.

When executives and filmmakers clashed over the content of films, it

was not a battle between art and commerce — it was a battle between

popular artists who actually knew how to make popular films and

bean-counters who thought they knew better. Since the

bean-counters quickly gained a virtual monopoly over the distribution

of films, they had the last word, and also the ability to insure that

this word could never be challenged, since the overruled filmmakers had

no practical way of getting films before the public without the

bean-counters' consent.

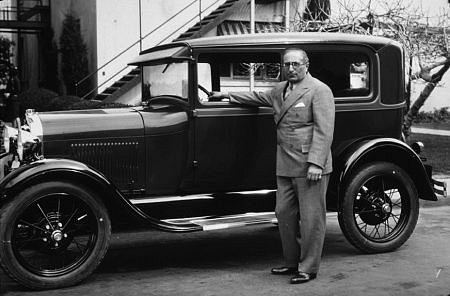

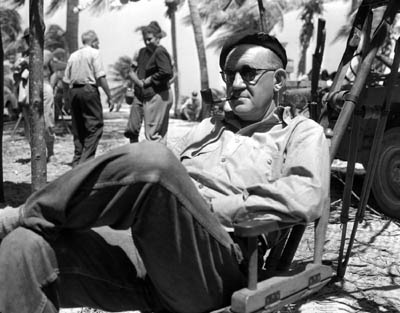

John Ford fought constantly with studio executives and, by his account,

never won a single battle with them — but does anyone seriously

believe that Ford, one of the most consistently successful popular

artists since Dickens, was fighting for some private, noncommercial artistic vision? Ford did make a few films, like The Fugitive,

which he may have known in advance would not be wildly commercial, but

for the most part he wanted to address a mass audience as effectively

as possible. For a genuine popular artist like Ford — or Dickens, or Shakespeare, for that matter — there is no

conflict between art and commerce.

Ford was fighting against executives who could not have created a

popular work of art if their lives depended on it, executives who only

managed and bullied and second-guessed those who could create such

works. The real issue was not art or commerce — it was

power. Without their corporate control of the means of film

distribution, these executives would have remained in the realm of

exhibition, from which most of them emerged and where they belonged.

Hollywood in truth has been a battleground between monopoly and a free

market, between corporate standardization and homogenization and

entrepreneurial innovation. The conflict between art and commerce

has been nothing more than a smokescreen.