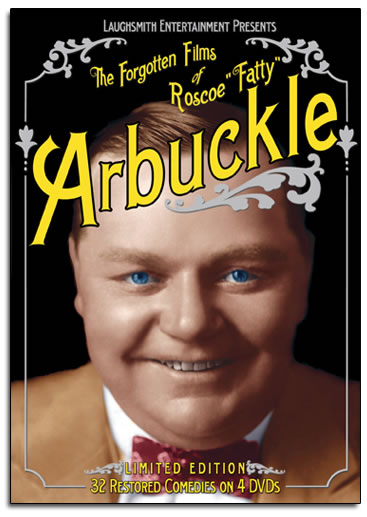

In 1920, Roscoe Arbuckle became the first great comedian of the silent screen to make a full-on transition from shorts to feature films. Chaplin had appeared in the feature comedy Tillie’s Punctured Romance as early as 1914, but under Mack Sennett’s direction and as a second lead. Chaplin wouldn’t release his own first feature until 1921. Buster Keaton starred in The Saphead in 1920 but he continued to make shorts after that until 1923, when his feature career began in earnest with Three Ages.

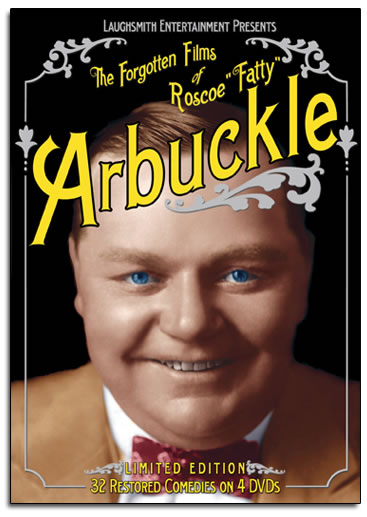

Arbuckle made nine feature films in the two years before scandal interrupted

his career, and never appeared in another. I believe that all but three

of them are lost, and the last two were never released in America, due

to the scandal. One of these, Leap Year, survives and is included on

the magnificent DVD set The Forgotten Films Of Fatty Arbuckle. It’s

absolutely fascinating.

In the earlier shorts offered in the collection we can see Arbuckle

transition slowly from the comic actor of the Sennett farces to the

full-blown silent clown of the Comiques. Chaplin and Keaton seemed to

have intuited almost from the moment they stepped in front of a camera

that the silent cinema was perfectly adapted to a fixed clown persona

— a character who could migrate from film to film yet still stay

essentially the same, with a way of moving, of being in space, that,

along with a few clothing props, singled him out as a distinct,

slightly hyper-real being, much like a circus clown or a figure from

the Commedia dell’ Arte.

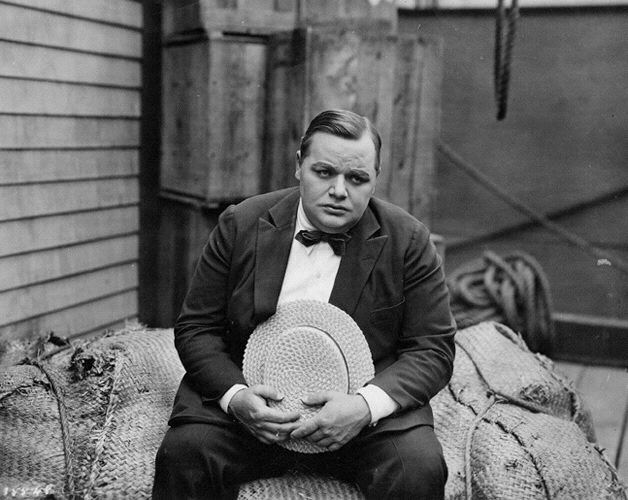

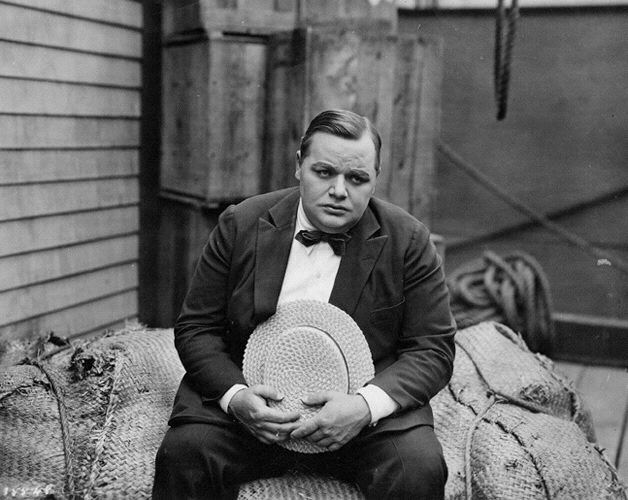

Roscoe moved slowly from being a comic actor who did funny physical bits to

incarnating “Fatty”, the slapstick clown, and all along the journey he

was pulled back to the former mode. In the films he did with Mabel

Normand, character, especially as embodied in their relationship, took

precedence over slapstick — at least until the trademark Sennett

mayhem of the climax. In one of the Sennett films Roscoe directed, He

Did and He Didn’t, he takes this mode even further, edging into the

realm of upper-class drawing-room comedy, with very sophisticated

lighting and photography.

Until I saw Leap Year I would have seen this mode as a detour in Arbuckle’s

development as a comedian — a detour on the road to the Comiques,

where Arbuckle takes his place with Keaton and Chaplin as a classic

slapstick clown. Leap Year, though, totally altered my sense of what

Arbuckle was about. It’s as far from the universe of the Comiques as

it’s possible to get.

It inhabits, in fact, the universe of P. G. Wodehouse, whose gentle,

kindly satires of the young and well-heeled beautiful people of his

time were immensely popular in 1920. Leap Year perfectly captures the

sweetly daft world of Wodehouse’s slightly nutty, vaguely dimwitted but

immensely lovable trust-fund kids of the jazz age.

The miracle of it is that Arbuckle, knockabout comedian extraordinaire,

funny slapstick fat guy, fits so perfectly into this world. He does it

by simply behaving as though he’s Cary Grant in a romantic comedy, Fred

Astaire in a romantic musical — and because he doesn’t doubt it for a

moment, neither do we.

Roscoe plays the feckless nephew of a rich man, presumably the heir to a vast

fortune. This could explain part of the reason he’s so irresistible to

the women in the film — but not all of it. He’s a genuinely romantic

leading man. His sweetness and his physical grace sell us on that. He

just dances through the role.

The film doesn’t allow for much slapstick, but Arbuckle finds ways of

slipping it in delightfully here and there — most notably in a scene in which he’s

trying to convince his would-be brides that he’s having fits. The fits

are little masterpieces of physical comedy, as fine as anything Chaplin

and Keaton were capable of at their best.

But the performance doesn’t depend on these things, and the film remains a

frothy drawing-room farce. The farce becomes strained at times,

particularly towards the end, and the froth congeals a bit, but the

overall effect is of lightness and joy. It reminded me a little of

Murnau’s The Finances Of the Archduke from 1924 — particularly in

its use of the sunny Catalina settings of the film’s middle section, in

which the landscape seems to conspire in the fun, as the Dalmatian

coast did in Murnau’s film..

Was this really the sort of film that the mad surreal clown of the Comiques

wanted to make? He certainly seems to be fully committed to the work

and having a hell of a good time. Were the other Arbuckle features

anything like this? If Arbuckle’s career had continued on its natural

course, and he’d taken greater command over his films as a director —

where on earth would he have ended up?

This film expanded my appreciation of Arbuckle’s range and genius and

altered my sense of the comic landscape of films in 1920. It’s easy to

think of Arbuckle as an actor whose journey towards becoming another

Chaplin, another Keaton, was tragically diverted. But maybe he would

have become something else entirely — something we can’t even imagine,

because he wasn’t able to show it to us.