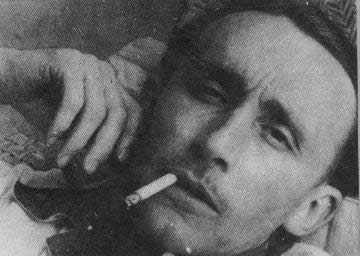

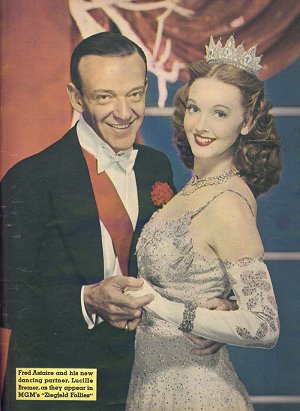

She gained movie immortality in her first film, playing Rose Smith, Judy Garland's older sister, in Meet Me In St. Louis. The next year she danced with Fred Astaire in Yolanda and the Thief, and when that film proved to be a flop, her career took a precipitous downward turn.

She danced with Astaire again in the movie musical revue Ziegfeld Follies, adorned the cover of Life magazine in 1946 and had a supporting role in Till the Clouds Roll By the same year, but MGM gave up on her after that, loaning her out to poverty-row studios for parts in negligible films.

She threw in the towel soon afterward, married the son of a former President of Mexico and went to live with him in La Paz, Baja California, until their divorce in 1963.

Bremer had been a Rockette and a Broadway chorus girl before moving to Los Angeles. She was spotted by Arthur Freed dancing in a show at the Versailles nightclub, given a screen test and almost immediately cast in Meet Me In St. Louis, which Freed produced. She is often referred to as a “protégée” of Freed, and one of Judy Garland's biographers says she was sleeping with him, which might account for her meteoric rise at MGM. I hate to think of her sleeping with Freed, a married man, while they were making Meet Me In St. Louis, that heartfelt paean to family values, but Hollywood is Hollywood.

I don't know what accounted for her meteoric fall. She was a good actress and a talented dancer, but I wouldn't say she had star quality, and in Till the Clouds Roll By she sometimes looks haggard, worn out at 29. Of course Garland was burnt out at an even younger age — MGM had that effect on some people.

It's a strange and sad tale, except for the part about La Paz, one of my favorite places on earth. I like to think of Rose Smith strolling along the malecón there, of an evening, enjoying the breeze off the Mar de Cortes, far from the intrigues of Culver City.

[Image above © 2007 Harry Rossi]