American show business has always had a strong element of surrealism. One can read American show business as the arena in which Americans have attempted to come to terms with the dislocations and paradoxes of the American experiment itself. American culture owed a debt to but also wanted to break free of European culture. It has always tried to reconcile Puritanism with a penchant for frontier license. Although initially Anglo-centric, it welcomed a wide variety of other cultures and tried to incorporate them into the American sensibility.

The crucial dialogue of American culture has been conducted between its European and its African roots. Official separation of our white and black populations, undermined by a practical proximity and integration, led to a complex and profound conversation, conducted in code, which in many ways has defined American culture. The minstrel tradition, spirituals, blues, jazz, swing and rock were the result of a musical intercourse that has always remained problematic on a conscious level, deeply engaging on a spiritual and emotional level — not just because it raised the issue of unsettled social questions, but because it exemplified the very essence of our national character.

The essence of our national character is that it doesn't know itself, that it has no core — that it consists of one long negotiation between heterogeneous elements that resist synthesis. That is, of course, what makes American culture so alive and dynamic and fertile — its improvisatory nature, its fundamental instability, which is also a fundamental openness to anything. Liberty, in a political sense, would have no “legs”, would close on Saturday night, if it weren't reflected in this liberty of the everyday imagination — and this liberty of the imagination could probably not have survived if we were required to take it too seriously, to think it through . . . if it weren't dressed up in shameless, unadulterated hokum.

So Louis Armstrong, one of the two or three greatest artists of the 20th Century, who happened to be black, had to appear in public rolling his eyes comically, with a minstrel-show smile.

So Elvis Presley could celebrate black musical culture in the Neverland of rock and roll — as long as he presented the public face of a nice, buttoned-up Southern white boy when he wasn't performing.

The madness of it all is breathtaking, but it's madness with a method. Hokum is what leads us by the back door into the heart of the American dream.

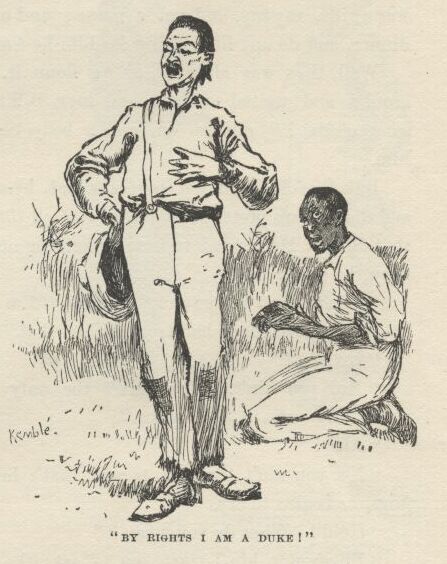

The Duke and the Dauphin in Huckleberry Finn are

a paradigm of all American show business. Claiming a bogus descent

from European royalty, these two rogues peddle their preposterous spectacle (a little misremembered Shakespeare here, a little gross-out humor there) from

town to town, from meeting hall to meeting hall. They don't quite

deliver what they promise, and sometimes get run out of town for their unfulfilled claims — but, hey, that's entertainment, too. Who could ever

forget them? Clearly the Royal Nonesuch will become part of the legend of any town they play, just as it has become part of the mythology of American literature.

They incarnate the spirit of the minstrel show, the circus, vaudeville, the Hollywood musical and American Idol. They are the patron saints of sublime American hokum — one part hooey, one part bunkum, seasoned with chutzpah and a dash of sheer genius — and even when we're tarring and feathering them, we love them . . . because they are us and, on some level, the best of us.

Hi Lloyd. A very interesting and eloquent post.

But I have some qualms:

1. Elvis was always upfront about the black roots of his music and never denied the influence of blues-men such as Arthur 'Big Boy' Cruddup, who penned Elvis' first sun release, That's Alright Mama.

2. Louie Armstrong's tragic facade is not something to be celebrated. This was brought home to me a few years back in an Asian hotel night-club, where a black singer from the US was accepting requests. I stupidly asked for 'It's a Wonderful World', and the guy with unbridled hostility refused and told me it's not a wonderful world…

3. Spike Lee in his Bamboozled (2000) does not share you benign view of the minstrel show. I can understand his anger.

You're right about Elvis on a personal level — he always acknowledged the black roots of his music and seems to have been without prejudice of any kind. But the public persona engineered for him by the Colonel emphasized a kind of Wonder-Bread quality — mainstream and white.

The minstrel tradition is complex and is undergoing a lot of rethinking these days. It had its hateful side, which should never be forgotten, but it had subterranean functions which could be positive. It was, in fact, created by blacks, and functioned with a kind of irony which contained a critique of the “mask of blackness” built into it.

I certainly would never “celebrate” it — it revealed a deep pathology in American society — but it had humane impulses as well. Armstrong's “mask of blackness” was a tragic necessity, but Armstrong influenced American culture more profoundly than any other artist of the 20th Century. He was an “Uncle Tom” who called the tune for everybody.

Which fact about Armstrong is “truer”, more important? It seems to me that both have to be taken into account — and that in some way both are in Armstrong's music.