My friends Tracy and John had a baby today. His name is Maxwell.

Welcome to the world, kid.

My friends Tracy and John had a baby today. His name is Maxwell.

Welcome to the world, kid.

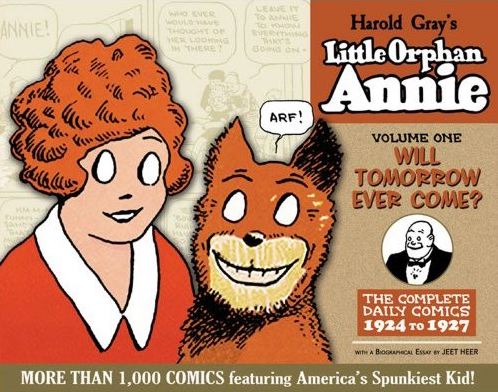

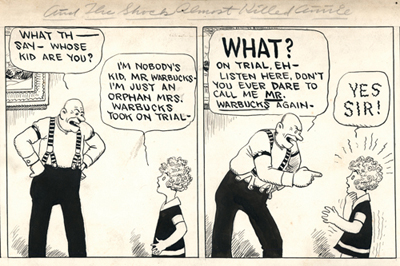

Things just keep getting better and better for fans of classic American comic strips. Little Orphan Annie has just been added to the list of strips that are being reprinted in volumes that will eventually cover the entire runs of these comics.

The first volume is available now. It includes the first few years of the strip, beautifully reproduced, mostly from Harold Gray's original drawings or from the syndication proofs. In them, the plucky Annie knocks about America spreading kindness or kicking ass, as the situation requires.

Here's a philosophical question for you. Why was it that American popular culture, back in the darkest days of patriarchy, kept coming up with images of powerful little girls, like Annie and Dorothy of Kansas, who set off on their own on dangerous journeys and triumphed over all adversities by force of character . . . while in our own nominally feminist age the most prominent role models for young girls are sexually objectified teen tartlets?

There are now four volumes out of the early Dick Tracy strips, seven or eight of Krazy Kat, three of Gasoline Alley and Terry and the Pirates, two books which contain complete runs of Winsor McCay's Little Sammy Sneeze and Dreams Of the Rarebit Fiend — plus two huge volumes which reprint color Sunday pages from Gasoline Alley and Little Nemo In Slumberland. If you pile them all up beside your bed or easy chair and read a few strips or pages a day, you've got your own personal funny pages to hand, some compensation for the fact that modern newspapers have no space for popular art this brilliant and this entertaining.

There's been such an uproar, such expressions of shock, over the possibility that a group of girls at a high school in Gloucester, Massachusetts may have entered into a pact to get pregnant and help each other raise their babies. It strikes me as a perfectly reasonable proposition, given the world these young women are living in. They obviously have no expectation of finding young men willing to be committed husbands and fathers, so they are doing what female elephants do — they are organizing for a matriarchal social order.

In the social order of elephants, young males are forced out of the herd as soon as they attain sexual maturity. The males wander about singly or in small groups, getting into all sorts of trouble, fighting with each other and destroying things, and are let back into the herd only long enough to mate with sexually mature females — at which point they are forcibly ejected once again. The young are raised exclusively by females. It's a kind of pregnancy pact.

Male elephants have not made the case to female elephants that they could be useful for something other than impregnating them, and female elephants have responded in the only logical way possible — they have taken responsibility for organizing their society along lines that ensure both stability and the perpetuation of the species.

Given the state of American manhood these days, why should American women — at least those more interested in motherhood than in careers — behave any differently? Check out the iconography of the ad for Juno at the head of this post — it's very easy to read. Men are clueless dorks, it says — women rule. Juno stands before an orange evocation of the American flag like George C. Scott at the beginning of Patton. The guy doesn't seem to know where he is or what he's doing there. He could vanish and it would make no difference to Juno whatsoever.

If there was a pregnancy pact in Gloucester it may just mark the beginning of a massive earthshaking female elephant stampede. Young American men may have to prepare themselves for a lifetime of wandering around aimlessly, rubbing the bark off of trees for no good reason at all.

This legendary film has a set-up that promises a rattling good yarn —

two lifelong friends pitted against each other in mortal combat by a

callow but irresistible woman. It is directed in bravura style, with

flashes of cinematic brilliance, by a master of film narrative,

Clarence Brown, and it features two of the silent screen's most

appealing actors, Greta Garbo and John Gilbert. The result is

watchable, even entertaining — but deeply unsatisfying on almost every

level.

We see in this film what the 20th-Century, and the studio system in

Hollywood, did to the melodrama — perverting it meretriciously,

heartlessly, systematically, fatally.

The melodrama of the Victorian stage, of Griffith and Pickford and even

Murnau, was a stylized form in which a glamorized virtue was beset by

crude though recognizable obstacles which seemed invincible but which

virtue could vanquish, though often only by self-sacrifice and in death.

We may laugh at the form today, or find it charmingly quaint, but it

represented a sophisticated dramatic tradition capable of conveying

deep emotion and serious moral reflection. It is hardly more laughable

or quaint than modern forms, in which a superior display of aptitude

with firearms can right any wrong, in which glamor or cuteness alone

can resolve any romantic complication, in which material or

professional success signals the triumph of the good.

Melodrama only becomes grotesque and artificial when those who make it

lose faith, consciously or unconsciously, in virtue, especially in

self-sacrificial virtue. In our self-obsessed age, at least before 11

September 2001, virtue became suspect — a sucker's game — and sacrifice

unthinkable. Not being able to have it all seemed a crime against a

basic entitlement of humanity — or at least that part of it lucky

enough to be born into Western middle-class comfort.

This is why modern intellectual sophisticates laughed at the melodrama

of Titanic, though its moral complexity far exceeded the dime-store

nihilism, or self-referential fantasy, delivered by the hip filmmakers

of the 90's. It was taken seriously, however, by ordinary people — and

especially by teenage women, who knew on some level that the nihilism

and fantasy of their parents' generation had come to a dead end, had

not prepared them for the world they saw before them, the world of

Columbine and Osama bin Laden.

Flesh and the Devil represents a first step in the destruction of

melodrama as a viable form — as Titanic may represent a first step

in its rehabilitation. In Flesh and the Devil, virtue is dessicated

— evil lush and ripe. Though the story tells us again and again that

Barbara Kent is the good girl and Greta Garbo the bad girl, every

single act of craft and genius on display in the film struggles to

persuade us otherwise.

We are far from Griffith and Pickford here, whose great heroines showed

us how appealing, energetic, sexy and even seductive virtue could be.

Greta Garbo becomes, in essence, the auteur of Flesh and the Devil,

because all its narrative ploys, all its moral stances, collapse into

worship of her mysterious presence, her oddly luminous flesh.

In strictly narrative terms, there has rarely been a more extreme

example of misogyny on film. Garbo's character is unremittingly evil —

her heartlessness, until the last unconvincing moments of the role, is

absolute, her greed and selfishness both repellent and unmitigated. But

Brown's camera and Brown's casting and Brown's staging worship at her

feet. All the other characters are perfunctorily drawn, wooden in

presentation, with two exceptions. One is the kindly old priest who is

roused to an almost sexual excitement by his hatred of the Garbo

character — a hatred which the narrative invites us to share. The

other is Gilbert . . . who struggles manfully to discover a complexity,

a moral gravity in his character. In his final scenes he almost

succeeds, but the odds are against him, the game was rigged from the

start. The film believes in nothing but Garbo — virtue has no defense

against her, can reassert itself only by killing her.

One thinks of what the film could have been if those who made it were

aware of this — had some sense of the moral questions it raises. If

Garbo's character had been granted a soul, instead of stripped of it,

if Barbara Kent's character had been given even a hint of Gish's or

Pickford's complexity and will and sensuality, the delicious

possibilities of the tale could have unfolded into real melodrama —

which is to say, real drama.

But this film is an early demonstration of the use of a star to avoid

drama, to avoid moral questions, to parade unfelt clichés and

undeveloped characters and irresponsible attitudes before an audience

mesmerized by glamor alone. A melodrama in which virtue has evaporated

is not melodrama anymore — it's more like Grand Guignol, without the

shameless energy, the giddy frissons, the amoral abandon of a real

Theater of Blood.

I'm not sure we can blame Garbo's collaborators too harshly for this,

though — she is sui generis. There is really no word for what she does

on screen. It's not acting, it's not even performing — she is simply a

creature who has her being on film . . . the camera devours her, every

molecule of her. The process leaves nothing behind — no memory of a

character, or even of a human being caught on film. She paradoxically

incarnates the gossamer moods of certain kinds of passion, certain

kinds of physical enchantment — and vanishes as mysteriously as they

do. But it's useless to deny how spectacular the phenomenon is, how

strange and pleasurable — just as it's useless to deny the charm of

falling in love.

Brown and his cameraman and his screenwriters and his actors may have

to be forgiven for losing their heads in her presence, and even for

hating her power to undo them so utterly.

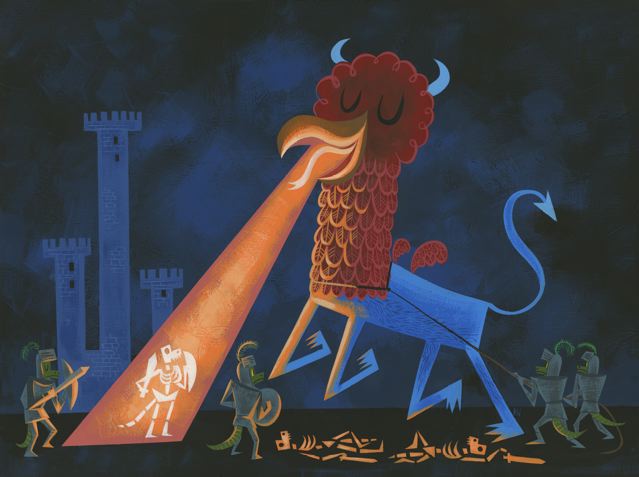

The image above, Griffin Lava Breath, is from a new show by Amanda Visell opening today at the M Modern Gallery in Palm Springs, California. The show is called Tic Toc Apocalypse and features images of horror done in a cheerful cartoon-modern style. What fun!

Click here for a preview of the show.

I've had many strange experiences in Las Vegas, but none stranger that seeing David Irving speak in a small banquet room at the Jokers Wild Casino, a little locals' joint on Boulder Highway, at the edge of town.

Irving is a very controversial historian of the Third Reich whom I've written about before, here and here. The most prodigious researcher in the German archives pertaining to National Socialism, and in the archives of the Allies that house captured German documents on the subject, Irving has written a series of books which are essential compendia of facts about Hitler and his state. But he has a bias — a desire to show that Hitler and the Nazis weren't as bad as everybody thinks, and that the Allied leaders were far worse than anybody thinks.

His motives in this are suspect, since he occasionally reveals anti-Semitic attitudes that offend the conscience, but his facts are always right, even if he marshals them to serve a twisted argument. His books are respected, with reservations, by respectable historians, but he has been vilified mercilessly by just about everybody else.

He was imprisoned for over a year, in solitary confinement, in Austria for giving a speech in which he noted that the gas chambers at the Auschwitz historical site are reconstructions, which is true, and arguing that gassing was not in fact used systematically to kill prisoners there, which is hotly contested by other historians and by eyewitnesses. His words were thought to violate Austrian laws against Holocaust denial.

Irving is not exactly a Holocaust denier — more of a Holocaust minimizer. He admits that many bad things were done to Jews by the Nazis, just not as many bad things as historians have claimed. And he insists that Hitler was out of the loop as far as the Final Solution was concerned — that Himmler instituted mass killings on his own hook, so that the “Messiah” of the German Reich would not be tainted by the policy.

This strains credulity, of course — imagining that a faithful lieutenant would do something so momentous on his own, something which Hitler would be held accountable for even if he knew nothing about it. Still, Irving can point to the fact that no document recording Hitler's acquiescence in the mass extermination of Jews survives, and that Himmler regularly removed allusions to the policy from reports he passed on to the Führer.

It strikes me as more likely that Himmler simply had an understanding with Hitler that the policy of extermination would not be referenced in high-level documents of any kind, so that Hitler would never have to contend with opposition to it from his high-placed generals and ministers, and that Himmler would take the fall for it politically if it ever became generally known. It wouldn't be the first time a politician used plausible deniability to try and cover his ass.

It's equally possible that documents recording Hitler's involvement in the Final Solution were destroyed before or during the apocalypse of Germany's collapse.

When I showed up at the Jokers Wild Casino I almost bumped into Irving as he wheeled a cart with boxes of his books into the place. I greeted him but he hurried on gruffly, perhaps embarrassed by being seen in shorts and a sports-shirt hauling his own merchandise.

His talk was held after a buffet dinner, included in the price of the lecture, in a small private room off the casino's coffee shop. The food was school cafeteria quality and barely warm. There were about eleven other people in attendance. I kept to myself, fearing what sort of conversations my fellow attendees might initiate. I overheard one older guy railing against democracy — “It allows people to let off steam, to think they have some say over their government. America isn't a government, anyway . . . it's a corporation.”

Irving's talk was generally reasonable. He spoke at length about his imprisonment, and the tale was genuinely harrowing. Irving reported to the outside world that the library of his prison contained several books he had written. At this point, a high Austrian official ordered all books by Irving in all Austrian prisons to be removed and burned — “To show the world that we have moved beyond the Nazi era.” The minister seemed to see no irony in using a book burning to demonstrate this point.

Irving then talked about his forthcoming biography of Himmler, which he promised would put to rest once and for all the idea that Hitler knew about the Holocaust. He said he expected to endure further persecution upon its publication.

Irving said a few troubling things. He said he told the Austrian press when he was finally released from prison that “Mel Gibson was right.” He didn't elaborate on this in Austria, but to us he explained, “You know, about who started all the world's wars.” In other words, the Jews. He said that Churchill did not become anti-Nazi until after he was paid 48 thousand pounds by a Jewish organization in 1936 — an amount, Irving said, worth about 3 million dollars in today's currency. The implication was that all of Churchill's fine rhetoric was bought and paid for by Jews.

An odd evening with an odd man in an odd place in an odd town. That's Vegas, baby.

American show business has always had a strong element of surrealism. One can read American show business as the arena in which Americans have attempted to come to terms with the dislocations and paradoxes of the American experiment itself. American culture owed a debt to but also wanted to break free of European culture. It has always tried to reconcile Puritanism with a penchant for frontier license. Although initially Anglo-centric, it welcomed a wide variety of other cultures and tried to incorporate them into the American sensibility.

The crucial dialogue of American culture has been conducted between its European and its African roots. Official separation of our white and black populations, undermined by a practical proximity and integration, led to a complex and profound conversation, conducted in code, which in many ways has defined American culture. The minstrel tradition, spirituals, blues, jazz, swing and rock were the result of a musical intercourse that has always remained problematic on a conscious level, deeply engaging on a spiritual and emotional level — not just because it raised the issue of unsettled social questions, but because it exemplified the very essence of our national character.

The essence of our national character is that it doesn't know itself, that it has no core — that it consists of one long negotiation between heterogeneous elements that resist synthesis. That is, of course, what makes American culture so alive and dynamic and fertile — its improvisatory nature, its fundamental instability, which is also a fundamental openness to anything. Liberty, in a political sense, would have no “legs”, would close on Saturday night, if it weren't reflected in this liberty of the everyday imagination — and this liberty of the imagination could probably not have survived if we were required to take it too seriously, to think it through . . . if it weren't dressed up in shameless, unadulterated hokum.

So Louis Armstrong, one of the two or three greatest artists of the 20th Century, who happened to be black, had to appear in public rolling his eyes comically, with a minstrel-show smile.

So Elvis Presley could celebrate black musical culture in the Neverland of rock and roll — as long as he presented the public face of a nice, buttoned-up Southern white boy when he wasn't performing.

The madness of it all is breathtaking, but it's madness with a method. Hokum is what leads us by the back door into the heart of the American dream.

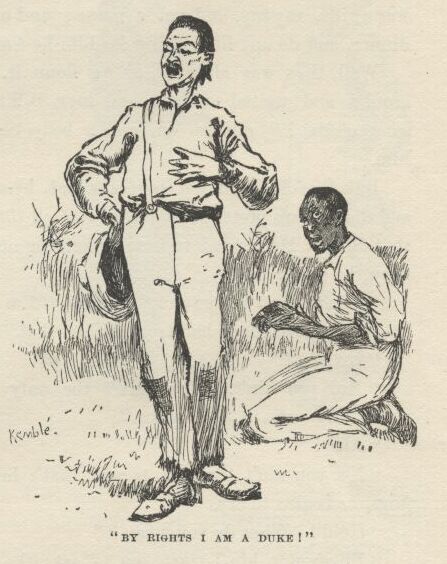

The Duke and the Dauphin in Huckleberry Finn are

a paradigm of all American show business. Claiming a bogus descent

from European royalty, these two rogues peddle their preposterous spectacle (a little misremembered Shakespeare here, a little gross-out humor there) from

town to town, from meeting hall to meeting hall. They don't quite

deliver what they promise, and sometimes get run out of town for their unfulfilled claims — but, hey, that's entertainment, too. Who could ever

forget them? Clearly the Royal Nonesuch will become part of the legend of any town they play, just as it has become part of the mythology of American literature.

They incarnate the spirit of the minstrel show, the circus, vaudeville, the Hollywood musical and American Idol. They are the patron saints of sublime American hokum — one part hooey, one part bunkum, seasoned with chutzpah and a dash of sheer genius — and even when we're tarring and feathering them, we love them . . . because they are us and, on some level, the best of us.

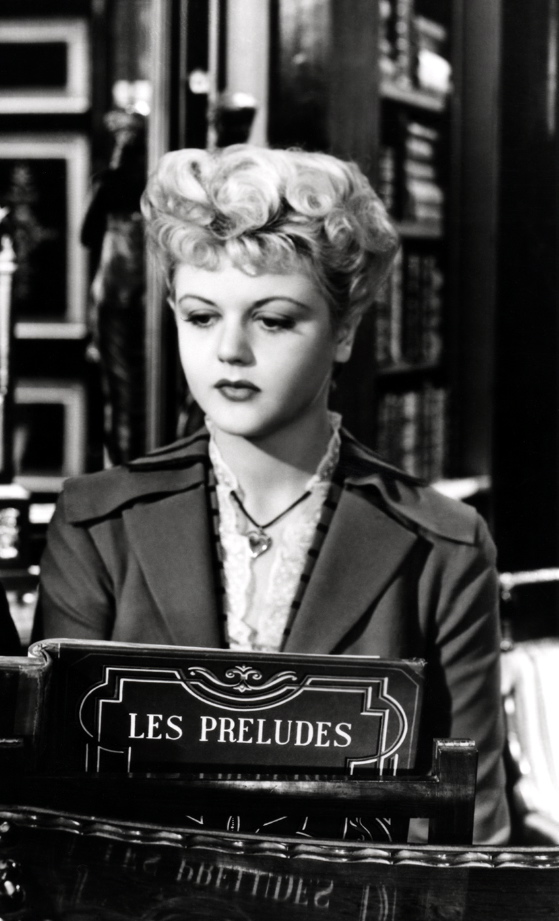

. . . to think about CNN anchor Brianna Keilar. She's really cute. She reminds me of the young Angela Lansbury, who was also really cute:

Brianna is a golf fanatic.

When she was in college — not that long ago — she wrote an interesting paper about John Ford's Rio Grande. (The things you can stumble across on the Internet!)

My friend Cotty writes to recommend the film The Edge Of Heaven and to record his disappointment at the small size of the audience he saw it with. He concludes:

Strange times in the movie business. Five independent distributors have disappeared or been absorbed or are under severe threat, all within the last sixty days. Warner Independent, Picturehouse, New Line, Vantage, and ThinkFilm all going or gone. Who will make and distribute movies that rely on audiences caring to leave the house just for the sake of the experience of the emotional connection that only movies can bring?

Despite complaints from disappointed or estranged film-makers, the fault, I think, lies not in our stars, or their managers or their studio enablers, but in ourselves. If we don't go, why should they build it?

Perhaps the Obama candidacy can revive a sense of connection, can remind us of a common experience of America's great strength in diversity, her powerful e pluribus unum past and the blunt necessity of shared response to global problems. But it will come too late to help Strand Releasing [distributor of The Edge Of Heaven] in its attempt to bring you a lovely and cinematic time in the darkened common room that is a movie theater.

Good thoughts for these bad movie times, but I'm inclined to play the Devil's advocate and argue that the public is never wrong — that if good people shun good films, then there's something wrong with the films, at least as works of popular art. Films can be good and still not be works of popular art, but why are there so few good popular films?

The example of Obama's candidacy does, I think, point to the answer. Four years ago the American public rejected, by a slim margin, John Kerry, who would (I think we can all now say in hindsight) have been a better President than George Bush . . . but he wasn't the sort of President most Americans wanted. His candidacy reeked of Democratic Party caution and calculation, his case to the public was cast in Senatorial, which is to say, conventional Washington, rhetoric. He was a new version of the same old thing, so why not stick with the familiar version of the same old thing already installed in the White House?

If John Kerry and George Bush really are the same old thing, fundamentally, why not choose the guy you'd rather have a beer with? If the latest art-house release and the latest action-hero extravaganza are just variations on outdated paradigms, why not go see the one with the loudest explosions, the one everybody at school is going to be talking about next week?

One can come up with rational arguments against these propositions — like the war in Iraq, for example, or the mind-numbing boredom of too much CGI — but culture, political and artistic, is not a purely rational thing. It's too easy to convince yourself that George Bush might have known what he was doing when he invaded Iraq, or that the next Spiderman film is going to kick ass.

When politics and/or popular art don't reach something higher in us than business as usual, than commodity merchandising, we tend to rebel and refuse to make sensible distinctions between good and bad products. We often act against our own best interests out of a kind of unconscious rage . . . because we don't want politics or popular art to be about “products” at all, or not only about products.

I think this explains why Republicans have been able to persuade lower-income Americans to vote Republican against their own economic interests by pushing “values” buttons — by suggesting that gay marriage, for example, is an assault on “the traditional family”. It's irrational, but to such Americans even an irrational vote in favor of “the traditional family” makes more sense than pretending that one corporate-sponsored political product is better than another.

On the left, the phenomenon would explain all the votes for Ralph Nader in 2000, which may well have cost Al Gore the Presidency. More importantly, it explains the millions in the last two elections who voted with their rear-ends by planting them firmly on their couches and staying away from the polls altogether. Again, it seems irrational, contrary to self-interest, but in fact reflects, at least on one level, a perfectly rational disgust with the whole system.

This year the Democratic Party machine, with its support for Hillary Clinton, tried to offer Americans an even newer version of the same old political product — a female political product! — and came very close to putting it over on us.

Obama beat her not because he had a more effective mask covering his political product-ness — a black political product! — but because his whole campaign, everything about him, felt genuinely different. He spoke in a new kind of language which we've hardly ever heard from Washington, he raised money from small-time donors which made him independent of the Democratic Party machine, he sent out an army of organizers who didn't look or act or talk like party hacks.

And yet . . . he spoke to old values, to popular concerns, to the shared e pluribus unum past Cotty mentions, one that is still with us, still capable of inspiring us.

The lesson in this for me, as it relates to movies, is that the mass of people don't really want anything that has the stink of current movie logic on it — neither wonderful little art-house movies nor committee-made would-be blockbusters. They'll settle for them, if they can't get anything better, but in smaller and smaller numbers and with less and less enthusiasm.

They want something that feels different on a molecular level, the way Obama's campaign feels different on a molecular level. They want a change, a fundamental change — even though that change, like Obama's rhetoric, may take us back to old, forgotten truths.

Movies, like Obama, don't have to choose between an isolated integrity and pandering to the tastes of the masses — they can choose another path . . . honoring the tastes of the masses, as Obama has honored the aspirations of a broad public. The key is believing that the aspirations of the broad public are worth honoring, and trusting the broad public to respond. It requires a leap of faith, a violation of all conventional wisdom, a wild kind of hope. It requires, in short, something as improbable as Barack Obama's candidacy.

So my question to filmmakers is, as one Obama bumper sticker puts it — Got hope?

THE FILM

The genius of Hollywood in its Golden Age was in glamorizing simple virtue — the most famous case in point being Casablanca, which managed to make the sacrifice of true love for a higher cause seem unspeakably cool.

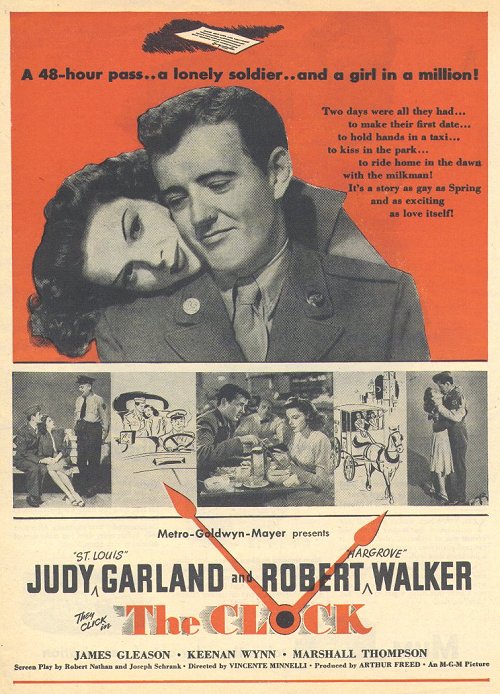

Another film made during and about WWII is in some ways even more impressive and certainly more moving. In Vincente Minnelli's The Clock Judy Garland plays a Manhattan secretary who meets a serviceman, played by Robert Walker, on 48-hour leave in the city before heading overseas.

What “heading overseas” suggested when the film was made (1944) has to be kept in mind while watching The Clock today, because it's crucial to every moment of the film, which takes the full measure of what it means to fall in love in the face of mortal peril. In some ways the gravity of the lovers' predicament in this tale is what allows Minnelli to pull off the miracle at the heart of it — giving the story of two totally ordinary people the grandeur of the most sublime romance from legend or myth.

James Agee wrote a beautiful appreciation of the film when it came out, which can be found in his collected criticism, Agee On Film, and can't be improved upon, but check out this interesting view from a contemporary blog, The Sheila Variations. It's worth pointing out, too, that this was the first non-musical film directed by Minnelli and produced by Arthur Freed, who had the previous year collaborated on one of the greatest movies ever made in Hollywood, Meet Me In St. Louis, a musical also starring Judy Garland.

Garland and Minnelli were in love during the making of these films, and Minnelli's feeling for the actress informs every frame of them — she is a radiant being in these movies, glamorized, certainly, but in a down-to-earth way that suggests the way ordinary people glamorize a new love. Minnelli seemed to find everything about her enchanting, which is why he could present her in such simple roles without feeling a need to “sell” her charms in any way, to make her larger than life. For him, clearly, she was already larger than life, even when she walked across a room or ate some soup.

Garland doesn't behave like a star in The Clock — she doesn't need to. The state of being loved relieves her of the need to appeal to any outside authority for approval. The result is paradoxical. She grows as an actor, becomes more fascinating as a screen presence, even as she retires into herself, makes us comes to her.

Like James Cameron's Titanic, The Clock manages to convey the narrative of a life-long love in a very compressed period of time — the awareness of death in both stories allows us, as it forces the characters, to read immense import into the simplest gestures, the most modest acts of sympathy and kindness, the plainest impulses of physical attraction.

In The Clock, as in the beginning of any real love affair, less is more. The way Garland adjusts Walker's tie at the train station before saying goodbye to him tells us more about the wedding night they've just shared than any dramatization of it could have suggested. Its very discreetness evokes the privacy of genuine intimacy, and yet we share it, not as voyeurs but as privileged participants in its magic.

As Garland leaves Walker's train the camera follows her and then rises up inexorably, in one long, tracking crane shot, until she's lost in the crowd at the station — her story, which is our story, too, now, becomes one story among many, and no less extraordinary for that.

THE VISUAL STYLE

Although the tracking crane shot described above is one of the most beautiful and effective single images in all of cinema, The Clock is not a consistently interesting film visually. Set in New York but shot almost entirely on the back lot of MGM in Culver City, it relies very heavily on backscreen projections, which cumulatively produce a claustrophobic effect. This doesn't hurt the story too badly, since part of Minnelli's strategy in telling it is to focus our attention closely on the growing intimacy between Garland and Walker, which he charts with great delicacy. The body language of two strangers falling in love has rarely been evoked with such precision and sympathy. It's a “visual effect” which, more often than not, trumps cinematic style.

The sound-stage recreation of the train station is spectacular, consistent with its crucial role in the drama, as is the recreation of the subway stations where the lead characters lose each other, in a brilliantly shot and choreographed passage.

Citizen Kane, made just a few years earlier, contains this same mixture of spatially seductive choreography on sets and relatively alienating process photography. In Kane, the mixture is weighted towards the former, in The Clock towards the latter, though Minnelli demonstrates his mastery by reserving the “set” pieces for passages where he really needs them — where a visceral appreciation of the space the characters inhabit is crucial to the emotional effect of the scenes.

But there are moments when the process photography undercuts the emotional effect — as in the scene where Walker runs after Garland on the bus. It's a cute gag played against process screens — it would have been heart-stopping played on a practical set or a real location.

THE CONTEXT

“Glamorizing virtue” was part of the commercial calculation of Hollywood, especially at MGM, where studio boss Louis B. Mayer insisted that MGM films promote “family values”. These were values that Mayer touted but did not practice. In middle age he dumped his aging spouse for a more glamorous trophy wife. He treated his stars like farm animals — pampered farm animals, admittedly, ones he expected to win him blue ribbons at the county fair.

Mayer copped feels from the teen-aged Garland at every opportunity, even though he wasn't especially attracted to her — he was just exercising the greengrocer's prerogative to squeeze the produce. MGM plied Garland with amphetamines when her work load slowed her down, then “graciously” paid for her rehab when she crashed, hoping they could still get some more mileage out of her.

This sort of hypocrisy is visible in many of the sentimental films made at MGM — like the wildly popular Andy Hardy series, made for peanuts and consistently profitable for almost a decade. Mayer loved these films, but seen today they reek of calculation and exploitation. All their sentiment seems not only contrived but downright cynical. The films do have their moments — the homespun virtues they celebrate are intrinsically attractive — and if you're in the right mood they can get to you. More often you're keenly aware of being manipulated by shrewd hacks.

Arthur Freed, who produced The Clock, and most of MGM's great musicals, was hardly a saint, and is reported to have had recourse to the casting couch at MGM on occasion, but he was devoted to his family throughout his life, and he imbued everything he worked on with genuine feeling — contrived, certainly, engineered with old-fashioned theatrical calculation, but never cynical, even for a moment. His films could be corny, way too obvious and even clumsy in their appeal to the heart, but you never get a sense that the artists who made them are trying to put something over on you they don't believe in themselves.

Freed's sincerity is what elevated films like The Clock and Meet Me In St. Louis above the sort of saccharine platitudes found in the Andy Hardy series. One can say for Mayer that he recognized the real thing when he saw it and backed Freed to the hilt as a producer, even when the other great minds on the lot dismissed Freed's stories as simple-minded. Freed rewarded Mayer's faith with sublime works of art which also made money — with films which now constitute the core of Mayer's legacy. Without Freed, that legacy would consist mostly of clever junk like Love Finds Andy Hardy, which plays today like a mediocre, padded-out sitcom.

It

took some pushing and shoving and tough talk from her backers in

Congress, but Hillary Clinton finally acknowledged that Barack Obama

had won the Democratic nomination for President. Then she endorsed

him, plausibly and honorably in a speech that spoke to the historic

nature of both their candidacies. I think one can say that nothing in

her campaign became her like the leaving it. (Image above © Zina Saunders, with thanks to Potrzebie.)

Obama also got a different kind of endorsement from a different kind of icon. In a recent interview Bob Dylan said:

Well,

you know right now America is in a state of upheaval. Poverty is demoralising. You can't expect people to have the virtue of

purity when they are poor. But we've got this guy out there now who is

redefining the nature of politics from the ground up…Barack Obama.

He's redefining what a politician is, so we'll have to see how things

play out. Am I hopeful? Yes, I'm hopeful that things might change. Some

things are going to have to. You

should always take the best from the past, leave the worst back there

and go forward into the future.

From the very tail end of this (with thanks to Cotty.)

As you probably know, Barack Obama will give his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention on

the anniversary of the March On Washington and Martin Luther King's “I Have A Dream”

speech, in 1963. As you may also know, Bob Dylan was there. Check it out here:

Awesome times, then and now.

From the New York web log four years ago:

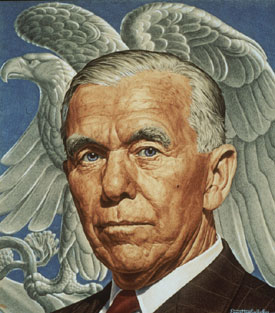

On 12 February 1944, George Marshall, Chief Of Staff of the U. S. Armed Forces, sent the following order to Dwight Eisenhower:

“You will enter the continent of Europe and, in conjunction with the other United Nations, undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.”

There were other parts to the order, mostly concerned with Eisenhower's chain of command, but the above represents the only formal operational directive he was ever given — essentially “invade Europe and win the war.” Marshall's disinclination to micro-manage Eisenhower's campaign resulted from no lack of capacity or ambition on his part. He had hoped that when the time came FDR would give him operational command of the invasion of Europe — which would be the greatest combined operation, the greatest amphibious assault in the history of warfare. In fact, FDR did offer the command to Marshall but said that he would prefer having Marshall at his side in Washington for the war's duration. Marshall chose to honor that preference, which more or less explains why Eisenhower became President and is well known today, while Marshall did not and is not.

Eisenhower's campaign in Europe may well be remembered as the most consequential feat of arms in the history of our civilization, second only perhaps to the holding action fought at Thermopylae by 300 Spartans and assorted allies under the command of Leonidas in 480 B. C. The Spartans had decided to sacrifice themselves in a hopeless stand against the invading Persian forces, which may have numbered a quarter of a million men, as an example to the squabbling city states of Greece, to inspire them to unite to drive out Xerxes and his apparently invincible hordes. It worked.

If Persia had destroyed Greek civilization and its proto-democracies, if Hitler had been able to establish and maintain dominion over Europe, the world would be a far darker place today than it already is.

Before the battle at Thermopylae, the Spartans, who knew full well that they were all going to die, asked for a memorial to be erected over their graves with these words carved on it — “Go tell the Spartans that we lie dead here, in obedience to our laws.” The G. I.s who lie dead beneath the pristine white crosses of the cemetery above Omaha Beach did not ask for any such memorial to be erected or any such message to be sent. If they had, it would probably have been something just as simple — “Tell the folks back home that we got the job done.”

At the time, the message was clear enough. When Anne Frank, still in hiding in Amsterdam, heard the news about D-Day she wrote in her diary, “This is it! The invasion has begun! I might be able to go back to school in September.” Before that could happen she was discovered and taken off to a concentration camp, where she suffered a wretched death from typhus , but a lot of teenage boys not much older than she was died to give her that moment of wild hope, precious almost beyond imagining.

2:50 pm, 6 June 2004, NYC

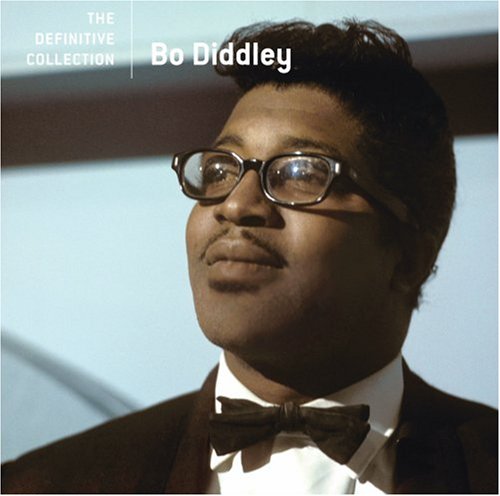

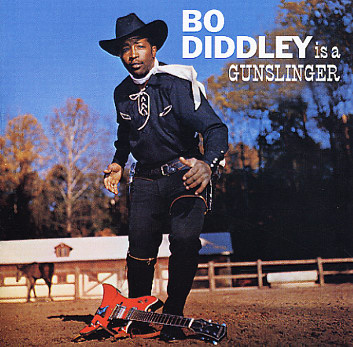

You thought you were in bad shape. You thought you couldn't go on. Then the angels sent Bo Diddley to remind you of an eternal truth — as long as you can move your hips, life is good.

The angels have taken Bo Diddley home, but his message endures. Listen to some Bo Diddley today.

Surf's up . . . or not. Who cares?

By Al Moore, for Esquire. (With thanks to ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Archive.)