Do not open until 25 December!

Monthly Archives: December 2008

IN THE CHRISTMAS SPIRIT

Over at the Hard Rock Casino the cocktail waitresses have started wearing their cute little Christmas costumes, very similar to the outfit worn above by Stephanie Sadorra, Las Vegas model and poker player, who was spotted recently at the Hard Rock poker room.

One of the female dealers in the room also wears a similar costume, with fingernails painted green for an extra festive touch, but she says the outfit is uncomfortable because it's made of polyester and doesn't breathe.

Men rarely appreciate what women go though in order to achieve cuteness.

THE END OF ENGLIGH

Dr. Drew Casper is the Alfred and Alma Hitchcock Professor Of American Film at the University of Southern California. He is a published author on film. I assume that the “Dr.” in front of his name means that he has a PhD. Casper shows up often delivering “expert commentary” on DVDs. I assume that he speaks English as a first language but somehow in his journey through academia he has not managed to master the rudiments of his native tongue.

His style of speaking involves a lot of rephrasing, designed, I suppose, to suggest the addition of nuance to the points he's making but adding up only to redundancy. In his commentary on the recent DVD release of Notorious, for example, he says that Alicia “is out of control — she has lost control.” These two phrases mean exactly the same thing — one or the other would have served perfectly well. He refers to the famous key in the film as “a prop — an object, if you want.” Yes, I will accept that a prop is an object, since a prop is always an object. It's sort of like saying, “a person — a human being, if you want.” This is a form of pretentious bloviation.

Casper misspeaks constantly in his commentary. He says that Alex's mother “yields a lot of power” in Alex's home, when he means that she wields a lot of power. Of a traveling shot close on Alicia and Devlin, Casper says it suggests that they are “floating on air, existing gravity.” I'm not even sure what he actually meant to say there — “resisting gravity”? Who knows?

Casper introduces the subject of Russian Constructivism and then goes on to refer to it more than once as Roman Contructivism, whatever that might be. Casper also misuses language freely. He says that German filmmakers “triumphed” the use of lighting as an expressive tool. He doesn't seem to know or care that “triumph” is an intransitive and never a transitive verb.

The professor is promiscuously careless about details as well. He refers to the German director “D. W. Pabst”. He says at one point that Alex is taller than Alicia, when he's just been talking about the significance of him being shorter. He says that in Hitchcock's films special effects are always in the service of technique, when he means always in the service of story or character.

Is there no editor or director present when Casper records his commentaries? Doesn't Casper, or someone, listen to them after they're recorded to catch mistakes and suggest retakes? Or is it the case that any old nonsense from the mouth of a man with a PhD is assumed to be authoritative?

Casper is not an idiot — he has many interesting things to say about the themes and strategies of Notorious — but he seems to feel no obligation whatsoever to present his analysis with even a modicum of intellectual rigor or discipline. If Hitchcock had had the same attitude about filmmaking that Casper has about film criticism, we wouldn't be watching Hitchcock's films today. Bloviating about them in such a scatter-brained way is a kind of insult to Hitchcock's professionalism.

Casper's poor language skills offer a terrifying insight into the modern academy, and modern academic standards in the area of film studies. Presumably Casper doesn't fear that his students will note, much less correct, his mangling of English, though some of them would undoubtedly be capable of doing so. They want good grades from him, after all. Presumably, as the occupant of an endowed chair at his university, probably a tenured position, he doesn't fear the criticism of his fellow professors or supervisors, who would have a very hard time removing him from his job. Perhaps they feel that since film is a visual medium, there's no need to speak about it in precise and correct language.

It's all very depressing. When a professor at a major American university can get away with such shoddy speech, it's no wonder that American institutions of higher learning are turning out graduates who are semi-literate, who not only speak but think sloppily about film, among other things.

LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MONSTERS

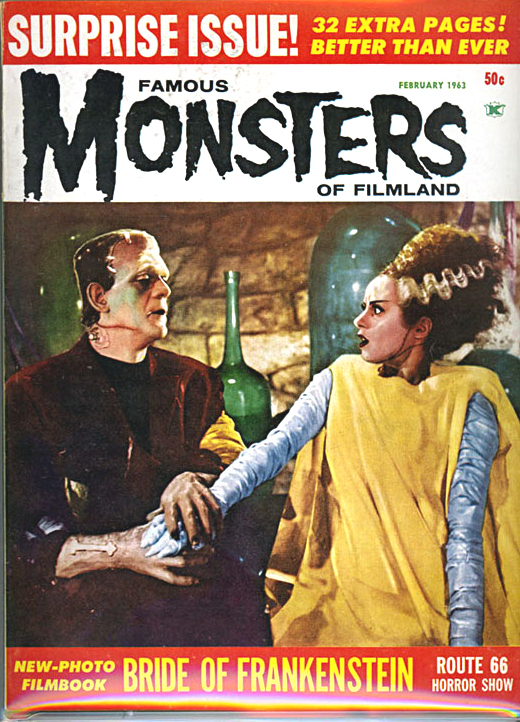

Forrest J. Ackerman died last Thursday, at the age of 92. For anyone who knew his name when they were 12 or 13 or 14, the news comes like the news of Queen Victoria's passing to residents of the British Empire in 1901. Ackerman presided over an empire of the imagination every bit as grand as Victoria's realm, and far more benign. He was the editor of Famous Monsters Of Filmland, the sci-fi and horror movie fan magazine around which a generation of buffs rallied during their formative years. It was a half-silly, half-serious publication devoted to the whole range and the whole history of fantasy on film. It helped to create and validate the community of kids who loved film of this sort, and gave them permission to take it seriously.

Famous Monsters was single-handedly responsible for focusing my own love of movies. It opened my eyes to silent film, because there were, after all, silent monster movies, and to other kinds of film. When I was 12 I started buying books about the history of movies just for their monster movie content and ended up enthralled by every kind of movie.

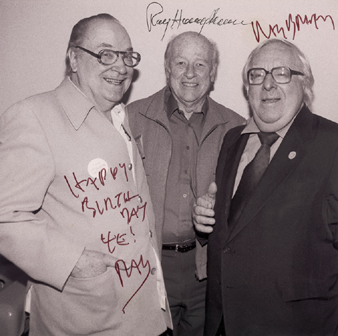

In seventh grade I met two fellow students who were secret fans of the magazine and introduced me to it — within months we were making our own 8mm monster movies. The three of us attended a science fiction convention in Washington, D. C. in the early Sixties where we actually met Forrest J. Ackerman (seen above, on the left, with Ray Harryhausen and Ray Bradbury.) He took us out to lunch. He took us and our interest in monster movies seriously. All of us, now in our fifties, are still fanatics of the kind of movies “Forry” loved.

Such stories could be repeated endlessly. Joe Dante, John Landis and Steven Spielberg were all fans of the magazine when they were kids. In later life, Spielberg autographed a

poster of Close Encounters of the Third Kind for Ackerman, writing, “A

generation of fantasy lovers thank you for raising us so well.”

And so we all do — now and forever.

A CALENDAR GIRL FOR DECEMBER

Hello, Santa . . .

[By Al Moore for Esquire, 1950]

POKER AND PORN

Last night Jae I played a little poker at Planet Hollywood, without much luck. At my table there was an extremely beautiful young woman, who played with a sense of fun and daring that was infectious. She had a fresh, innocent quality which was deceiving — she was always playing games, check-raising on draws for example, which is a bold move in a Las Vegas poker room, where people don't mind putting you all-in if they think you're trying to mess with them.

Afterwards Jae said he thought he recognized the woman, and suddenly realized where he'd seen her before — in a porn movie, where she performed sex acts for pay under the name of Jenni Lee. She's now “gone legit” and works as a model and professional poker player here in Las Vegas under her real name Stephanie Sadorra. She's just 26. Odd to move from porn to poker, where preserving your mystery is a key to winning. On the other hand, she did bet heavily and make people pay to see her cards, which is also a key to winning.

There are many cute female poker players here in Las Vegas who dress provocatively, showing lots of cleavage, and flirt ostentatiously to distract men and put them off their game. Ms. Sadorra wasn't that sort. She was dressed modestly and paid personal attention only to her boyfriend, who was playing at a nearby table. She looked more like the All-American girl in the photo at the head of this post (from her MySpace page) than like the provocative glamor girl gazing at herself in the mirror above.

Poker is a game where it's easy to leave your past behind in the intense concentration of excitement occasioned by each new fall of the cards. That's part of the intoxication of gambling, which, as Walter Benjamin once observed, obliterates time. I wonder if Ms. Sadorra looks at the faces of the people she's playing against and wonders if they've seen her in other contexts and think of her not as a pretty good poker player but as a very pretty ex-pornstar.

STUDIO SNOW

Next to real snow, there's nothing quite as lovely as studio snow in black-and-white films from Hollywood's Golden age.

shahn, at the ever-magical six martinis and the seventh art, is an aficionada of bogus blizzards on film and has posted some screen shots of my favorite ersatz snowfall in movies, from Swing Time.

If you live someplace warm, like the middle of the Mojave Desert, fix yourself some egg nog, light a fake fire, gaze through the window of your computer screen and enjoy the prop flakes in cozy comfort. Better still, give Swing Time another spin on your DVD player and watch the imaginary snowflakes fall on Fred and Ginger as they sing and dance their way into your heart one more time.

THE BOY WITH THE GOLDEN ARM

My friend Jae had a great run at the poker tables during the first couple of days of his visit here, and I made a little money, too. Then disaster struck, as it always does in poker, sooner or later. I can't go into the horrifying details, in case there are children reading this post, but Jae and I got deeply depressed and believed that we were unworthy of the game of Texas Hold-'em.

Then Jae got the bright idea of playing a tournament, which doesn't require risking much money but can pay off handsomely. We signed up for a noon contest at the Luxor. I had a panic attack before the first hand was dealt, but settled down and played well. I got some breaks, as you need to do in a tournament, and made the final table. I held on to finish fourth, which paid $125 against the $33 buy-in.

Jae didn't cash and felt even worse than before. We wandered over to the Monte Carlo poker room, where Jae lost some more money quickly, and I lost my Luxor winnings, and then some — but very slowly.

While I was doing this, Jae drifted around the casino like a lost soul. For some reason he put five dollars down on the pass line at a craps table and the dealer handed him the dice — the last shooter at the table had just crapped out and nobody was having any luck with the bones. When Jae established a point, the dealer told him to back up his bet with another five dollars. What happened next is already part of the legend of Las Vegas.

Jae started a magical roll that seemed to go on forever, making point after point after point. He could do no wrong with the dice. His initial ten-dollar investment kept growing. After a while a woman who was betting heavily on his rolls and winning big started placing bets in his name. He won even more. Jae eventually asked the dealer quietly if he should give the money for the bets back to the woman, now that he had so much.

“She's made five grand on your rolls,” the dealer whispered. “You don't owe her anything.” The woman, at the other end of the table, kept glancing tenderly at Jae, as though he were a long-lost love. A sudden windfall of five large can do that to a person.

When I finally busted out at the poker table and tracked Jae down he was up over $400 on his ten-dollar investment. I pulled him away from the table and urged him to cash in — his winnings more than covered all his poker losses since he hit town on this visit.

The dealers at the craps table had been looking at Jae in awe. “He made all that from a ten-dollar bet,” they'd say to anyone who passed the table, pointing at his chips. One dealer said, “I once made that much on a ten-dollar starting bet.” “Yeah,” said another dealer, “but we saw this run, so we know it really happened.”

Yes, it did. In the real-life fantasy land of Las Vegas.