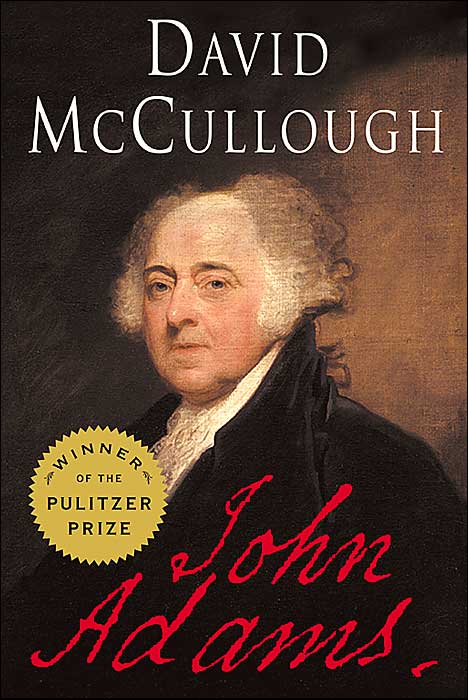

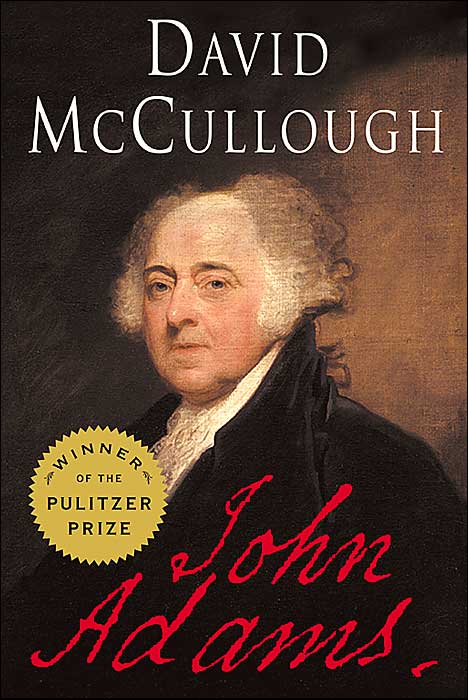

I commend to all my fellow citizens of this republic David McCullough's wonderful biography John Adams.

(That's Adams, bald and slightly pot-bellied, standing in the exact

center of John Trumbull's painting of the signing of the Declaration Of

Independence, above.) Erudite and sagacious the book is also

compulsively readable, magically evoking the physical world of the 18th

and early 19th Centuries but also bringing the men of the Revolutionary

era to vivid life.

The founders of the United States Of America were certainly the

God-damnedest collection of characters who ever collaborated on a great

enterprise. They seem mysteriously modern, perhaps because they

remain so recognizably American

— frank, down-to-earth, open-minded, industrious, optimistic . . . also pig-headed, venal and hypocritical

There were scoundrels and rakes among them, men of faith and skeptics,

simple farmers and grand seigneurs — but they were all so unaccountably radical in their devotion to the ideas (if not always to the practical realities) of liberty and equality, of self-government.

And they were brave. All the men above seen signing the

Declaration, many of them men of great wealth and position, would have

been hung as traitors by the English if their improbable revolution had

failed. They don't seem to have had the slightest doubt that it

was a risk worth taking, and merely joked about the jeopardy — as

Franklin did when he said, “We must hang together or hang separately.”

It can't really be explained, except as a result of something that had

evolved over many generations in the experience of living in the new

world, habits of self-reliance and independence which the Founding

Fathers explicated and guided but did not invent. Adams himself

knew this. “The Revolution,” he wrote, “was in the minds and

hearts of the people.”

Adams may have been the oddest of all the “indispensable men” of that

time — neither a soldier nor a politician of any particular skill, not

a great writer or thinker but possessed of an orderly mind and endless

energy, he had a personal independence of thought and an an

incorruptible integrity which made him the go-to guy in any crisis.

It was Adams who ensured the appointment of George Washington as

commander in chief of the Continental Army, Adams who procured loans

from the Dutch to keep the government afloat in the early days of the

Confederation, Adams who, in drafting the Constitution of the

Commonwealth Of Massachusetts, created a key model for the American

Constitution.

And it was Adams who served as America's first ambassador to the Court of St. James, received with honor as the representative of a new and independent nation by the same king who had once hoped to hang him.

The whole tale is surreal, unbelievable, but one loves Adams because he

didn't see it that way. He seems always to have believed that the

seeds of liberty, once planted in good soil, would bear fruit — just

as the seeds he sowed on his Massachusetts farm brought forth peas and

corn. At the end he was proud of what he had done for his

country, but he was just as proud of his farm.

Adams became President of course, for one term, after serving as George

Washington's Vice-President for two terms. He lost his bid for

reelection to his then arch-rival Thomas Jefferson, and became the

first President to hand over the reigns of power unwillingly, convinced

that Jefferson would ruin the new nation before it could fairly get

going. He groused about it, then jumped into a public stagecoach

and rode home, back to his farm, his peas and his corn. He bowed

to the will of the people without further complaint.

In that moment, the American experiment justified itself to itself and to the whole world.

Perhaps the strangest thing about looking at these old

revolutionaries today is that they always seem to be staring right back at us, at the American future we

now inhabit. In their regard there's hardly more than a trace of

self-satisfaction in what they accomplised, not a lot of sentiment, and

more than a little impatience. “We started this business well enough,” they seem to

be saying, “now get on with it.”

[I read the biography as a prelude to watching HBO's upcoming

mini-series taken from it, starring Paul Giamatti as Adams. This

strikes me as a brilliant piece of casting, Giamatti having a knack for

conveying the kind of adorable peevishness which many people observed

as a characteristic trait of Adams. The series will premiere on March 16.]