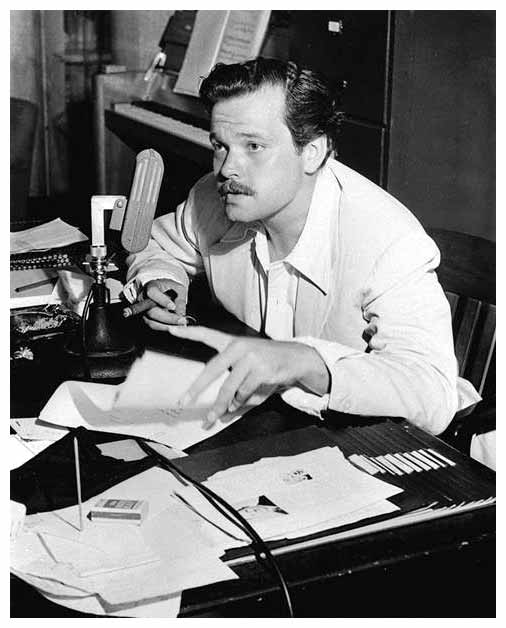

Recently I've been listening to a lot of radio drama, which had an amazing run on the public airwaves for almost thirty years, between the 1930s and the 1950s. Attempts to revive it almost always fail, because radio dramatists have forgotten Orson Welles's great insight into the form — that it's primarily a narrative rather than a dramatic medium.

The reason for this is simple, I think — the imaginative world of radio is obscure and threatening, like a labyrinth that has to be negotiated in the dark. We don't want to go there without a guide, without the voice of a storyteller to lead us on. This can be an omniscient narrator, or a character in the tale recounting it to us, orienting us, letting us know that we won't be abandoned in the course of our journey.

Modern radio playwrights think we have what it takes to pick up all the clues we need from dialogue or sound effects, to piece together the narrative the way we do in live theater or in movies, from the dramatic elements of the story, but we don't — because radio storytelling reduces us to a state of childlike dependency, takes us back to the time when an oil lamp or a blazing hearth fought off the immense darkness of the nighttime world.

In that charmed circle of flickering, transient light, the storyteller offered himself as an authority on the dark regions of the mind which night invoked, he provided a path through them and an assurance of return. Without that authority, radio tales are bleak and alienating, abstract puzzles to be solved . . . just so much noise outside the window, while we inhabit a state of mind which doesn't want to think about what's going on outside the window, in the endless realm of darkness.