In 1942, right after he finished principal photography on his second film, The Magnificent Ambersons,

but before editing on it began, Orson Welles headed off to make a film

in Brazil promoting inter-American friendship. America was at war

and Welles had been convinced by the government that it was his

patriotic duty to undertake this assignment, designed to keep our

neighbors to the south from drifting into the sphere of Axis influence.

Welles, exempted from military service by various ailments, could

hardly have refused. He planned to make an omnibus film mixing

fictional and documentary episodes

— a kind of essay on aspects of South American culture. He fell

in love with Brazil and groped his way slowly towards a form in which

to convey what he found there, finally settling on the history of the

samba as a key to the society.

His groping frustrated his corporate masters at RKO back in

Hollywood. They were also worried that much of his documentary

footage of Carnival and the samba clubs of Rio showed what they called

“jigaboos” mixing and dancing with white people. It was precisely

this racial diversity that Welles admired in the Brazilian culture.

Eventually RKO pulled the plug on the project. Welles was left

with one camera, no sound equipment, 40,000 feet of black-and-white

film and $10,000. Hoping to salvage something from the adventure,

he headed north to what was then the small coastal village of Fortaleza (below) to make a documentary-like reconstruction of a

legendary event in recent Brazilian history — the 1500-mile voyage of

four fisherman on a crude sailing raft to present grievances to the

government in Rio.

The voyage made the four men national heroes, and they were received by

Brazil's strongman leader, a sort of populist dictator, who granted the

substance of their demands.

Welles shot most of the footage he needed for this film-within-a-film,

but was never allowed to edit it. After his death, the footage

was assembled into something presentable and included in a documentary

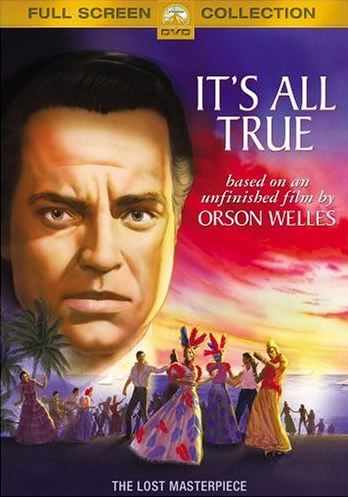

about Welles' ill-fated Brazilian project. The documentary is now

available on DVD:

The episode of the four fishermen, even crudely reconstructed, is

simply stunning. It may be the most beautiful semi-documentary

ever made. Eisenstein's very similar project, done in Mexico a

decade earlier, ¡Que Viva Mexico!, looks like static fashion photography by comparison. Four Men On A Raft, as Welles called the episode, also blows away the semi-documentaries of Robert Flaherty (like Nanook Of the North) and Michael Powell (The Edge Of the World.)

Welles's images are dynamic, lyrical, full of movement and yet also

convey a convincing documentary feel. They are cinematic poetry

of the highest order.

Simon Callow, in his multi-volume biography of Welles, says that if

Welles had shot nothing else in his life but this footage he would have

to be recognized as one of the supreme masters of cinema. This is

true.

While Welles was creating this miracle in Brazil, the executives at

RKO, with the aid of some of Welles' most trusted associates, were busy

mutilating The Magnificent Ambersons.

They blamed the collapse of the South American film on Welles's

procrastination and extravagance, even though he had not exceeded the

project's budget at the time it was scrapped. The vandalism of Ambersons

had a vindictive quality to it, to judge by internal RKO correspondence

on the subject, and the myth of Welles as an irresponsible artist,

created by RKO to justify its actions, which included the dismantling

of Welles' production unit at RKO, haunted him for the rest of his life.

RKO made a point of destroying the footage they cut from Ambersons, although Hollywood figures like David O. Selznick begged them to preserve it, but the It's All True footage somehow survived. It includes ravishing Technicolor sequences shot in Rio, some of which can be seen in the It's All True documentary . . . and the material for Four Men On A Raft. (The color images above are not from the film.)

Do

yourself a favor sometime and have a look at the material on the DVD —

unfinished as it is, it's still one of the treasures of 20th-Century

art.

Tks Lloyd. You make this aspect of Welles' legacy so intriguing.

I came across this article by Lawrence Russell, which explores a similar vein, and has some interesting background on this “lost” project: http://www.culturecourt.com/F/Hollywood/AllTrue.htm

Thanks for the link — very interesting.

There's a book by Catherine Benamou based on massive research into the project but apparently written in impenetrable academic jargon. Still might be worth checking out.

All the footage Welles shot exists but hasn't been preserved — including 100,000 feet that has never even been printed. Let's hope it gets saved before the nitrate decomposes!