It's almost impossible to understand the culture we live in without knowing the Bible, simply because the culture we live in was created by people for whom the Bible was a central text, a central reference point. I'm speaking of the Bible as a literary document, a compendium of phrases, images, folk wisdom and psychological insight — all of which it is, quite apart from its specifically religious nature.

This was brought home to me recently listening to the commentary on the recent DVD release by Criterion of Max Ophüls's The Earrings Of Madame de . . . . It's delivered by two female academics who chatter on at great length about the sexual politics of the film, referencing Freud and Stendhal promiscuously but missing the film's central reference to a passage in the Gospels.

[Warning — plot spoilers ahead . . .]

The commentators disagree about whether or not Louise, the film's main character, consummates her adulterous affair with Count Donati. This despite the fact that, while praying to the Blessed Virgin in private, she says she was unfaithful “only in thought”. “And what is a thought?” she asks the Virgin. One commentator suggests that Louise, an inveterate liar, is here lying to the Mother Of God. This is, in itself, quite preposterous. Why would anyone pray to a saint who couldn't see through a human lie?

Both commentators miss the real import of the question — its reference to Jesus's teaching in Matthew's gospel . . . “Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shalt not commit adultery: But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart.”

It is precisely this reference which goes to the heart of the film's themes.

Louise's husband in the film commits adultery in the flesh, but in a discreet way that does not disturb the civil compromise of their marriage. He loves his wife and tolerates her flirtations, because he believes that, while she might not love him, she loves no one else. For him, this isn't much of a bargain, but it is the bargain on which his whole life depends, as we eventually see.

He might have tolerated a discreet adulterous affair on her part, as long as it was frivolous. When she falls in love with someone else, he is destroyed. He cannot tolerate her committing adultery in her heart.

Seen from this perspective it's impossible to read the husband's violent and destructive actions as exercises in patriarchal authority — they are, in fact, exercises in existential despair. It is also impossible to read Louise's actions as exercises in pure passion, pure self-realization, because they also involve extreme cruelty towards her husband. Perhaps she doesn't know what she means to him, but we cannot help feeling that she should know — that not knowing, or caring, involves a deep moral failure . . . deeper than any casual extramarital affair would represent.

At the beginning of the film, as Louise is searching through her possessions for something to sell to raise some quick cash, she comes across a prayer book, or an edition of the New Testament, with a cross on its cover. “I need you now,” she says to the book — meaning, I need your help raising the cash. Seen retrospectively, in light of her last question to the Virgin, the need she expresses in this first scene has a profound ironic implication. What she really has needed all along was an appreciation of what it means to commit adultery in one's heart — an appreciation of its extreme seriousness.

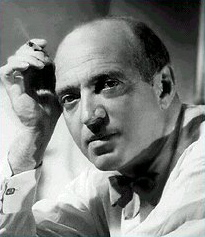

Louise's question is not asked at the end of the novel on which Ophüls's film was based — there is no scene in the book corresponding to the one in the film in which Louise donates her fatal earrings to the Virgin. This was Ophüls's invention — and it's the key to the story he was telling. For Ophüls (above), a Jew, there was probably no religious dimension to the Christian text he was referencing, but there was certainly a reference to the psychological truth at the heart of Jesus's words. It is, as I say, a vital element of the film unavailable to anyone unfamiliar with those words.

Ophüls was a highly educated and cultured man. In 1954 he would have assumed that any educated and cultured viewer of The Earrings of Madame de . . . would register the allusion to the gospel text, and note the irony of a vain and self-centered woman like Louise being clueless about it, even as she prays to her saint for the things she wants in life. 54 years on, we cannot assume that even a college professor will have a clue about it.